- LangueAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Accueil / Albums / Mots-clés wheelchair lifts + Atlantis Community

+ Atlantis Community 7

7

ADAPT (122)

ADAPT (122)

Denver Post [This article continues on in ADAPT 123, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] Photo by Lyn Alweis: A short haired man in a jacket and dark slacks [Mel Conrardy] is lifted in his wheelchair from the sidewalk to a bus. The lift comes out of the front door of the bus and has railings on either side of the lift almost as tall as the seated man. Just by the bus door is a sign on the side of the bus that says "RTD Welcome Aboard." Caption: An RTD bus with wheelchair lift provides mobility for Mel Conrardy Title: Leaders of handicapped rate RTD service best in country By Norm Udevitz, Denver Post Staff Writer Disabled Denverites just a few years ago had as much chance of riding a bus as they did of climbing Mount Everest. “It was brutal the way RTD treated us,” said Mike Auberger, an official in the Atlantis Community, for the disabled and a leader in the fight that has turned the Regional Transportation District’s handicapped service around. In the 1970s and early 1980s, RTD busses then rarely equipped with wheelchair lifts, often left wheelchair-bound riders stranded on streets. Drivers, lacking training in dealing with visually or language impaired people, panicked when blind or deaf riders tried to board buses. “It used to be that even in the dead of winter, when it was below zero, those of us in wheelchairs would wait 2 or 3 hours for a bus to finally stop," Auberger recalls. “And often the lift was broken and we couldn't get on the bus anyway. And usually the drivers were rude and angry. They would tell us that we were ruining their schedules." But conditions have changed, Auberger says: “Right now, Denver has the most accessible public transit system for the handicapped — and all the public - in the country." Debbie Ellis, a state social services worker who heads the agency's Handicapped Advisory Council, agrees, saying: “It took a lot of pressure, but RTD has responded and now the bus system is doing a good job of serving the handicapped." Leaders of national programs for the disabled also agree. In fact, the President's Committee on Employment of the Handicapped will bring 5,000 delegates, many of them handicapped, to its national conference in Denver in April. This will be the first time in four decades the group has held its national session outside of Washington DC. “One of the key reasons we're meeting in Denver this year is because it just might be the most comfortable city in the country for the handicapped,” says Sharon Milcrut, head of the Colorado Coalition for Persons with Disabilities, which is hosting the conference. “A very important aspect of that comfort," she notes, “is how accessible the transit system is for the handicapped.” It didn't get that way easily. In the decade between 1974 and 1984, handicapped activists had to pressure indifferent RTD administrators and directors. Each gain was hard won. “We used every tactic in the book, from lawsuits to bus blockades on the street and sit-ins at the RTD offices," says Wade Blank, an Atlantis group director. “The lawsuits didn't help much but when we took to the streets in the late 1970s, I think that's when we started getting their attention." Blank and others also say the 1984 hiring of Ed Colby as RTD general manager helped. Before he arrived, less than half of the 750 RTD buses had wheelchair lifts, which often were in disrepair. Training for drivers to learn how to deal with handicapped riders was minimal. Agency directors resisted change. RTD relied heavily on a costly special van operation called Handyride - a door-to-door pickup service for handicapped. It has cost $13[? glare makes number hard to read] million to run since it began in 1975. “Over the past couple of years the turnaround has been phenomenal," Auberger says. “All of RTD's new buses are being ordered with lifts and older buses are being retrofitted." By 1986's end, almost 80 percent of the bus fleet — 608 of 765 buses — had wheelchair lifts; 82 percent of the fleet's 6,242 daily trips are now accessible for the disabled. Plans call for the fleet to be 100 percent lift-equipped by 1987's end. “The lifts aren't breaking down all the time now, either," Auberger said, noting that agency officials found drivers had neglected to report broken lifts: “That way the lifts stayed broken and drivers had an excuse for not picking us up. A bunch of people were fired over that and others realized that Colby wasn't kidding about improving handicapped service." Driver training also has improved dramatically. “It isn't perfect yet,” Ellis of the advisory council says. "But everyone is working hard at it. What we are finding is that 20 percent of the drivers understand that they are moving people, all kinds of people, and they're really great with the handicapped. “Another 20 percent figure their job is to move buses and to heck with passengers, all kinds of passengers. That bottom 20 percent probably won't ever change. So we're working real hard on the 60 percent in between," Ellis says. Drivers, for example, learn to help blind riders. “That’s an improvement that helps the disabled, but it also helps regular passengers who are newcomers to the city,” Ellis says. All the improvements haven't come cheap. Since 1974, more than $5million has been spent on lifts and lift maintenance, most of the expense was incurred in the last three years. RTD plans to spend $9 million more in the next six years to keep the fleet up to its current standards and pay for more driver training. Another $4 million will be spent on HandyRide service. Ironically, Auberger and Ellis both say one of the biggest problems remaining is getting more handicapped people to use mass transit. “There are no reliable figures," Ellis says. “But we think there are about 20,000 handicapped people in the metro area and only about 200 or 300 are using buses on a regular basis." Auberger, confined to a wheelchair after breaking his neck in an accident ll years ago, complains: “The medical system builds a bubble around handicapped people and makes them think they have to be protected. "That's just not true in most cases. So one of the things we're doing now is educating the handicapped to overcome their fears. We've finally got a bus system that works for us and we want the disabled to use it." Photo by Lyn Alweis: A rather straight looking man [Mel Conrardy] in a white jacket, big mittens, and a motorized wheelchair, wears a slight smile as he rides the bus. Someone in a dark jacket stands beside him, and behind him, further back on the bus, other riders are sitting on the bus seats. Caption reads: A bus seat folds up to anchor Mel Conrardy's wheelchair to the floor. Conrardy commutes to work at the Atlantis Community.![ADAPT (109) (4467 visites) The Denver Post Friday, Dec. 18, 1981

