- שפהAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

בית / אלבומים / תגיות APTA - American Public Transit Association + Dallas

+ Dallas 5

5

![ADAPT (208) (12185 visits) The San Diego Union March 2, 1986, page A3

The West [section of newspaper]

Drawing of Mr Louv'... ADAPT (208)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/08/20160108130058-7eec73bc-sm.jpg) ADAPT (208)

ADAPT (208)

The San Diego Union March 2, 1986, page A3 The West [section of newspaper] Drawing of Mr Louv's head: White, youngish, short dark hair parted on side and glasses. [Headline] Transportation news for handicapped ‘a nightmare’ By Richard Louv The WHEELCHAIRS are rolling. On Jan. 16, in Dallas, handicapped demonstrators decrying "taxation without transportation," chained themselves to public buses, forcing traffic detours for nearly six hours. In downtown Los Angeles, last Oct 7, more than 200 people in wheelchairs rolled down the middle of Wilshire Boulevard to protest the policies of the American Public Transit Association. In San Antonio last April, 60 handicapped people staged a four-hour protest at the city's public transit offices, causing 90 nervous bus company employees to lock themselves in their offices for an hour until the transit association agreed to meet the demonstrators. And on Feb. 13, Houston police arrested eight demonstrators in wheelchairs and carted them off to jail in lift-equipped police vans. Their sentencing is tomorrow. and a representative of the Denver-based American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit told me that if the protesters “spend weeks in jail, it will be like when Martin Luther King went to jail in Birmingham. People will realize we're not just out playing in the street" What's going on here? The disabled~rights movement isn't new, of course. It began in Berkeley in the late 60s, and ultimately resulted in a government shift from segregating handicapped people to "mainstreaming" them into the rest of society. According to Cyndi Jones, publisher of San Diego-based Mainstream, a national magazine for the “able-disabled," some of the first generation leaders "got co-opted by government jobs, and frustration for the rest of us has been growing." A raft of laws were passed during the 1970s, but the laws. says Jones. still haven't been fully implemented. “The Rehabilitation Act promised disabled people equal access to public transportation facilities and education and employment. In education. the news has been good, but transportation is a nightmare." IN 1981, CONTENDING THAT putting lifts on buses was an unrealistic expense, the American Public Transit Association sued the federal government and won. Most cities stopped deploying the mechanical lifts that enable people using wheelchairs, walkers and crutches to board buses. The favored transportation method, at least among municipal officials, became small, subsidized "dial-a-ride" vans. "That's like putting us back in segregated schools," says Jones. The disability groups have a number of other complaints, some of them affecting many more people — lack of housing, attended care, airplane facilities. But what it has come down to is the symbol of lifts. While some disabled people are satisfied with the dial-a-ride approach, Jones says "taking a van service can cost you $60 to get to work and back. You have to call and reserve a ride — sometimes days in advance, and these services can't always guarantee a specific arrival time or even take you home. As a result, a lot of us can't afford to work, or we just stay home." California still requires lifts on all new buses, but Jones contends that the transit companies can develop some creative delaying tactics. Roger Snoble, the San Diego Transit Corp.'s general manager, agrees with her. "Some cities," he says, "don't care whether the lifts work once they put them on. They just let them go, and then say the lifts don't work." Jones, by the way, gives relatively high marks to San Diego's bus system; not so to the trolley. which she calls “miserable for handicapped people." As she sees it, a new generation of leaders in the disabled~rights movement is just now coming of age. They have some powerful opponents —— with some powerful statistics. Jim Mills, chairman of the Metropolitan Transit Development Board, has pointed out that in Los Angeles the average cost per ride of the various dial-a-ride systems “is $6.22, while the costs associated with a one-way trip on a bus for a person in a wheelchair is $300." And in a recent interview, Colorado Gov. Richard Lamm told me, "I think it is a myopic use of capital to try to put a lift on every bus in America. It costs the St. Louis bus system $700 per ride to maintain lifts." But Roger Snoble says it costs San Diego far less — $166 per ride (as of a year ago, "the last time we checked, and we expect the cost to continue to decline because of dramatically improving technology." And when I mentioned Lamm's figures to Dennis Cannon, the chief federal watchdog for the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Transit Compliance Board, he said, “Lamm's figures are at least six or seven years old, and wrong. These same figures get used a lot by lift opponents, but they're based on one of the very first generations of lifts, which were poorly administered and poorly installed by St. Louis during one the worst winters in Missouri history." He points out that Seattle, with one of the best bus systems in the nation, has managed to get the per-ride costs down to $5 or $10, depending on the amount of ridership. And Denver has decreased its lift failures from 25 a day to five within the last year. WITH ADVANCES LIKE this, combined with the increasing demands from disabled groups, a number of cities have decided that the lifts make economic sense — maybe not in this decade, but soon. "What's about to hit is a wave of people who expect to have equal access, the children of the mainstreaming movement," says Jones. During the past decade, government and society encouraged disabled people to work independently, and now that generation will be at bus stops and trolley stations all over the country, waiting to go to work. With them will be aging baby boomers, a giant crop of potentially disabled seniors. "Only one~third of the disabled population is employed. but two-thirds of disabled people are not receiving any kind of benefits," says Andrea Farbman, a spokeswoman for the National Council on the Handicapped. “Still. we're spending huge amounts of money keeping people unemployed — $60 billion dollars a year, but only $2 billion going to rehabilitation and special education." One rough estimate, says Farbman, is that 200,000 handicapped people would enter the work force if the travel barriers were eliminated. adding as much as $1 billion in annual earnings to the economy. The tragedy is this: While politicians wrangle over the costs of bus lifts, nobody has studied how much money could be saved in government benefits, and how much could be gained through taxes and added national productivity if more handicapped Americans were employed. ADAPT (266)

