- Rindošanas secībaNoklusējums

Foto nosaukums, A → Z

Foto nosaukums, Z → A

Izveides datums jaunais → vecais

Izveides datums, vecais → jaunais

Publicēšanas datums, jaunais → vecais

Publicēšanas datums, vecais → jaunais

Novērtējums, augsts → zems

✔ Novērtējums, zems → augsts

Apmeklējums, augsts → zems

Apmeklējums, zems → augsts - ValodaAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Sākums / Albūmi / Tagi civil disobedience + separate but equal

+ separate but equal 3

3

![ADAPT (413) (58897 visits) [This artlice continues in ADAPT 412, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.]

P... ADAPT (413)](_data/i/upload/2017/12/20/20171220190649-0fd5f489-la.jpg) ADAPT (413)

ADAPT (413)

[This artlice continues in ADAPT 412, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] PHOTO 1: A group of protesters in wheelchairs, in a rough line, head down the street toward the camera. In front and to one side a policeman on a motorcycle/trike. Caption: ADAPT demonstrators, with police escort, on their way from the Arch to Union Station, via Market Street PHOTO 2: Four protesters in wheelchairs block a flight of stairs in a lobby type area as people walk by. From left to right they are Ryan Duncan, Heather Blank, unknown protester, and Wayne Spahn. Caption: Demonstrators blocked access to stairways in Union Station, trying to force a confrontation with APTA officials. [No Title or author or publication given for this article on the clipping. It does not appear be the start of the article.] "They bill it as door to door service, but it does crazy things like, if you want to go from west county to the city, it will pick you up but leave you at the city-county line." Bi-State plans to expand the service in December by adding 11 lift-equipped vans and extending the service into the city. The system will also extend its hours of operation, to 6 a.m. to 7 p m. Its use in the city limits will be limited to disabled passengers, Plesko says, and, with the extended hours, disabled workers will be able to use the service to get to their jobs. While some other cities are making similar (or greater) progress — San Francisco, for one, has lifts on every one of its buses — things are still moving too slowly for the members of ADAPT. And they blame the slow pace on APTA. (ADAPT members who came to St. Louis this week stressed that they were here because of their quarrel with APTA and were not here to demonstrate against Bi-State. They said they approved of the plans Bi-State had made for the achievement of 100 percent accessibility, but nonetheless questioned the slow pace at which that was occurring.) The fight between ADAPT and APTA has its roots in the 1970s. During the Carter administration, the Department of Transportation (DOT) issued rules requiring transit systems to have at least half of their buses equipped with wheelchair lifts. Those regulatioms came out of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, a landmark federal law that many in the disabled community point to as being equivalent to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But APTA filed suit against DOT for its regulations and a federal court upheld APTA's argument for "local option," that is, allowing individual transit authorities to decide how they would comply with the spirit of the regulation requiring adequate accessible transportation for the disabled. Says APTA's Engelken, "These decisions are best made locally, because the local transit systems understand the needs of their passengers. For example, it would not be feasible to have a transit system for the disabled based on 100 percent lift-equipped buses in Fargo, North Dakota, because in the winter it would be almost impossible for someone in a wheel chair to get to a bus stop and wait for a bus. Able-bodied people have enough trouble (there)." Says Bob Kafka, another ADAPT leader, "(That) is one of the arguments people use for not providing transportation. They say, 'People in a motorized wheelchair can't get there, so why provide (accessible buses)?' But do you know what a person in a motorized wheelchair has to do to get to the bus stop? He has to hit a joystick. Little old ladies cleaning people's homes for years, with fallen arches, and having to carry shopping bags, no one has ever said we need special transit for them. But a disabled person who has to hit a joystick to operate his wheelchair, we need special transportation for them because it’s too cold, too snowy, too hilly, too wet, too this. "It's like were going to break, were going to fall apart." ADAPT sees APTA's insistence on local option as an attempt by the group to foster so-called "separate-but-equal” transportation systems. They say that APTA is attempting to segregate transit systems; keeping disabled passengers out of the