- Ngôn ngữAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Trang chủ / Đề mục / Thẻ march + Governor Richard Lamm

+ Governor Richard Lamm + APTA suit

+ APTA suit 2

2

![ADAPT (208) (12184 visits) The San Diego Union March 2, 1986, page A3

The West [section of newspaper]

Drawing of Mr Louv'... ADAPT (208)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/08/20160108130058-7eec73bc-me.jpg) ADAPT (208)

ADAPT (208)

The San Diego Union March 2, 1986, page A3 The West [section of newspaper] Drawing of Mr Louv's head: White, youngish, short dark hair parted on side and glasses. [Headline] Transportation news for handicapped ‘a nightmare’ By Richard Louv The WHEELCHAIRS are rolling. On Jan. 16, in Dallas, handicapped demonstrators decrying "taxation without transportation," chained themselves to public buses, forcing traffic detours for nearly six hours. In downtown Los Angeles, last Oct 7, more than 200 people in wheelchairs rolled down the middle of Wilshire Boulevard to protest the policies of the American Public Transit Association. In San Antonio last April, 60 handicapped people staged a four-hour protest at the city's public transit offices, causing 90 nervous bus company employees to lock themselves in their offices for an hour until the transit association agreed to meet the demonstrators. And on Feb. 13, Houston police arrested eight demonstrators in wheelchairs and carted them off to jail in lift-equipped police vans. Their sentencing is tomorrow. and a representative of the Denver-based American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit told me that if the protesters “spend weeks in jail, it will be like when Martin Luther King went to jail in Birmingham. People will realize we're not just out playing in the street" What's going on here? The disabled~rights movement isn't new, of course. It began in Berkeley in the late 60s, and ultimately resulted in a government shift from segregating handicapped people to "mainstreaming" them into the rest of society. According to Cyndi Jones, publisher of San Diego-based Mainstream, a national magazine for the “able-disabled," some of the first generation leaders "got co-opted by government jobs, and frustration for the rest of us has been growing." A raft of laws were passed during the 1970s, but the laws. says Jones. still haven't been fully implemented. “The Rehabilitation Act promised disabled people equal access to public transportation facilities and education and employment. In education. the news has been good, but transportation is a nightmare." IN 1981, CONTENDING THAT putting lifts on buses was an unrealistic expense, the American Public Transit Association sued the federal government and won. Most cities stopped deploying the mechanical lifts that enable people using wheelchairs, walkers and crutches to board buses. The favored transportation method, at least among municipal officials, became small, subsidized "dial-a-ride" vans. "That's like putting us back in segregated schools," says Jones. The disability groups have a number of other complaints, some of them affecting many more people — lack of housing, attended care, airplane facilities. But what it has come down to is the symbol of lifts. While some disabled people are satisfied with the dial-a-ride approach, Jones says "taking a van service can cost you $60 to get to work and back. You have to call and reserve a ride — sometimes days in advance, and these services can't always guarantee a specific arrival time or even take you home. As a result, a lot of us can't afford to work, or we just stay home." California still requires lifts on all new buses, but Jones contends that the transit companies can develop some creative delaying tactics. Roger Snoble, the San Diego Transit Corp.'s general manager, agrees with her. "Some cities," he says, "don't care whether the lifts work once they put them on. They just let them go, and then say the lifts don't work." Jones, by the way, gives relatively high marks to San Diego's bus system; not so to the trolley. which she calls “miserable for handicapped people." As she sees it, a new generation of leaders in the disabled~rights movement is just now coming of age. They have some powerful opponents —— with some powerful statistics. Jim Mills, chairman of the Metropolitan Transit Development Board, has pointed out that in Los Angeles the average cost per ride of the various dial-a-ride systems “is $6.22, while the costs associated with a one-way trip on a bus for a person in a wheelchair is $300." And in a recent interview, Colorado Gov. Richard Lamm told me, "I think it is a myopic use of capital to try to put a lift on every bus in America. It costs the St. Louis bus system $700 per ride to maintain lifts." But Roger Snoble says it costs San Diego far less — $166 per ride (as of a year ago, "the last time we checked, and we expect the cost to continue to decline because of dramatically improving technology." And when I mentioned Lamm's figures to Dennis Cannon, the chief federal watchdog for the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Transit Compliance Board, he said, “Lamm's figures are at least six or seven years old, and wrong. These same figures get used a lot by lift opponents, but they're based on one of the very first generations of lifts, which were poorly administered and poorly installed by St. Louis during one the worst winters in Missouri history." He points out that Seattle, with one of the best bus systems in the nation, has managed to get the per-ride costs down to $5 or $10, depending on the amount of ridership. And Denver has decreased its lift failures from 25 a day to five within the last year. WITH ADVANCES LIKE this, combined with the increasing demands from disabled groups, a number of cities have decided that the lifts make economic sense — maybe not in this decade, but soon. "What's about to hit is a wave of people who expect to have equal access, the children of the mainstreaming movement," says Jones. During the past decade, government and society encouraged disabled people to work independently, and now that generation will be at bus stops and trolley stations all over the country, waiting to go to work. With them will be aging baby boomers, a giant crop of potentially disabled seniors. "Only one~third of the disabled population is employed. but two-thirds of disabled people are not receiving any kind of benefits," says Andrea Farbman, a spokeswoman for the National Council on the Handicapped. “Still. we're spending huge amounts of money keeping people unemployed — $60 billion dollars a year, but only $2 billion going to rehabilitation and special education." One rough estimate, says Farbman, is that 200,000 handicapped people would enter the work force if the travel barriers were eliminated. adding as much as $1 billion in annual earnings to the economy. The tragedy is this: While politicians wrangle over the costs of bus lifts, nobody has studied how much money could be saved in government benefits, and how much could be gained through taxes and added national productivity if more handicapped Americans were employed. ADAPT (200)