ADAPT (266)

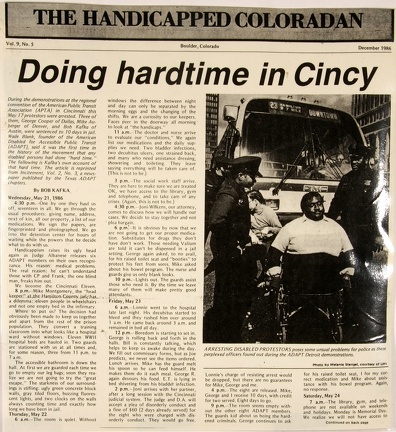

THE HANDICAPPED COLORADAN Vol.9, No. 5 Boulder Colorado December 1986 [This article continues in ADAPT 259, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] PHOTO by Melanie Stengel, courtesy of UPI: A large heavy set man with no legs (Jerry Eubanks) sits in his manual wheelchair in front of a city bus. He has a determined and frustrated look on his face. Behind him and up against the front of the bus you can see another protester in a wheelchair (Greg Buchanan). On either side of Jerry is a uniformed officer, apparently unsure of how to proceed. One stands with his hand on this hip, the other officer is on Jerry's other side and is looking toward the first policeman, as if for guidance. caption reads: ARRESTING DISABLED PROTESTORS poses some unusual problems for police as these perplexed officers found out during the ADAPT Detroit demonstrations. Title: Doing hardtime in Cincy During the demonstrations at the regional convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) in Cincinnati this May 17 protestors were arrested. Three of them, George Cooper of Dallas, Mike Auberger of Denver, and Bob Kafka of Austin, were sentenced to 10 days in jail. Wade Blank, founder of the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT), said it was the first time in the history of the movement that any disabled persons had done “hard time. ” The following is Kafka's own account of that hard time. The article is reprinted from Incitement, Vol. 2, No. 3, a newspaper published by the Texas ADAPT chapters. By BOB KAFKA Wednesday, May 21, 1986 4:30 p.m.— One by one they haul us off, seventeen in all. We go through the usual procedures: giving name, address, next of kin, all our property, a list of our medications. We sign the papers, are fingerprinted and photographed. We go into the detention center for hours of waiting while the powers that be decide what to do with us. Handicapism raises its ugly head again as judge Albanese releases six ADAPT members on their own recognizance. His reason: medical problems. The real reason: he can't understand those with CP and Frank, the one blind man, freaks him out. We become the Cincinnati Eleven. 8 p.m.—Mike Montgomery, the “head keeper" at the Hamilton County, jail, has a dilemma: eleven people in wheelchairs and not one empty bed in the infirmary. Where to put us? The decision had obviously been made to keep us together and apart from the rest of the prison population. They convert a training classroom into what looks like a hospital ward without windows. Eleven WWII hospital beds are hauled in. Two guards are stationed with us at all times and, for some reason, three from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. The accessible bathroom is down the hall. At first we are guarded each time we go to empty our leg bags; soon they realize we are not going to try the “great escape." The starkness of our surroundings is stifling: ugly green concrete block walls, gray tiled floors, buzzing fluorescent lights, and two clocks on the walls always counting time and exactly how long we have been in jail. Thursday, May 22 6 a.m.- The room is quiet. Without windows the difference between night and day can only be separated by the morning eggs and the changing of the shifts. We are a curiosity to our keepers. Faces peer in the doorway all morning to look at "the handicaps." ll a.m.— The doctor and nurse arrive to evaluate our "conditions," We again list our medications and the daily supplies we need. Two bladder infections, two decubitus ulcers, one strained back, and many who need assistance dressing, showering and toileting. They leave saying everything will be taken care of. (This is not to be.) 3 p.m.- The social work staff arrive. They are here to make sure we are treated OK, we have access to the library, gym and telephone, and to take care of any crises. (Again, this is not to be.) 4:30 p.m.- Joni Wilkens, our attorney, comes to discuss how we will handle our cases. We decide to stay together and not plea bargain. 6 pm.- It is obvious by now that we are not going to get our proper medication. Substitutes for drugs they don't have don't work. Those needing Valium are told it can't be dispensed in a jail setting. George again asked, to no avail, for his raised toilet seat and "booties" to protect his feet from sores. Mike asked about his bowel program. The nurse and guards give us only blank looks. 10 p.m.—Lights out. The guards assist those who need it. By the time we leave many of them will make pretty good attendants. Friday, May 23 6 a.m.-Lonnie went to the hospital late last night. His decubitus started to bleed and they rushed him over around l a.m. He came back around 3 a.m. and remained in bed all day. 12 p.m.- Boredom is starting to set in. George is rolling back and forth in the halls. Bill is constantly talking, which helps to keep us awake during the day. We fill out commissary forms, but as Joe predicts, we never see the items ordered. Lunch arrives, Mike has the guard melt his spoon so he can feed himself. He makes them do it each meal. George R. again devours his food. E.T. is lying in bed shivering from his bladder infection. 2 p.m.