Chicago Tribune, Thursday May 14, 1992

[This article continues in ADAPT 712 but the entire text has been included here for easier reading.]

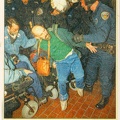

Photo by Eduardo Contreras: A man (Randy Horton) in a denim jacket kneels on the bottom step of an escalator with his arms spread from one handrail to the other. Someone stands on the escalator facing him. Behind him are a group of other protesters in wheelchairs filling the area. The group includes: Steve Verriden, San Antonio Funtes, Chris Hronis and others.

Caption reads: Randy Horton (on knees) blocks John Meagher on a State of Illinois Center escalator.

Title: Disabled protesters take hard line

by Christine Hawes and Rob Kawath

Rolling his wheelchair around the cavernous State of Illinois Center, shouting for his rights, Ken Heard recalled how he used to spend his days in a Syracuse, N.Y., nursing home where doctors controlled his life.

They would tell him when he could get up in the morning, when he could go to sleep, what he could eat. They would feed him pills, but they wouldn’t tell him what they were for. It was as if he had no mind of his own. “l saw people tied down in their beds, said Heard, who has severe cerebral palsy. "And I saw people die in there."

It took some time, a marriage that got him out of the nursing home and a raging desire for independence, but today Heard has regained the power to think for himself. He now earns his own income, rents and fumishes his own apartment and even takes vacations in Las Vegas.

His joumey to self-sufficiency began when he heard about an activist group now called American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today.

On Wednesday, about 200 ADAPT protesters in wheelchairs disrupted operations at the State of Illinois Center, 100 W. Randolph St., blocking exits and occasionally fighting with building patrons and workers as police stood by, arresting no one.

Elaborate security measures the state had put in place Monday to keep the 16-floor, 3,000-employee building functioning broke down while state and Chicago police squabbled over who was responsible for arresting protesters deemed to have gone too far.

But the scene of disabled men and women dragging themselves up escalators, surging into the building lobby and clutching the legs of people trying to walk past is just another picture in the well-publicized story of a group of vociferous activists savvy in street action.

“One of the strongest points of their civil disobedience is making themselves look as pathetic as possible,” said one Chicago-area official at an agency that has been a target of ADAPT. The official, who asked that his name be withheld, said, “They are excellent media users, and they are very successful at putting spotlights on issues that most people probably wouldn’t normally pay attention to.”

ADAPT has taken its dedication to a fever pitch, too fevered for some, and like many new protest `groups`—including the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT -UP) for gay rights, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) for animal rights and Earth First for the ecology—is using dramatic, sensational tactics for their cause, to allow any nursing home residents the ability to live on their own.

And though some may question their efforts, none can doubt they have impact. One woman who said she was grabbed, tripped and bitten during Wednesday’s melee confessed a few hours later, “I can’t help but feel guilty.”

During Heard’s 10-year stay in the nursing home, he met some ADAPT members from Denver and listened to them tell of how they took sledgehammers to Denver's street curbs as a way of objecting to inaccessible sidewalks.

Now Heard is a political organizer for ADAPT, in town with 350 other protesters. And though members are no longer taking sledgehammers to cement, they are steering wheelchairs into intersections, chaining themselves to buildings and crawling along dirty streets to get over curbs too high for wheelchairs.

For the past two years, ADAPT has been staging demonstrations every six months in support of reallocating one-fourth of the country’s Medicaid funds that now go to nursing homes to in-home health care, and to make it easier for disabled people like Heard to escape their “prisons.”

This week in Chicago, protests have played out at the quarters of everyone ADAPT perceives as the health-care power brokers: the federal Department of Health and Human Services, the American Medical Association and the offices of Gov. Jim Edgar.

ADAPT claims that having personal, in-home attendants for the disabled costs $900 a month less in state funds than keeping them in nursing homes and other institutions. Illinois officials say the difference is only $600.

But aside from financial concerns, ADAPT members say they’re fighting against inhumane restraint and abuse in nursing homes. Their strategy is to make the able-bodied feel as uncomfortable and limited as they themselves do—and to grab as much media time as possible.

Television cameras were there Wednesday when bands of wheelchair users mobbed workers trying to use an escalator in the State of Illinois Center.

And they were there Tuesday when protesters crawled out of their wheelchairs, across Grand Avenue and over foot-high curbs outside of the American Medical Association’s national headquarters.

