- ენაAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

დასაწყისი / გალერეა / საძიებო სიტყვები White House + separate but equal

+ separate but equal 2

2

ADAPT (148)

ADAPT (148)

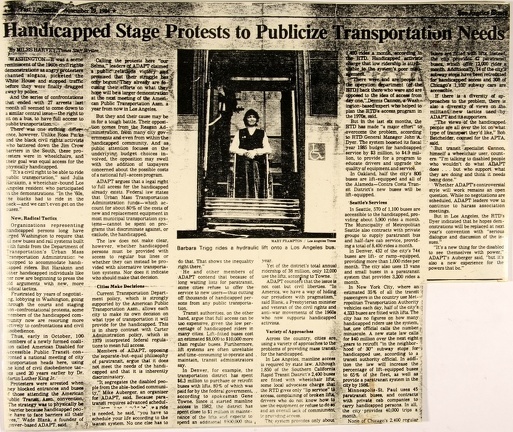

Name of newspaper illegible Los Angeles Times? November 19,1984 Handicapped Stage Protests to Publicize Transportation Needs by Miles Harvey, Times Staff Writer PHOTO: Mary Frampton / Los Angeles Times A tidy looking woman in pants and a vest, with a slight smile on her face, sits in a manual wheelchair on a bus. She is sitting in the accessible doorway, the access symbol visible on the side of the doorway. Below and beneath her is a metal panel, like the barrier on some lifts that keeps the person from rolling off the front of the lift. Caption reads: Barbara Trigg rides a hydraulic lift onto a Los Angeles bus. Article reads: Washington -- It was a scene reminiscent of the 1960s civil rights demonstrations as angry protesters chanted slogans, picketed the White House and stopped traffic before they were finally dragged away by police. And the series of confrontations that ended with 27 arrests last month seemed to come down to a similar central issue— the right to sit on a bus, to have full access to public transportation. There was one striking difference, however. Unlike Rosa Parks and the black civil rights activist who battered down the Jim Crow barriers in the South, these protesters were in wheelchairs, and their goal was equal access for the physically handicapped. “It's a civil right to be able to ride public transportation," said Julia Haraksin, a wheelchair-bound Los Angeles resident who participated in the demonstrations. “In the ‘60s, the blacks had to ride in the back—and we can't even get on the buses." New, Radical Tactics Organizations representing handicapped persons long have urged Washington to require that new buses and rail systems built with funds from the Department of Transportation's Urban Mass Transportation Administration be equipped to accommodate handicapped riders. But Haraksin and other handicapped individuals like her now are beginning to press the old arguments with new, more radical tactics. Frustrated by years of negotiating, lobbying in Washington, going through the courts and staging non-confrontational protests, some members of the handicapped community now are resorting more actively to confrontations and civil disobedience. Thus, early in October, 100 members of a newly formed coalition called American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit confronted a national meeting of city transportation heads here, using the kind of civil disobedience tactics used 30 years earlier by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Protesters were arrested when they blocked entrances and buses of those attending the American Public Transit Assn. convention. The strategy was to physically be a barrier because handicapped people have to face barriers all their lives," Wade Blank, a founder of Denver-based ADAPT said. Calling the protests here " Selma," leaders of ADAPT claimed victory and promised that their struggle has only begun. They already are focusing their efforts on what they hope will be a larger demonstration at the next meeting of the American Public Transportation Assn. a year from now in Los Angeles. But they and their cause may be in for a tough battle. Their opposition comes from the Reagan Administration, from many city governments and even from within the handicapped community. And as public attention focuses on the underlying budget choices involved, the opposition may swell with the addition of taxpayers concerned about the possible costs of a national full-access program. ADAPT argues that a legal right to full access for the handicapped already exists. Federal law states that Urban Mass Transportation Administration funds — which account for about 80% of the costs of new and replacement equipment in most municipal transportation systems—cannot be spent on programs that discriminate against, or exclude, the handicapped. The law does not make clear, however, whether handicapped persons must be provided with access to regular bus lines or whether they can instead be provided with alternative transportation systems. Nor does it indicate who should make that decision. Cities Make Decisions Current Transportation Department policy, which is strongly supported by the American Public Transportation Assn., allows each city to make its own decision on what type of transportation it will provide for the handicapped. This is in sharp contrast with Carter Administration policy, which in 1979 interpreted federal regulation to mean full access. Members of ADAPT, opposing the separate-but-equal philosophy of paratransit argue that it does not meet the needs of the handicapped and that it is inherently discriminatory. "It segregates the disabled people from the able-bodied community," Mike Auberger, an organizer for ADAPT, said. Because paratrasit requires advanced scheduling [unreadable] a ride is needed, he said, “you have to schedule your life according to the system. No one else has to do that. That shows the inequality right there." He and other members of ADAPT contend that because of long waiting lists for paratransit, some cities refuse to offer the service to new users - thus cutting off thousands of handicapped persons from any public transportation. Transit authorities, on the other hand, argue that full access can be too expensive, given the low percentage of handicapped riders in many cities. Lift-fitted buses cost an estimated $8,000 to $10,000 more than regular buses. Furthermore, lift systems are often unreliable and time-consuming to operate and maintain, transit administrators say. In Denver, for example, the transportation district has spent $63 million to purchase or retrofit buses with lifts. 