[Headline] Handicapped Will Protest RTD Wheelc... ADAPT (109)](_data/i/upload/2016/05/10/20160510142135-e4044ea4-me.jpg) ADAPT (109)

ADAPT (109)

The Denver Post Friday, Dec. 18, 1981 [Headline] Handicapped Will Protest RTD Wheelchair-Lift Ban By George Lane Denver Urban Affairs Writer The board of directors of the Regional Transportation District Thursday made it official – there will be no wheelchair lifts on 89 high-capacity buses expected to be delivered in 1983. The board actually decided a month ago there would be no lifts on the new buses, but they have been hedging on finalizing that action because of objections voiced by the area’s disabled community. Following the vote on the lifts, Wade Blank, co-administrator for the Atlantis Community for the disabled and organizer of the protest against the RTD action, told the transit directors that members of the handicapped community view the action as a violation of their human rights and they will respond to that violation Jan. 4. Blank later said members of the disabled community will be in “training for civil disobedience” between now and Jan. 4. He said beginning Jan. 4, 10 disabled persons in wheelchairs will stage a sit-in in the office of L.A. “Kim” Kimball, RTD’s executive director and general manager. “Everyday during the month of January, 10 disabled people will be occupying Kimball’s office,” Blank said. They won’t have any able-bodied people with them – and if they’re arrested they will be replaced by 10 more. At the conclusion of the board meeting, Kimball told the directors that the RTD staff will take steps to try to prevent this action, but he doesn’t think it proper to discuss those steps at this time. The RTD board during its Nov. 19 meeting voted to save more than a million dollars by not ordering the lifts on the new buses. The RTD staff recommended this action because they said the lifts are expensive (more than $12,000 per bus) and difficult to maintain. The staff proposal was to use the articulated buses on high ridership bus routes, freeing regular buses with wheelchair lifts to provide better service for the handicapped. A delegation from the handicapped community objected to this proposal, with arguments that RTD officials had promised several years ago that 50 percent of the district’s bus fleet would be made accessible to wheelchair-bound riders and all new buses would be ordered with lifts. About 25 disabled persons from Atlantis staged a wheelchair-bound sit-in following the November meeting until Kimball and three board members promised to attempt to get the entire board to reconsider the action. Thursday’s vote was the outcome of that promise. ADAPT (102)

ADAPT (102)