mainstream system. ADAPT was formed in 1982 in Denver by Auberger and a handful of other members of that city's disabled community. It was put together because APTA had scheduled a convention for Denver and APTA's resistance to 100 percent accessible main-line public transportation for the disabled made the trade organization the moral equivalent of "the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazi party" for disabled Americans, Kafka says. Thirty demonstrators showed up at the first protest, and there have been eight subsequent protests, all at APTA regional or national conferences. The demonstrators model their actions after the non-violent civil rights activists of the 1960s. They block access to buses: they block access to the APTA convention sites. Some, including Auberger, chain themselves to buses or to doorways. The aim is arrest and the accompanying media attention. Auberger has been arrested at least 30 times by his own count, including this past Sunday at the Omni Hotel. ADAPT's militant tactics have drawn criticism from several corners, including others who work in the disabled community. "While we agree with the goals and-objectives of accessibility for disabled persons, we don't agree with the tactics of civil disobedience or confrontation as a means to achieve those objectives," says Ginny Weber, assistant to Deborah Phillips, the commissioner of the city's Office on the Disabled. "There are other ways to get things done," she says. "You can go through the legislative process. You can conduct public awareness campaigns. Over the last 10 years, some progress has been made. To change conditions that have been in existence for a long time takes a while. You have to just stay in there' and keep working towards it." Sheldon Caldwell, executive director of the St. Louis Society for Crippled Children, agrees. "I don't think it pleads our case well to have a group with a disruptive militant attitude. This is my personal opinion: I haven't polled my staff on this, but I don't think disruption is ever the way to go about it. But others are not as harsh in their judgment. "I take a different position (from those who criticize ADAPT)," says Paraquad's Tuscher. "I have the point of view that there are many ways to get from where we are to where we want to go. We're more likely to use negotiation, legislative action, legal action, public relations campaigns. Confrontation is not one of our methods, but I don't think it's my place to judge (ADAPT). Let history judge: let history prove whose method is the right one." About the criticism from within the disabled community, ADAPT's Kafka says, "Those who are in power are not going to give it up to you willingly. Without the push of civil disobedience, even the Civil Rights Act would never have come about." Says Auberger, "(Negotiation and public relations campaigns) delay the justice. It's not perceived as delaying justice, but it is. They are doing harm to their disabled brothers and sisters by saying, 'I don't support their tactics, but I do agree with their position.— Because other groups for the disabled receive so much financial support from corporations, they are less willing to be as direct in their demands as is ADAPT, he says. "They will eat a lot of garbage just to get half the loaf. "If you're going to change things, you have to get rid of the notion right away that you are going to be someone's friend," he says. "Be-cause someone is going to want something different than you do. The city of St. Louis and I will never be friends. The police and I will never be friends, but I won't lose any sleep over it. I know when I leave here, people will be talking about this issue in a way it hasn't been talked about before and something might change. "You look at demonstrators in history. Go back to the civil rights movement. The blacks who demonstrated weren't seen as 'nice.' If you go back further, to the women's suffrage movement, those women who wanted the right to vote weren't seen as mom and apple pie. But typically people who have been vocal about their rights are never perceived as being nice." PHOTO 1: Two men, one a plain clothes policeman and the other the bus driver, load a man in a scooter onto an accessible bus as several other people in suits and uniforms look on. Caption: St. Louts police arrested 41 demonstrators at the Sunday protest by ADAPT at the Omni. PHOTO 2: A man (Mike Auberger) with his hair pulled back tightly, wearing glasses, a beard and an ADAPT no steps T-shirt, sits in a long hall with bars of light on the walls and ceiling. He holds up his hands, fingers permanently folded at the first joint, guesturing as he speaks. He has a chest strap to hold him in his motorized wheelchair. Caption: Mike Auberger, one of the founders of ADAPT ADAPT (148)

ADAPT (148)