80% of which was paid for by the federal government, according to spokesman Gene Towne. Since it started mainline access in 1982, the district has spent close to $1 million in maintenance of the lifts and expects to spend an additional $900,000 this year. Yet of the district's total annual ridership of 38 million, only 12,000 use the lifts, according to Towne. ADAPT counters that the issue is not cost but civil liberties. “In America we have a way of hiding, our prejudices with pragmatism," said Blank, a Presbyterian minister and veteran of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s who now supports handicapped activists. Variety of Approaches Across the country, cities are using a variety of approaches to the problems of providing mass transit for the handicapped. In Los Angeles, mainline access is required by state law. Although 1,850 of the Southern California Rapid Transit District‘s 2,400 buses are fitted with wheelchair lifts some local advocates charge that the RTD gives only "lip service" to access, complaining of broken lifts, drivers who do not know how to use the equipment or refuse to do so and an overall lack of commitment to providing access. The system provides only about 1,400 rides a month according to the RTD. Handicapped activists charge that the low ridership is attributable to the system's poor management. There were and are people in the operation department (of the RTD) back there who were and are opposed to the idea of access from day one," Dennis Cannon, a Washington-based expert who helped to plan the RTD's access program in the 1970s said. But in the last six months, the RTD has made "a major effort" to overcome the problem, according to RTD General Manager John A. Dyer. The system boosted its fiscal year 1985 budget for handicapped service by $3 million, to $4.9 million, to provide for a program to educate drivers and upgrade the quality of equipment and service. In Oakland, half the city's 800 buses are lift-equipped and all of the Alameda — Contra Costa Transit District's new buses will be lift-equipped. Seattle’s Services In Seattle, 570 of 1,100 buses are accessible to the handicapped, providing about 5,900 rides a month. The Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle also contracts with private groups to supply paratransit bus and half-fare cab service, providing a total of 8,400 rides a month in Denver. 432 of the city's 744 buses are lift- or ramp-equipped, providing more than 1,000 rides per month. The city also uses 13 vans and small buses in a paratransit system that provides 3,200 rides a month. In New York City, where an estimated 35% of all the transit passengers in the country use Metropolitan Transportation Authority vehicles each day. half of the city's 4,333 buses are fitted with lifts. The city has no figures on how many handicapped riders use the system, but one official calls the number minuscule. A new state law calls for $40 million over the next eight years to retrofit “in the neighborhood of 30" subway stops for handicapped use, according to a transit authority official. In addition the law will increase the percentage of lift-equipped buses to 65% of the fleet, as well as provide a paratransit system in the city by 1988. Minneapolis-St. Paul uses 45 paratransit buses and contracts with private cab companies to carry handicapped persons in all, the city provides 40.000 trips a month. None of Chicago's 2.400 regular buses are fitted with lifts. Instead the city provides 42 paratransit buses, which offer 12,000 rides a month. Additionally, 14 of the city's subway stops have been retrofitted for handicapped access and 300 of Chicago's 1,100 subway cars are accessible. If there is a diversity of approaches to the problem, there is also a diversity of views on the militant new tactics used by ADAPT and its supporters. The views of the handicapped people are all over the lot on what type of transport they'd like," Bob Batchelder, counsel for the APTA, said. But transit specialist Cannon, himself a wheelchair user, counters: “I'm talking to disabled people who wouldn't do what ADAPT does ... but who support what they are doing and think it needs being done." Whether ADAPT's controversial style will work remains an open question. While no negotiations are scheduled, ADAPT leaders vow to continue to harass association meetings. But in Los Angeles, the RTD's Dyer indicated that he hopes demonstrations will be replaced at next year's convention with “serious dialogue and discussion of the issues." "It’s a new thing for the disabled to see themselves with power," ADAPT's Auberger said, "but it's also a new experience for the powers that be." ADAPT (180)