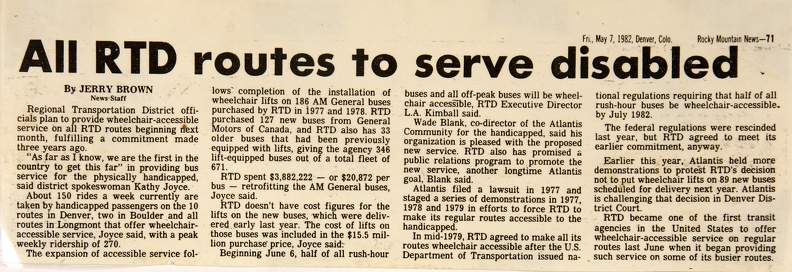

Rocky Mountain News Friday, May 7, 1982 All RTD routes to serve disabled By Jerry Brown News-Staff Regional Transportation District officials plan to provide wheelchair-accessible service on all RTD routes beginning next month, fulfilling a commitment made three years ago. “As far as I know, we are the first in the country to get this far,” in providing bus service for the physically handicapped, said district spokeswoman Kathy Joyce. About 150 rides a week currently are taken by handicapped passengers on the 10 routes in Denver, two in Boulder and all routes in Longmont that offer wheelchair-accessible service, Joyce said, with a peak weekly ridership of 270. The expansion of accessible service follows completion of the installation of wheelchair lifts on 186 AM General buses purchased by RTD in 1977 and 1978. RTD purchased 127 new buses from General Motors of Canada, and RTD also has 33 older buses that had been previously equipped with lifts, giving the agency 346 lift-equipped buses out of a total fleet of 671. RTD spent $3,882,222 - or $20,872 per bus - retrofitting the AM General buses, Joyce said. RTD doesn't have cost figures for the lifts on the new buses, which were delivered early last year. The cost of lifts on those buses was included in the $15.5 million purchase price, Joyce said. Beginning June 6, half of all rush-hour buses and all off-peak buses will be wheelchair accessible, RTD Executive Director L.A. Kimball said. Wade Blank, co-director of the Atlantis Community for the handicapped, said his organization is pleased with the proposed new service. RTD also has promised a public relations program to promote the new service, another longtime Atlantis goal, Blank said. Atlantis filed a lawsuit in 1977 and staged a series of demonstrations in 1977, 1978 and 1979 in efforts to force RTD to make its regular routes accessible to the handicapped. In mid-1979, RTD agreed to make all its routes wheelchair accessible after the U.S. Department of Transportation issued national regulations requiring that half of all rush-hour buses be wheelchair-accessible by July 1982. The federal regulations were rescinded last year, but RTD agreed to meet its earlier commitment, anyway. Earlier Atlantis held more demonstrations to protest RTD’s decision not to put wheelchair lifts on 89 new buses scheduled for delivery next year. Atlantis is challenging that decision in Denver District Court. RTD became one of the first transit agencies in the United States to offer wheelchair-accessible service on regular routes last June when it began providing such service on some of its busier routes.![ADAPT (94) (3044 visites) Rocky Mountain News Wed., Dec. 9,1981, Denver, Colo.

[Headline] Handicapped set back in battle... ADAPT (94)](_data/i/upload/2016/05/10/20160510141730-4aa8d096-me.jpg) ADAPT (94)

ADAPT (94)

Rocky Mountain News Wed., Dec. 9,1981, Denver, Colo. [Headline] Handicapped set back in battle for lifts on buses The Operations Committee of the Regional Transportation District’s board of directors voted 4-0 Tuesday to stick by an earlier proposal that RTD buy 89 articulated buses scheduled for delivery in 1983 without wheelchair lifts. Its action seriously diminishes the chances that the board will reverse its decision of Nov. 19 to delete the lifts from the articulated buses. But RTD Executive Director L.A. Kimball and three board members agreed to ask the board to reconsider the action after members of the Atlantis Community for the disabled staged a sit-in at RTD headquarters on the day of the earlier vote to protest the decision. The board held a three-hour special meeting on Dec. 1 to hear appeals from the handicapped to put wheelchair lifts on the buses. Atlantis spokesman Wade Blank said members of his organization have been discussing the issue with individual board members and plan to meet with Kimball next week. Blank said he expects to fall short of the 11 votes needed for the board to reverse its position when the issue comes up at the board’s regular meeting on Dec. 17. Blank renewed Atlantis’ threat to file a lawsuit challenging the decision not to buy the lifts and said Atlantis will resume demonstrating against RTD. Atlantis filed a lawsuit in federal court and staged a series of demonstrations aimed at RTD a few years ago after RTD bought nearly 200 AM General buses without wheelchair lifts. U.S. District Judge Richard Matsch ruled against Atlantis in that case, but the case was on appeal when Atlantis and RTD in 1979 negotiated a settlement under which RTD agreed to make half of its peak-hour fleet accessible to the handicapped. The settlement was reached after the federal Department of Transportation issued regulations requiring that all new buses bought with federal funds be equipped with wheelchair lifts and that half of all buses used for peak-hour service be accessible to the handicapped. Those regulations were rescinded by the department in July. RTD officials ordered the articulated buses with lifts in March, while the regulations requiring lifts on new buses were still in effect. Buying the buses without lifts will save $1.1 million, 80 percent of RTD’s federal funds, RTD officials said.![ADAPT (84) (2608 visites) Denver Post