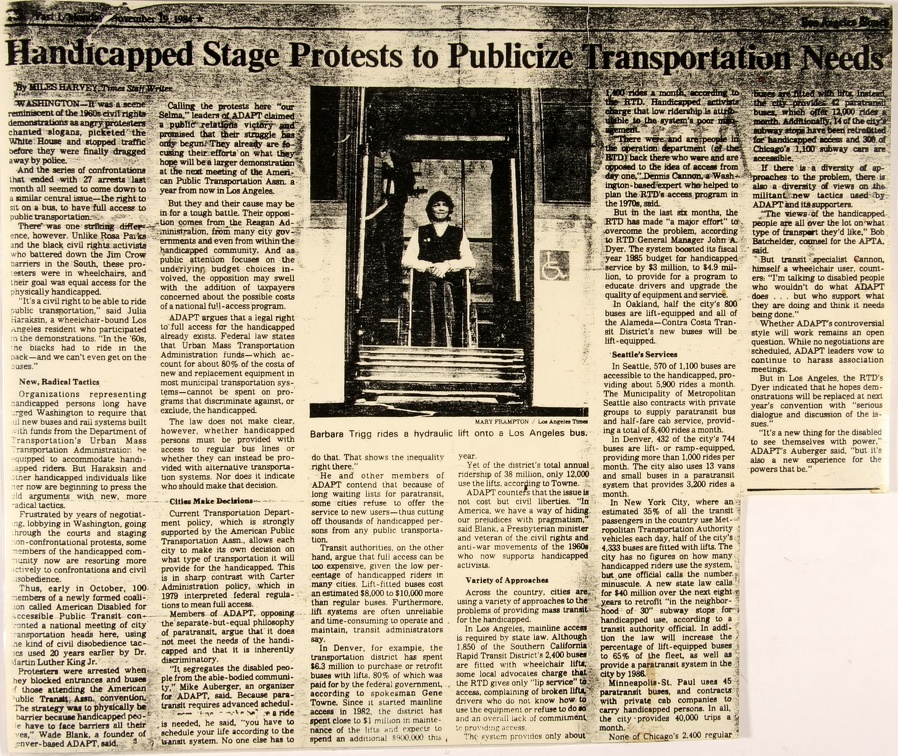

Name of newspaper illegible Los Angeles Times? November 19,1984 Handicapped Stage Protests to Publicize Transportation Needs by Miles Harvey, Times Staff Writer PHOTO: Mary Frampton / Los Angeles Times A tidy looking woman in pants and a vest, with a slight smile on her face, sits in a manual wheelchair on a bus. She is sitting in the accessible doorway, the access symbol visible on the side of the doorway. Below and beneath her is a metal panel, like the barrier on some lifts that keeps the person from rolling off the front of the lift. Caption reads: Barbara Trigg rides a hydraulic lift onto a Los Angeles bus. Article reads: Washington -- It was a scene reminiscent of the 1960s civil rights demonstrations as angry protesters chanted slogans, picketed the White House and stopped traffic before they were finally dragged away by police. And the series of confrontations that ended with 27 arrests last month seemed to come down to a similar central issue— the right to sit on a bus, to have full access to public transportation. There was one striking difference, however. Unlike Rosa Parks and the black civil rights activist who battered down the Jim Crow barriers in the South, these protesters were in wheelchairs, and their goal was equal access for the physically handicapped. “It's a civil right to be able to ride public transportation," said Julia Haraksin, a wheelchair-bound Los Angeles resident who participated in the demonstrations. “In the ‘60s, the blacks had to ride in the back—and we can't even get on the buses." New, Radical Tactics Organizations representing handicapped persons long have urged Washington to require that new buses and rail systems built with funds from the Department of Transportation's Urban Mass Transportation Administration be equipped to accommodate handicapped riders. But Haraksin and other handicapped individuals like her now are beginning to press the old arguments with new, more radical tactics. Frustrated by years of negotiating, lobbying in Washington, going through the courts and staging non-confrontational protests, some members of the handicapped community now are resorting more actively to confrontations and civil disobedience. Thus, early in October, 100 members of a newly formed coalition called American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit confronted a national meeting of city transportation heads here, using the kind of civil disobedience tactics used 30 years earlier by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Protesters were arrested when they blocked entrances and buses of those attending the American Public Transit Assn. convention. The strategy was to physically be a barrier because handicapped people have to face barriers all their lives," Wade Blank, a founder of Denver-based ADAPT said. Calling the protests here " Selma," leaders of ADAPT claimed victory and promised that their struggle has only begun. They already are focusing their efforts on what they hope will be a larger demonstration at the next meeting of the American Public Transportation Assn. a year from now in Los Angeles. But they and their cause may be in for a tough battle. Their opposition comes from the Reagan Administration, from many city governments and even from within the handicapped community. And as public attention focuses on the underlying budget choices involved, the opposition may swell with the addition of taxpayers concerned about the possible costs of a national full-access program. ADAPT argues that a legal right to full access for the handicapped already exists. Federal law states that Urban Mass Transportation Administration funds — which account for about 80% of the costs of new and replacement equipment in most municipal transportation systems—cannot be spent on programs that discriminate against, or exclude, the handicapped. The law does not make clear, however, whether handicapped persons must be provided with access to regular bus lines or whether they can instead be provided with alternative transportation systems. Nor does it indicate who should make that decision. Cities Make Decisions Current Transportation Department policy, which is strongly supported by the American Public Transportation Assn., allows each city to make its own decision on what type of transportation it will provide for the handicapped. This is in sharp contrast with Carter Administration policy, which in 1979 interpreted federal regulation to mean full access. Members of ADAPT, opposing the separate-but-equal philosophy of paratransit argue that it does not meet the needs of the handicapped and that it is inherently discriminatory. "It segregates the disabled people from the able-bodied community," Mike Auberger, an organizer for ADAPT, said. Because paratrasit requires advanced scheduling [unreadable] a ride is needed, he said, “you have to schedule your life according to the system. No one else has to do that. That shows the inequality right there." He and other members of ADAPT contend that because of long waiting lists for paratransit, some cities refuse to offer the service to new users - thus cutting off thousands of handicapped persons from any public transportation. Transit authorities, on the other hand, argue that full access can be too expensive, given the low percentage of handicapped riders in many cities. Lift-fitted buses cost an estimated $8,000 to $10,000 more than regular buses. Furthermore, lift systems are often unreliable and time-consuming to operate and maintain, transit administrators say. In Denver, for example, the transportation district has spent $63 million to purchase or retrofit buses with lifts. 