ADAPT (180)

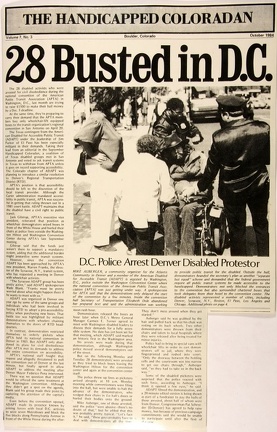

THE HANDICAPPED COLORADAN Volume 7, No. 3 Boulder, Colorado October 1984 PHOTO: A man in a leather brimmed hat, long hair beard and moustache down vest and jeans, seated in a motorized wheelchair (Mike Auberger), leans to his right as he is surrounded by abled bodied people. Back to the camera, a man plain clothes is partially in front of him, papers sticking out from his back pocket. A uniformed officer is also back to the camera and is holding Mike's arm which in front of Mike. A second uniformed officer is doing something behind Mike's back while a woman stands up on the sidewalk to his side watching with her hands on her hips. (She was an organizer with National Training and Information Center and was assisting with the Access Institute.) cation reads: D.C. Police Arrest Denver Disabled Protestor MIKE AUBERGER, a community organizer for the Atlantis Community in Denver and a member of the American Disabled for Accessible Transit (ADAPT) is arrested by Washington, D.C., police outside the Washington Convention Center where the national convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) was just getting under way. A spokesperson for APTA said that the demonstrations only delayed the start of the convention by a few minutes. Inside the convention hall Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole abandoned her prepared text and said the administration was working to provide public transit for the disabled. Outside the hall, demonstrators branded the secretary's plan as another “separate but equal" scheme and demanded that the federal government require all public transit systems be made accessible to the handicapped. Demonstrators not only blocked the entrances to the convention but also surrounded chartered buses that took delegates from their hotel to the convention center. The disabled activists represented a number of cities, including Denver, Syracuse, N.Y., Boston, El Paso, Los Angeles and Chicago. Additional photo on page 4. 28 Busted in D.C. The 28 disabled activists who were arrested for civil disobedience during the national convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) in Washington, D.C., last month are trying to raise $1500 to make their bail money by a Dec. 3 deadline. At the same time, they're preparing to carry their demand that the APTA members buy only wheelchair-lift equipped buses to the transit organization's regional convention in San Antonio on April 20. The Texas contingent from the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) under the leadership of Jim Parker of El Paso has been especially militant in their demands. Taking their lead from an editorial in the September Handicapped Coloradan, a coalition of of Texas disabled groups met in San Antonio and voted to ask transit systems in Texas to withdraw from APTA unless it goes on record supporting accessibility. The Colorado chapter of ADAPT was planning to introduce a similar resolution to Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD). APTA's position is that accessibility should be left to the discretion of the local transit provider, Although the Carter administration mandated accessibility in public transit, APTA was successful in getting that ruling thrown out in a l98l court battle. ADAPT maintains that the disabled have a civil right to public transit. Jack Gilstrap, APTA's executive vice president, reiterated that position as wheelchair demonstrators seized buses in front of the White House and hurled their chairs at police lines outside the Washington Hilton and Washington Convention Center during APTA's late September meeting. Gilstrap said that the funds just weren't there to support a mandatory system, adding that the additional burden might jeopardize some transit systems. However, since the convention ADAPT has been approached by APTA's new president, Warren Franks, the director of the Syracuse, N.Y., transit system, who has requested a meeting in Denver with wheelchair activists. "The Syracuse ADAPT group has been pretty active," said ADAPT spokesperson Wade Blank. "Franks must be pretty worried about what might happen there if he wants to meet with us.