SMITH BY JEFF SMITH

Title: ROLL MODELS

Civil disobedience tends to be a cyclical form of political expression. It only comes into flower every few years, even decades, and during the intermissions of its popularity, the great masses in the political middle tend to forget what an important tool it is.

Indeed, civil disobedience is the only legitimate means of effecting change on behalf of minority needs.

Mull it over:

• A minority with a valid and pressing need to see some public policy created or changed has the option of going to the polls along with everyone else . . . and losing. because it is, after all, a minority. Or:

• Its members could arm themselves and turn their minority cause into a guerilla war, which the majority would agree is hardly a legitimate solution. Or:

• They could employ the classic, nonviolent, Gandhian stratagem of civil disobedience.

Bingo.

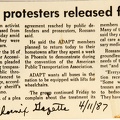

Which is why I endorse the protest staged recently by American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation (ADAPT). About 200 members of the Denver-based group, most of them in their primary means of transportation — wheelchairs— came here and raised hell a couple of weeks ago with the national convention of the American Public Transportation Association.

It was a classic sit-in. Gimps are good at that.

But it's been quite a while—a peaceful, soporific, almost brain-dead while—since the civil-rights movement and the Vietnam War era, when sit-ins, protest marches and similar styles of civil disobedience were at all common. And six years of Reagan, four of Carter and three of Ford have turned many of us into conservatives like Phoenix City Councilman Howard Adams, who sympathize the problems of certain minorities, but object to the only tactic they really can use to solve those problems.

Adams doesn't think cripples ought to be blocking restaurant and hotel entrances, impeding the comings and goings of conventioneers and blockading buses in order to make their point that most public transit is inaccessible to people in wheelchairs and those rendered nearly immobile by the need for canes and crutches.

Adams is not an unsympathetic man: He has both sympathy and empathy for the disabled. In case you didn't know it, Howard Adams is a gimp himself. He was crippled in a swimming accident twenty years ago.

And in case you think my characterizations mark me as a churl, know that I'm a gimp, too, coming on six years in a wheelchair after a motorcycle crash. (I got to be churlish independent of paralysis.)

So both Howard and I know something of the subject. I simply know more than he does on account of I'm smarter. So listen up: Neither Howard Adams nor Yr. Obdt. Svt. is a decent role model for anyone with ambitions of becoming disabled.

I am far too pretty and talented; Howard Adams is too powerful and prosperous.

It is way too easy for someone like Adams or me to say, Hey, why don't the rest of you gimps just get your own car or van, like me? Adams is a quadriplegic with a specially equipped van. It is his own rig, but he must get someone else to drive it for him. When he's on city business, or going to and from his Phoenix City Council office, the city provides the driver. I am a paraplegic, somewhat less handicapped than Adams, so I drive myself in a station wagon with hand controls.

Now you might think owning a car is virtually within the reach of anyone. Even the poorest hovel might have a Caddy parked outside. And you might say that since Smith and Adams manage so commendably, anybody can work and support a family, and get around to do [missing text here] unaffordable. Sensible people of limited means may own one old beater which one spouse takes to work, while the other rides the bus. Consider that even for Homo erectus, hoofing to the bus stop on hind feet in Hush Puppies and making the necessary connections to get from home in Phoenix to work in Tempe can be a major pain in the ass and add several hours to the workday. Now try it from a wheelchair.

Listen: I am about as adapted, chipper and successful a gimp as you're likely to meet, and I don't go to Circle K's anymore.

How familiar the ritual: You're driving home and you get a lech for a cold one. You hang a quick right, don't even shut off the engine, you're in and out in a flash, and buzzing nicely on your second beer before you've hit the next stoplight.

When you're in a wheelchair you don't do stuff like this anymore. It is simply too much bother. Even for a gimp like me, with great strong arms, catlike grace and his own automobile. I run wheelchair marathons, lift weights three times a week, have the cardiovascular system of a twelve-year-old, but I do not visit Circle K's. It takes too long, requires too much exertion, inflicts too much pain, and maybe there's no ramp.

Screw it.

If I had to call two days, or as much as a week in advance to arrange to have a special van pick me up—just to make a doctor's appointment or go buy - groceries—I don't know if I could cope. If Howard Adams had to plan his daily schedule around Phoenix bus schedules, which provide wheelchair service on only six of 54 bus routes, I wonder if he would be able to discharge his duties as a councilman.

I suppose he would, being the Type A he is. "I haven't showcased my activities," Adams told me, "but I am interested in this issue." Indeed, Adams has just been appointed to President Reagan's Architecture and Transportation . Compliance Board, which oversees enforcement of federal access regulation.

Adams said he thinks Phoenix is doing well on handicap access, but if he lived in, say, New York, he might be frustrated and angry. Then would he resort to civil disobedience? "Probably not," he said. "I'd work the [missing text here]

That might work for Howard Adams, - but not for all of Jerry's kids.

I've learned a lot of stuff about gimps since becoming one — stuff that contradicts most of what I thought I knew before. No two of us are alike. Being paralyzed doesn't mean blessed forgetfulness of the concerns of your formerly functional physiology.

You can experience constant pain from the paralyzed parts. You can have involuntary muscles spasms that make it impossible to sit still, and even more difficult to haul around those parts that would be tough enough to move if they just lay there like deadwood. You can run out of popcorn and have to get rest before the day is half done. You can spend two hours getting bathed and dressed to go out in public, only to get just out the door and find you've pissed your pants and have to go back and start all over.

Think about these things the next time you scoff at the demands of the disabled for better access to public transportation, for ramps at street corners, for rest rooms with doors wide enough for a wheelchair, for wider aisles in airplanes, elevators in two-story buildings.

Think what it means when a six-inch curb is as impassable a barrier as a prison wall. Not figuratively. In fact.

Think about these things and think about one thing further: Disability is a very Eighties fashion of affliction, tres chic you could say. With speed sports like sail-boarding, off-roading and even sidewalk surfing being so trendy, lots more of you hip, yuppie dudes and dudettes will be joining me on wheels in the very near future. Think of handicapped access as an investment in your own future.

Think of all this the next time you find yourself staring at the convenience market — the one with the cold can of beer— from across a lane of oncoming traffic, and you decide it's just too inconvenient to make a left-hand turn.

Believe thee me: You don't have a clue as to what inconvenience is.

- Created on

- Thursday 11 July 2013

- Posted on

- Monday 18 September 2017

- Tags

- ADAPT - American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, APTA - American Public Transit Association, civil disobedience, endorsement, gimps, protest, sit-in, Vice Mayor Adams, wheelchairs

- Albums

- Visits

- 1121

- Rating score

- no rate

- Rate this photo

0 comments