“This makes us visible," said Jean Stewart, a 42-year-old novelist from New York, who has used a wheelchair since she lost her hip muscle because of a tumor about 17 years ago. “And it enables us to get our message across. It’s not a publicity stunt, it’s education.”

The group’s history is rife with attention-grabbing acts of protest after talks with officials were unsuccessful and full of what they feel is noteworthy success.

The end result of the Denver protests, said Wade Blank, a founding member of the group, was one of the most accessible cities for disabled people in this country.

Three years ago, a handful of ADAPT members were arrested for blocking a Chicago Transit Authority bus with their motorized wheelchairs. But two results of those efforts, they feel, were CTA purchase of buses with wheelchair lifts and even the passage of the federal Americans with Disabilities Act.

ADAPT members say they are disrupting business as usual because they are shut out of offices where politicians and association presidents could be sitting down to discuss the issue. And they are trapping members of the public to demonstrate how they feel trapped and restrained.

“For so long the issues surrounding disability have remained invisible,” said Stephanie Thomas, who lost her ability to walk when she was run over by a tractor 17 years ago. “So we have to do some extraordinary things to make people pay attention.”

Wednesday’s protest, which came after U.S. District Judge Milton Shadur refused to order a lessening of security measures at the state’s Chicago headquarters, left police and Department of Central Management Services security officers snapping only at each other, even after the protest turned ugly.

“I have to get to an appointment!" yelled one middle-age man as he wrestled on the ground with two protesters who had grabbed his legs and, in the process, had been pulled out of their wheelchairs.

“This is what it feels like to be trapped in a nursing home!” yelled one protester.

The man finally struggled free and hustled out of the building while Chicago and Central Management Services police watched from only a few feet away.

“We’re sorely disappointed with the Chicago Police Department,” said Central Management Services Director Stephen Schnorf. “Certainly they provided better protection to the other buildings where there were protests this week.”

But Chicago Police Cmdr. Michael Malone said the state was in control and his officers were just there to back them up. He said the state was misrepresenting the agreement between the two departments.

And all that consternation was caused by a group that claims to be loosely organized and barely funded ADAPT, which has about 5,000 members nationwide, has very little formal correspondence, aside from a newspaper called Incitement and a rare memo, Blank said members keep in touch through word of mouth more than anything, and most of them support their travels through small fundraisers.

But though the group says most of its day-to-day procedures are hardly sophisticated, ADAPT leaders are extremely skilled in using the media, say some who have watched the group’s protests first-hand.

Sonya Snyder, public relations director at a Florida hotel where ADAPT demonstrated against the American Health Care Association last October, said the protesters only became rambunctious when television cameras appeared.

“For most of the time, the police and the protesters would share sandwiches,” Snyder said. “But when the media came, down went the sandwiches and up went the protest.”

And Janice Wolfe, a spokeswoman for the health care association, said the group’s efforts are “frustrating and misdirected. Their efforts could be better spent on individuals who are in power to do something.”

ADAPT members view their protests as grand displays of strength, not pitiful appeals. They speak of their demonstration plans as though they are plotting battle strategy, using words like “identified enemy,” “privileged information” and "top secret."

They pattern their protests after the civil rights demonstrations of the 1960s and compare themselves to the black leaders of that era “This is just like Martin Luther King,” ADAPT member Bernard Baker from Atlanta “We’re fired up, and we can’t take it anymore."

- Author

- Chicago Tribune/ Christine Hawes and Rob Kawath

- Created on

- Friday 12 July 2013

- Posted on

- Thursday 29 November 2018

- Tags

- ACT UP, ADAPT - American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today, AMA - American Medical Association, Bernard Baker, blocking entrances, blocking escalators, choice, Chris Hronis, civil rights, community services less expensive, cost, CTA - Chicago Transit Authority, Denver, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Earthfirst, Governor Edgar, grabbing, HHS - Health and Human Services, Incitement, Jean Stewart, Ken Heard, law enforcement battles, life in a nursing home, media, Medicaid, nursing homes, Orlando, PETA, Randy Horton, redirect 25%, San Antonio Fuentes, sledgehammer, Sonya Schneider, State of Illinois Center, Stephanie Thomas, Steve Verriden, tactics, tied to bed, Wade Blank

- Albums

- Visits

- 5009

- Rating score

- no rate

- Rate this photo

0 comments