ADAPT (200)

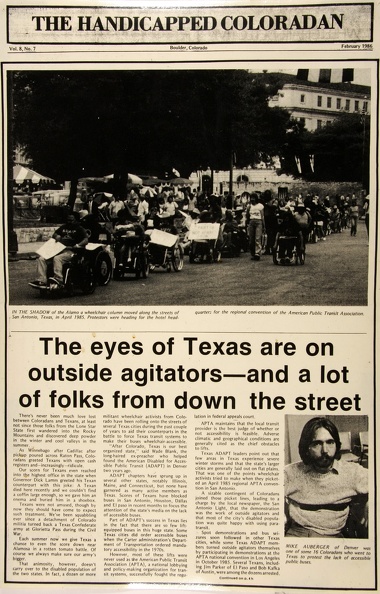

The Handicapped Coloradan, vol.8, no.7, Boulder, CO February 1986 (This article is continued in ADAPT 198 but the entire article is included here for ease of reading.) PHOTO 1: Along a street a large line of people in wheelchairs and others move past a shady park with vendors with small umbrellas over their stands. Several of the protesters carry placards in their laps, one of which reads: A PART OF NOT APART FROM. Faces are too dark to tell who is in the line. Caption reads: In the shadow of the Alamo a wheelchair column moved along the streets of San Antonio, Texas in April 1985. Protestors were heading for the hotel headquarters for the regional convention of the American Public Transit Association. PHOTO 2: Mike Auberger, with his mustache, trimmed beard and shoulder length hair looks at the camera with his intense eyes. Wearing a light colored sweater and shirt with a collar, he sits in his wheelchair which is mostly visible because of his chest strap. Caption reads: Mike Auberger of Denver was one of some 16 Coloradans who went to Texas to protest the lack of accessible public buses. [Headline] The eyes of Texas are on outside agitators -- and a lot of folks from down the street There's never been much love lost between Coloradans and Texans, at least not since those folks from the Lone Star State first wandered into the Rocky Mountains and discovered deep powder in the winter and cool valleys in the summer. As Winnebago after Cadillac after pickup poured across Raton Pass, Coloradans greeted Texans with open cash registers and - increasingly -- ridicule. Our scorn for Texans even reached into the highest office in the state when Governor Dick Lamm greeted his Texan counterpart with this joke: A Texan died here recently and we couldn't find a coffin large enough, so we gave him an enema and buried him in a shoebox. Texans were not amused, though by now they should have come to expect such treatment. We've been squabbling ever since a detachment of Colorado militia turned back a Texas Confederate army at Glorietta Pass during the Civil War. Each summer now we give Texas a chance to even the score down near Alamosa in a rotten tomato battle. OF course we always make sure our army's bigger. That animosity, however, doesn't carry over to the disabled population of the two states. In fact, a dozen or more militant wheelchair activists from Colorado have been rolling onto the streets of several Texas cities during the past couple of years to aid their counterparts in the battle to force Texas transit systems to make their buses wheelchair-accessible. "After Colorado, Texas is out best organized state," Wade Blank, the long haired ex-preacher who helped found American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) in Denver two years ago. ADAPT chapters have sprung up in several other states, notably Illinois, Maine, and Connecticut, but none have garnered as many active members as Texas. Scores of Texans have blocked buses in San Antonio, Houston, Dallas and El Paso in recent months to focus the attention of the state's media on the lack of accessible buses. Part of ADAPT's success in Texas lies in the fact that there are so few lift-equipped buses in this huge state. Some Texas cities did order accessible buses when the Carter administration's Department of Transportation ordered mandatory accessibility in the 1970s. However, most of these lifts were never used as the American Public Transit Association (APTA), a national lobbying and policy making organization for transit systems, successfully fought the regulation in federal appeals court. APTA maintains that the local transit provider is the best judge of whether or not accessibility is feasible. Adverse climatic and geographical conditions are generally cited as the chief obstacles to lifts. Texas ADAPT leaders point out that few areas in Texas experience severe winter storms and that the state's larger cities are generally laid out on flat plains. That was one of the points wheelchair activist tried to make when they picketed in April 1985 regional APTA convention in San Antonio. A sizable contingent of Coloradans joined those picket