[Headline] RTD Cries Foul Over 'Stuck' Rider

Photo to right of article, Denver Pos... ADAPT (84)](_data/i/upload/2016/05/10/20160510141356-3f27fb00-me.jpg) ADAPT (84)

ADAPT (84)

Denver Post [Headline] RTD Cries Foul Over 'Stuck' Rider Photo to right of article, Denver Post photo by Ken Bisio: A woman [Beverly Furnice] who is in a motorized wheelchair with her long legs extended straight in front of her, is framed by the front door of a bus. She has her left arm up above her face, as if to protect herself and she has a wary expression on her face. Behind her a large man in shirt sleeves and a tie is holding her wheelchair's push handles and appears to be trying to maneuver her off the bus. There does not appear to be a lift deployed. Part of the universal access symbol is visible next to the door of the bus. Caption reads: Beverly Furnice is helped off an RTD bus. She wound up on a long ride. By BRAD MARTISIUS Denver Post Staff Writer In the 1960s, the Kingston Trio recorded a song about a man trapped on the MTA, doomed to ride forever in the Boston subway. That song seemed prophetic Thursday when a handicapped woman found herself unable to get off an Regional Transportation District bus and ended up seeing much of Denver before finally being assisted off by RTD officials, anxious to avoid a scene. The incident, however, raised the hackles of RTD officials, who felt they were the victims of a ploy by members of the Atlantis Community, 4536 E. Colfax Ave., an organization that aids the handicapped. And Wade Blank, co-director of the Atlantis Community, said he wasn't too happy with RTD substituting one type of RTD lift-bus for another type, leading to a very long ride for the handicapped woman. THE WOMAN, Beverly Furnice, 43, of 1135 Josephine St., has legs which are rigid perpendicular to her body and don't bend because of her condition. This makes it impossible for her to ride in an automobile or taxi, a problem exacerbated by the fact that her wheelchair weighs 400 pounds and doesn't fold. Blank said she rides the bus to work daily, and usually has no problems. However, he said RTD put a different bus on the route Thursday. Asked why Miss Furnice didn't just wait for the next bus, Blank said the special buses on that route run only every two hours. Miss Furnice’s wheelchair is elevated and is longer than many wheelchairs, and was unable to negotiate the bus‘ interior without help, even though the bus was equipped with a ramp to aid handicapped persons in boarding. When she got on the bus, she was aided by Atlantis Community members. But when the time came for her to get off, there was no one to help, and the busdriver, who wouldn't identify himself, refused to leave his driver’s seat, so she had no choice but to continue riding the bus, taking the circuit out to Red Rocks and back. ACCORDING TO Dick Thomas, executive director for RTD‘s department of program management, the driver was assured that help would be available for Miss Furnice when she got off the bus. He said the driver made it clear when she boarded that he wouldn't help her get off. “The drivers have the right to do that," Thomas explained. “It’s in their union contract, and it's there to protect the other passengers. It’s up to the driver's discretion. He can help, but he doesn't have to if he feels it would be hazardous to leave the driver's seat." Thomas said Blank boarded the bus at Miss Furnice's stop and argued with the bus driver, but refused to help her get off the bus. About two hours later, several wheelchair-bound persons from the community were waiting at Miss Furnice’s stop, with the intention of boarding the bus also and riding in sympathy with her. Blank said Friday that the bus incident wasn't a planned protest, but that the wrong bus had arrived at least three times before and that this time Atlantis community decided to make a point about the type of bus used “which was bought without our permission." Blank said RTD frequently replaces one type of lift-bus with other, less accessible types, creating potential problems. “We've asked RTD not to use the less-accessible buses, for just this reason," Blank said. “It's not a problem if the driver is sensitive to the needs of the handicapped." Thomas said the lift-buses, while designed to meet some of the needs of the handicapped, never will be able to meet all the needs of everyone. He said there always will be some handicapped who just won’t be able to use them. ADAPT (77)

ADAPT (77)