80% of which was paid for by the federal government, according to spokesman Gene Towne. Since it started mainline access in 1982, the district has spent close to $1 million in maintenance of the lifts and expects to spend an additional $900,000 this year. Yet of the district's total annual ridership of 38 million, only 12,000 use the lifts, according to Towne. ADAPT counters that the issue is not cost but civil liberties. “In America we have a way of hiding, our prejudices with pragmatism," said Blank, a Presbyterian minister and veteran of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s who now supports handicapped activists. Variety of Approaches Across the country, cities are using a variety of approaches to the problems of providing mass transit for the handicapped. In Los Angeles, mainline access is required by state law. Although 1,850 of the Southern California Rapid Transit District‘s 2,400 buses are fitted with wheelchair lifts some local advocates charge that the RTD gives only "lip service" to access, complaining of broken lifts, drivers who do not know how to use the equipment or refuse to do so and an overall lack of commitment to providing access. The system provides only about 1,400 rides a month according to the RTD. Handicapped activists charge that the low ridership is attributable to the system's poor management. There were and are people in the operation department (of the RTD) back there who were and are opposed to the idea of access from day one," Dennis Cannon, a Washington-based expert who helped to plan the RTD's access program in the 1970s said. But in the last six months, the RTD has made "a major effort" to overcome the problem, according to RTD General Manager John A. Dyer. The system boosted its fiscal year 1985 budget for handicapped service by $3 million, to $4.9 million, to provide for a program to educate drivers and upgrade the quality of equipment and service. In Oakland, half the city's 800 buses are lift-equipped and all of the Alameda — Contra Costa Transit District's new buses will be lift-equipped. Seattle’s Services In Seattle, 570 of 1,100 buses are accessible to the handicapped, providing about 5,900 rides a month. The Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle also contracts with private groups to supply paratransit bus and half-fare cab service, providing a total of 8,400 rides a month in Denver. 432 of the city's 744 buses are lift- or ramp-equipped, providing more than 1,000 rides per month. The city also uses 13 vans and small buses in a paratransit system that provides 3,200 rides a month. In New York City, where an estimated 35% of all the transit passengers in the country use Metropolitan Transportation Authority vehicles each day. half of the city's 4,333 buses are fitted with lifts. The city has no figures on how many handicapped riders use the system, but one official calls the number minuscule. A new state law calls for $40 million over the next eight years to retrofit “in the neighborhood of 30" subway stops for handicapped use, according to a transit authority official. In addition the law will increase the percentage of lift-equipped buses to 65% of the fleet, as well as provide a paratransit system in the city by 1988. Minneapolis-St. Paul uses 45 paratransit buses and contracts with private cab companies to carry handicapped persons in all, the city provides 40.000 trips a month. None of Chicago's 2.400 regular buses are fitted with lifts. Instead the city provides 42 paratransit buses, which offer 12,000 rides a month. Additionally, 14 of the city's subway stops have been retrofitted for handicapped access and 300 of Chicago's 1,100 subway cars are accessible. If there is a diversity of approaches to the problem, there is also a diversity of views on the militant new tactics used by ADAPT and its supporters. The views of the handicapped people are all over the lot on what type of transport they'd like," Bob Batchelder, counsel for the APTA, said. But transit specialist Cannon, himself a wheelchair user, counters: “I'm talking to disabled people who wouldn't do what ADAPT does ... but who support what they are doing and think it needs being done." Whether ADAPT's controversial style will work remains an open question. While no negotiations are scheduled, ADAPT leaders vow to continue to harass association meetings. But in Los Angeles, the RTD's Dyer indicated that he hopes demonstrations will be replaced at next year's convention with “serious dialogue and discussion of the issues." "It’s a new thing for the disabled to see themselves with power," ADAPT's Auberger said, "but it's also a new experience for the powers that be." ADAPT (180)