lines, leading to a charge by the local newspaper, the San Antonio Light, that the demonstration was the work of outside agitators and that most of the city's disabled population was quite happy with using paratransit. Spot demonstrations and bus seizures soon followed in other Texas cities, while some Texas ADAPT members turned outside agitators themselves by participating in demonstrations at the APTA national convention in Los Angeles in October 1985. Several Texans including Jim Parker of El Paso and Bob Kafka of Austin, were among The dozens arrested. Supporters of lifts point to cities like Seattle and Denver where most of the buses are accessible -- and increasingly free of breakdowns. Denver's Regional Transportation District (RTD) maintenance crew made a few simple changes in some of their lift systems and managed to operate experimental buses without a single breakdown. ADAPT argues that some transit providers have deliberately sabotaged their lift systems to justify removing them. Opponents of lifts argue that paratransit--usually vans that pick riders up at their residences -- is more cost effective. Supporters point to Seattle where the cost per ride on mainline buses is less than $15 a trip, which compares very favorably with the best deals offered by paratransit systems. Convenience is a major factor too, according to Mike Auberger of ADAPT-Denver, who points out that most paratransit systems require two days' advance notice and users might have to travel all day just to keep a 15 minute dental appointment. "Me, I like being able to roll down to the corner bus stop," Auberger said. ADAPT grew out of coalition of Denver disabled groups who were successful in battling RTD over wheelchair lifts. Protestors seized buses and chained themselves to railings at RTD headquarters before the battle was won. Two years ago they went national when their arch foe, APTA, held its national convention in Denver, APTA refused to allow ADAPT to present a resolution to the convention calling for mandatory accessibility until pressure was brought to bear by Denver Mayor Federico Pena, a pro-lift advocate. APTA declined, however, to vote on the issue, and ADAPT picketed the group's 1984 national convention in Washington, DC, in October. Twenty-four protestors were arrested during the demonstration, including Parker. Parker, who was joined in Washington by four other Texans, isn't through with APTA yet. When that group holds its Western Regional Convention in San Antonio April 20, Parker said they can expect almost as many demonstrators as went to Washington. "I can't think of any place in Texas where it (public transportation for the disabled) is as good as it is here in Denver -- in fact it's poor everywhere here. Dallas just decided to buy 200 or 300 new buses without lifts." The situation isn't any better in his home city of El Paso, according to Parker. "It's very poor here," he said. "There are 30 city cruisers here with lifts but the city has shown no desire to use them." Parker thinks too many people in wheelchairs are too passive. "They're not used to pushing people, but we're starting to see some changes." However, Parker points out that Texas is a very conservative state and people -- including the disabled -- are slow to change. People wishing to participate in the San Antonio demonstration should call Parker (915-564-0544) for further information. PHOTO: Two bearded, bare chested wheelchair activists (Jim Parker, and [I think] Mike Auberger) are in the foreground. Parker, his shoulder length hair tied back with a bandana, sits with his foot up on his opposite knee, hands in his fingerless gloves. The two are facing away from the camera and talking with another man who is kneeling down beside them looking up at them. Caption reads: Jim Parker (center) of ADAPT-El Paso meets with a newsman during a picket of McDonald's. Many disabled persons objected to the fast food chain's refusal to immediately retrofit all of its restaurants so that they would be accessible to wheelchair patrons. Parker is currently involved in helping organize a demonstration at the Western Regional Convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) in San Antonio Oct. 20 - 24 [sic].