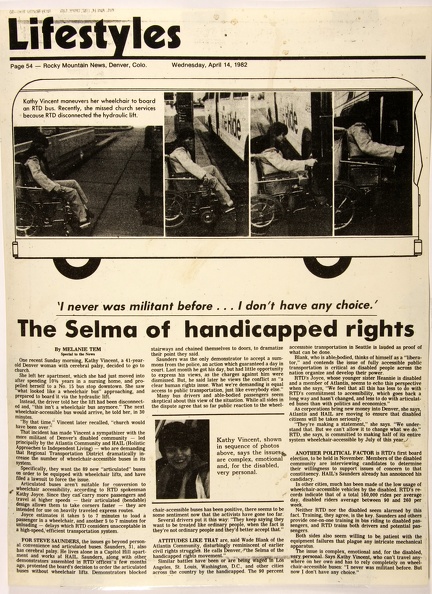

The Selma of handicapped rights By Melanie Tem One recent Sunday morning, Kathy Vincent, a 41-year-old Denver woman with cerebral palsy, decided to go to church. She left her apartment, which she had just moved into after spending years in a nursing home, and propelled herself to a No.15 bus stop downtown. She saw "what looked like a wheelchair bus" approaching, and prepared to board it via the hydraulic lift. Instead, the driver told her the lift had been disconnected and, "this isn't a wheelchair bus anymore." The next wheelchair-accessible bus would arrive, he told her, in 30 minutes. "By that time," Vincent later recalled, "church would have been over." That incident has made Vincent a sympathizer with the more militant of Denver's disabled community - led principally by the Atlantis Community and HAIL(Holistic Approaches to Independent Living) - who are demanding that Regional Transportation District dramatically increase the number of wheelchair-accessible buses in its system. Specifically, they want the 89 new "articulated" buses on order to be equipped with wheelchair lifts, and have filed a lawsuit to force the issue. Articulated buses aren't suitable for conversion to wheelchair accessibility, according to RTD spokesman Kathy Joyce. Since they can carry more passengers and travel at higher speeds - their articulated (bendable) design allows them to take corners faster - they are intended for use on heavily traveled express routes. Joyce estimates it takes 5 to 7 minutes to load a passenger in a wheelchair, and another 5 to 7 minutes for unloading - delays which RTD considers unacceptable in a high-speed, efficient transportation system. FOR STEVE SAUNDERS, the issues go beyond personal convenience and articulated buses. Saunders, 31, also has cerebral palsy. He lives alone in a Capitol Hill apartment and works at HAIL. Saunders, along with other demonstrators assembled in RTD offices a few months ago, protested the board's decision to order the articulated buses without wheelchair lifts. Demonstrators blocked stairways and chained themselves to doors, to dramatize their point they said. Saunders was the only demonstrator to accept a summons from the police, an action which guaranteed a day in court. Last month he got his day, but had little opportunity to express his views, as the charges against him were dismissed. But, he said later he views the conflict as “a clear human rights issue. What we're demanding is equal access to public transportation, just like everybody else." Many bus drivers and able-bodied passengers seem skeptical about this view of the situation. While all sides in the dispute agree that so far public reaction to the wheelchair-accessible buses has been positive, there seems to be some sentiment now that the activists have gone too far. Several drivers put it this way: "They keep saying they want to be treated like ordinary people, when the fact is they're not ordinary people and they'd better accept that." Attitudes like that are, said Wade Blank of the Atlantis Community, disturbingly reminiscent of earlier civil rights struggles. He calls Denver, "the Seima of the handicapped rights movement." Similar battles have been or are being waged in Los Angeles, St. Louis, Washington, D.C., and other cities across the country by the handicapped. The 90 percent accessible transportation in Seattle is lauded as proof of what can be done. Blank, who is able-bodied, thinks of himself as a "liberator," and contends the issue of full accessible public transportation is critical as disabled people across the nation organize and develop their power. RTD's Joyce, whose younger sister Heannie is disabled and a member of Atlantis, seems to echo this perspective when she says, "We feel that all this has less to do with RTD’s commitment to accessibility, which goes back a long way and hasn't changed, and less to do with articulated buses than with politics and economics." As corporations bring new money into Denver, she says, Atlantis and HAIL are moving to ensure that disabled citizens will be taken seriously. "They're making a statement," she says. "We understand that. But we can't allow it to change what we do." RTD, she says, is committed to making half of its entire system wheelchair-accessible by July of this year. ANOTHER POLITICAL FACTOR is RTD's first board election, to be held in November. Members of the disabled community are interviewing candidates to determine their willingness to support issues of concern to that constituency. HAlL's Saunders already has announced his candidacy. In other cities, much has been made of the low usage of wheelchair-accessible vehicles by the disabled. RTD's records indicate that of a total 160,000 rides per average day, disabled riders average between 90 and 260 per week. Neither RTD nor the disabled seem alarmed by this fact. Training, they agree, is the key. Saunders and others provide one-on-one training in bus riding to disabled passengers, and RTD trains both drivers and potential passengers. Both sides also seem willing to be patient with the equipment failures that plague any intricate mechanical apparatus. The issue ls complex, emotional and, for the disabled, very personal. Says Kathy Vincent, who can't travel anywhere on her own and has to rely completely on wheelchair-accessible buses: “l never was militant before. But now l don’t have any choice." ADAPT (32)