“ ADAPT was organized in Denver one year ago by some of the same groups and individuals who had been involved in forcing RTD to adopt a pro-accessibility policy when purchasing new buses. That battle too was highlighted by militant demonstrations with wheelers chaining themselves to the doors of RTD headquarters. In contrast, demonstrators restricted themselves to orderly pickets when APTA held its national convention in Denver in 1983. But ADAPT only abandoned its plans for civil disobedience after APTA met its demands to address the entire convention on accessibility. APTA's national staff fought that request and allegedly threatened to pull the convention out of Denver at the last minute, but finally agreed to allow ADAPT to address the meeting after Denver Mayor Federico Pena intervened. There was no question that ADAPT would be offered the same treatment at the Washington convention. Although they didn't get a spot on the agenda Blank said his group made their point by capturing the attention of the capital's media. Even before the convention opened, ADAPT made its presence known by joining forces with local D.C. activists to seize seven Metrobuses and block the five blocks along Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House during the afternoon rush hour. Demonstrators released the buses an hour later when D.C.’s Metro General Manager Carmen E. Turner agreed to meet with Washington disabled leaders to discuss their demands for a fully accessible system. No date has yet been set for that meeting, which ADAPT said marked an historic first in the Washington area. No arrests were made during that demonstration, although Washington police moved several demonstrators out of the street. But on the following Monday and Tuesday 28 demonstrators were arrested as they tried to block buses leaving the Washington Hilton for the convention center and again at the convention center itself. The police threw up lines as picketers arrived but were unable to halt the advance of the demonstrators, who wedged their chairs in the hall's doors or hurled their bodies onto the ground. Mike Auberger, one of those arrested, said the police "were abusive -- there's no doubt of that," but he added that this was probably pretty typical. “Let's face it," he said, "these guys probably have to deal with demonstrators all the time." They don't mess around when they get started. Auberger said he was grabbed by the hair and pulled back so that his chair was resting on its back wheels. Two other demonstrators were thrown from their chairs and taken to local hospitals where they were released after being treated for minor injuries. Police had to bring in special vans with wheelchair lifts in order to cart demonstrators off to jail, where they were fingerprinted and rushed into court. "Only the doorway between the holding cells and the courtroom was too narrow to get our chairs through," Auberger said, "so they had to take us in the back way." Some of the disabled picketers were surprised that the police reacted with such force, according to Auberger. "l think it opened a few eyes," he said. ADAPT filmed the demonstration, and a 20-minute edited version is being shown as part of a fundraiser to pay the bails of those arrested, about half of whom were from Denver. Congresswoman Pat Schroeder (D-Denver) has agreed tn help raise money, but because of previous campaign commitments said she would be unable to participate until after the first of the year.