ADAPT (180)

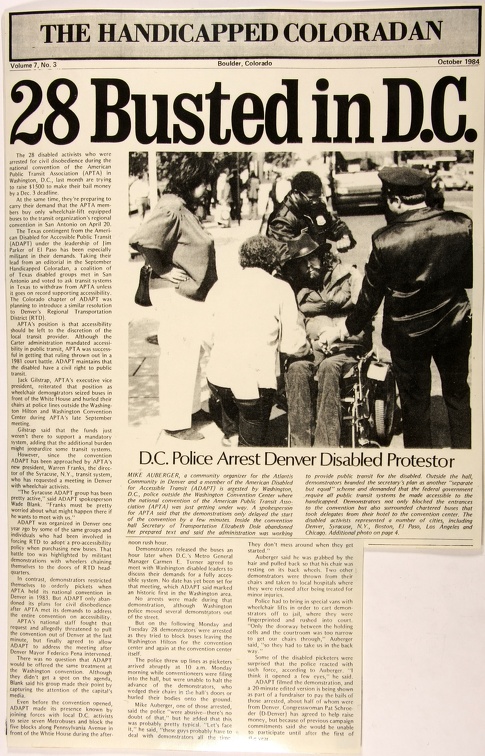

THE HANDICAPPED COLORADAN Volume 7, No. 3 Boulder, Colorado October 1984 PHOTO: A man in a leather brimmed hat, long hair beard and moustache down vest and jeans, seated in a motorized wheelchair (Mike Auberger), leans to his right as he is surrounded by abled bodied people. Back to the camera, a man plain clothes is partially in front of him, papers sticking out from his back pocket. A uniformed officer is also back to the camera and is holding Mike's arm which in front of Mike. A second uniformed officer is doing something behind Mike's back while a woman stands up on the sidewalk to his side watching with her hands on her hips. (She was an organizer with National Training and Information Center and was assisting with the Access Institute.) cation reads: D.C. Police Arrest Denver Disabled Protestor MIKE AUBERGER, a community organizer for the Atlantis Community in Denver and a member of the American Disabled for Accessible Transit (ADAPT) is arrested by Washington, D.C., police outside the Washington Convention Center where the national convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) was just getting under way. A spokesperson for APTA said that the demonstrations only delayed the start of the convention by a few minutes. Inside the convention hall Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole abandoned her prepared text and said the administration was working to provide public transit for the disabled. Outside the hall, demonstrators branded the secretary's plan as another “separate but equal" scheme and demanded that the federal government require all public transit systems be made accessible to the handicapped. Demonstrators not only blocked the entrances to the convention but also surrounded chartered buses that took delegates from their hotel to the convention center. The disabled activists represented a number of cities, including Denver, Syracuse, N.Y., Boston, El Paso, Los Angeles and Chicago. Additional photo on page 4. 28 Busted in D.C. The 28 disabled activists who were arrested for civil disobedience during the national convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) in Washington, D.C., last month are trying to raise $1500 to make their bail money by a Dec. 3 deadline. At the same time, they're preparing to carry their demand that the APTA members buy only wheelchair-lift equipped buses to the transit organization's regional convention in San Antonio on April 20. The Texas contingent from the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) under the leadership of Jim Parker of El Paso has been especially militant in their demands. Taking their lead from an editorial in the September Handicapped Coloradan, a coalition of of Texas disabled groups met in San Antonio and voted to ask transit systems in Texas to withdraw from APTA unless it goes on record supporting accessibility. The Colorado chapter of ADAPT was planning to introduce a similar resolution to Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD). APTA's position is that accessibility should be left to the discretion of the local transit provider, Although the Carter administration mandated accessibility in public transit, APTA was successful in getting that ruling thrown out in a l98l court battle. ADAPT maintains that the disabled have a civil right to public transit. Jack Gilstrap, APTA's executive vice president, reiterated that position as wheelchair demonstrators seized buses in front of the White House and hurled their chairs at police lines outside the Washington Hilton and Washington Convention Center during APTA's late September meeting. Gilstrap said that the funds just weren't there to support a mandatory system, adding that the additional burden might jeopardize some transit systems. However, since the convention ADAPT has been approached by APTA's new president, Warren Franks, the director of the Syracuse, N.Y., transit system, who has requested a meeting in Denver with wheelchair activists. "The Syracuse ADAPT group has been pretty active," said ADAPT spokesperson Wade Blank. "Franks must be pretty worried about what might happen there if he wants to meet with us.