ADAPT (32)

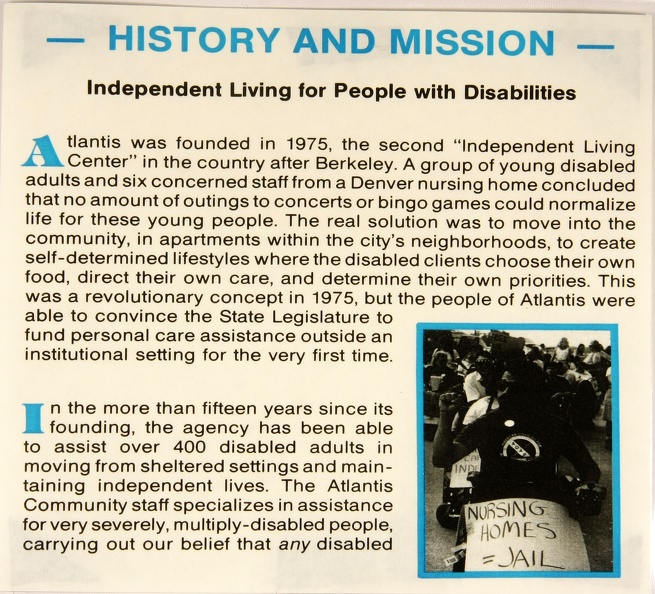

History and Mission Independent Living for People with Disabilities [This brochure continues in ADAPT 33, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] PHOTO by Tom Olin (bottom right): A man (George Roberts) in wheelchair raises the power fist with his right hand. He is carrying a sign that reads "Nursing Homes = Jail." Behind him a group of other wheelchair protesters are lining up. Atlantis was founded in 1975, the second “Independent Living Center” in the country after Berkeley. A group of young disabled adults and six concerned staff from a Denver nursing home concluded that no amount of outings to concerts or bingo games could normalize life for these young people. The real solution was to move into the community, in apartments within the city’s neighborhoods, to create self-determined lifestyles where the disabled clients choose their own food, direct their own care, and determine their own priorities. This was a revolutionary concept in 1975, but the people of Atlantis were able to convince the State Legislature to fund personal care assistance outside an institutional setting for the very first time. In the more than fifteen years since its founding, the agency has been able to assist over 400 disabled adults in moving from sheltered settings and maintaining independent lives. The Atlantis Community staff specializes in assistance for very severely, multiply-disabled people, carrying out our belief that any disabled person can live outside an institution, if s/he is willing to accept the risks and inconveniences in order to enjoy self-determination and liberty. To that end, the staff and clients are experts in helping with everything from finding an apartment to applying for benefits, from grocery shopping to weddings, from cooking training to camping trips. The assistance with daily living activities and the basic skills training and reinforcement offered are complemented by the trained and state-certified staff of home health aides and their supervisors who visit the clients at home as often as needed — usually several times a day. The people of Atlantis also offer other independent living services to people throughout the nation — ranging from information and referral services to assertiveness training and technical assistance. The city of Denver and the Atlantis Community have become a mecca for disabled people seeking an accessible environment and comprehensive services. PHOTO by Tom Olin (top left corner): 4 people in wheelchairs (left to right, Joe Carle, Diane Coleman, Bob Kafka and Mark Johnson) lead a march. Everyone is dressed in revolutionary war garb -- wigs, three cornered hats, jackets with braid on them. Over their heads is a large flag, the ADAPT flag. PHOTO (bottom right): An older man (Mel Conrardy) in a white jacket and pants, sits in a wheelchair on a lift at the front door of a bus. To his right on the side of the bus door it says RTD Welcome Aboard. Mel looks relaxed and is smiling.