- Joni arrives with her partner, after a long session with the Cincinnati judicial system. The judge and D.A. will accept a plea of disorderly conduct and a fine of $60 (2 days already served) for the eight who were charged with disorderly conduct. They would go free. Lonnie's charge of resisting arrest would be dropped, but there are no guarantees for Mike, George and me. 4 p.m.- The eight are released, Mike, George and I receive 1O days, with credit for two served. Eight days to go. 9 p.m.- The room seems empty without the other eight ADAPT members. The guards kid about us being the hardened criminals. George continues to ask for his raised toilet seat, I for my correct medication and Mike about assistance with his bowel program. Again-no response. Saturday, May 24 7 a.m.-The library, gym, and telephone are not available on weekends and holidays. Monday is Memorial Day. We realize we will not have access to these amenities until Tuesday. Very much like a hospital stay. We also realize our medical needs will not be met; however, we continue our demands that something be done so Mike and George can get the help they need with their bowel program. Security continues to relay this to the medical staff. Medical staff continues to say it is security’s responsibility. This double think has been going on four days now, with no assistance given so far. 2 p.m.— George is beginning to have adverse effects from Valium withdrawal. Mike is having more and worse spasms because the substitute medications are not working. I have no idea if the substitute antibiotic is doing any good at all. Sunday, May 25 4 p.m.-The day passes as usual. Up at 6 a.m. with breakfast of cold eggs and boiled water that had looked at a coffee bean. After lunch our daily request for medication, supplies, and bowel program assistance is duly noted in the guard’s record book, but as usual no action. Joni and Art Wademan, a minister who has been invaluable throughout the week in Cincinnati, came about 2:30 p.m. We share our concern that if we don't get some assistance one or all of us might get very ill. They go to the supervisor and suggest that if medical is not going to act, then we should be transported to a hospital. Going to a hospital for a bowel program might seem extreme, but after five days, impaction is a real possibility. To our amazement, Mike is taken down to medical and then to the hospital. A raised toilet seat is borrowed from Good Samaritan Hospital. We are finally allowed to take our medications which are brought in from the outside. Monday, May 26 Memorial Day — a quiet day, a day for reflection. If non-disabled prisoners were prevented from relieving themselves for five days, it would be considered torture. Equality is as much a farce in jail as it is out of jail, maybe more so. Cincinnati's judicial and penal systems obviously feel it is fine to use a person's disability as a means of punishing that person. Documented omissions which place disabled people in potentially life-threatening situations don't raise an eyebrow, even from the defenders of justice or the media. Reports that the jail is well-equipped to handle our needs but that we will simply be “less than comfortable" go unchallenged. The fact that we have two people who care, who spend some time and resolve our problem, only highlights the injustice to those who do not have a Joni or an Art and must suffer because of ignorance of the needs of disabled persons. Tuesday, May 27 11:30 a.m.—-The court is two blocks from the jail. They usually transport the prisoners to the court by van for security reasons. We present a problem, since the van is inaccessible. They look to a supervisor, and after a half hour the answer comes down. Let the prisoners roll to the courthouse with a deputy sheriff guarding each of us. Babs, Tisha, Reverend McCracken, Art and Vivian (friends and family) are waiting in the hall. The guards hurry us into the courtroom. The media is out in force. As we wait, we wonder what the D.A. will do. Joni enters the room and her face is blank. Rubenstein, the D.A., is his usual arrogant self. Joni states that the six days served are both punishment and deterrent. Rubenstein surprisingly agrees, but asks the court to get our statement. Had we learned our lessons? He wants us to grandstand for the cameras and to get the judge mad at us again. Instead, we suppress the urge to yell "WE WILL RlDE" and simply state we will be returning to our homes and work. Cincinnati will be only a memory. Judge Sundeman accepts the motion to mitigate. We are free. 2 p.m.—We are sitting in Skyline Chili, a local restaurant, and talking over the last six days. Needless to say much of the talk is also about Detroit, October 5-9, our next battle with APTA. Spending six days in jail makes one think about commitment. Detroit will take commitment from us all, but . . . WE WILL RIDE! PHOTO 1: A close up of a man (Mike Auberger) with shoulder length dark hair and a short beard and mustache. He is wearing a light color sweater and shirt with a collar, and the chest strap from his wheelchair is visible. He looks very serious. Caption reads: MIKE AUBERGER Back in the slammer again. PHOTO 2: At least 4 policemen standing around a manual wheelchair in which someone (Bob Kafka) is being bent forward and something weird is happening with a pole (the picture is dark and hard to make out.) Caption reads: THE AUTHOR being arrested in L.A. ADAPT (200)