“ ADAPT was organized in Denver one year ago by some of the same groups and individuals who had been involved in forcing RTD to adopt a pro-accessibility policy when purchasing new buses. That battle too was highlighted by militant demonstrations with wheelers chaining themselves to the doors of RTD headquarters. In contrast, demonstrators restricted themselves to orderly pickets when APTA held its national convention in Denver in 1983. But ADAPT only abandoned its plans for civil disobedience after APTA met its demands to address the entire convention on accessibility. APTA's national staff fought that request and allegedly threatened to pull the convention out of Denver at the last minute, but finally agreed to allow ADAPT to address the meeting after Denver Mayor Federico Pena intervened. There was no question that ADAPT would be offered the same treatment at the Washington convention. Although they didn't get a spot on the agenda Blank said his group made their point by capturing the attention of the capital's media. Even before the convention opened, ADAPT made its presence known by joining forces with local D.C. activists to seize seven Metrobuses and block the five blocks along Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House during the afternoon rush hour. Demonstrators released the buses an hour later when D.C.’s Metro General Manager Carmen E. Turner agreed to meet with Washington disabled leaders to discuss their demands for a fully accessible system. No date has yet been set for that meeting, which ADAPT said marked an historic first in the Washington area. No arrests were made during that demonstration, although Washington police moved several demonstrators out of the street. But on the following Monday and Tuesday 28 demonstrators were arrested as they tried to block buses leaving the Washington Hilton for the convention center and again at the convention center itself. The police threw up lines as picketers arrived but were unable to halt the advance of the demonstrators, who wedged their chairs in the hall's doors or hurled their bodies onto the ground. Mike Auberger, one of those arrested, said the police "were abusive -- there's no doubt of that," but he added that this was probably pretty typical. “Let's face it," he said, "these guys probably have to deal with demonstrators all the time." They don't mess around when they get started. Auberger said he was grabbed by the hair and pulled back so that his chair was resting on its back wheels. Two other demonstrators were thrown from their chairs and taken to local hospitals where they were released after being treated for minor injuries. Police had to bring in special vans with wheelchair lifts in order to cart demonstrators off to jail, where they were fingerprinted and rushed into court. "Only the doorway between the holding cells and the courtroom was too narrow to get our chairs through," Auberger said, "so they had to take us in the back way." Some of the disabled picketers were surprised that the police reacted with such force, according to Auberger. "l think it opened a few eyes," he said. ADAPT filmed the demonstration, and a 20-minute edited version is being shown as part of a fundraiser to pay the bails of those arrested, about half of whom were from Denver. Congresswoman Pat Schroeder (D-Denver) has agreed tn help raise money, but because of previous campaign commitments said she would be unable to participate until after the first of the year.