ADAPT (200)

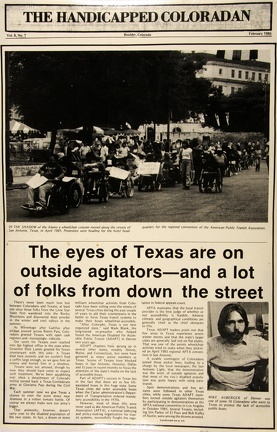

The Handicapped Coloradan, vol.8, no.7, Boulder, CO February 1986 (This article is continued in ADAPT 198 but the entire article is included here for ease of reading.) PHOTO 1: Along a street a large line of people in wheelchairs and others move past a shady park with vendors with small umbrellas over their stands. Several of the protesters carry placards in their laps, one of which reads: A PART OF NOT APART FROM. Faces are too dark to tell who is in the line. Caption reads: In the shadow of the Alamo a wheelchair column moved along the streets of San Antonio, Texas in April 1985. Protestors were heading for the hotel headquarters for the regional convention of the American Public Transit Association. PHOTO 2: Mike Auberger, with his mustache, trimmed beard and shoulder length hair looks at the camera with his intense eyes. Wearing a light colored sweater and shirt with a collar, he sits in his wheelchair which is mostly visible because of his chest strap. Caption reads: Mike Auberger of Denver was one of some 16 Coloradans who went to Texas to protest the lack of accessible public buses. [Headline] The eyes of Texas are on outside agitators -- and a lot of folks from down the street There's never been much love lost between Coloradans and Texans, at least not since those folks from the Lone Star State first wandered into the Rocky Mountains and discovered deep powder in the winter and cool valleys in the summer. As Winnebago after Cadillac after pickup poured across Raton Pass, Coloradans greeted Texans with open cash registers and - increasingly -- ridicule. Our scorn for Texans even reached into the highest office in the state when Governor Dick Lamm greeted his Texan counterpart with this joke: A Texan died here recently and we couldn't find a coffin large enough, so we gave him an enema and buried him in a shoebox. Texans were not amused, though by now they should have come to expect such treatment. We've been squabbling ever since a detachment of Colorado militia turned back a Texas Confederate army at Glorietta Pass during the Civil War. Each summer now we give Texas a chance to even the score down near Alamosa in a rotten tomato battle. OF course we always make sure our army's bigger. That animosity, however, doesn't carry over to the disabled population of the two states. In fact, a dozen or more militant wheelchair activists from Colorado have been rolling onto the streets of several Texas cities during the past couple of years to aid their counterparts in the battle to force Texas transit systems to make their buses wheelchair-accessible. "After Colorado, Texas is out best organized state," Wade Blank, the long haired ex-preacher who helped found American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) in Denver two years ago. ADAPT chapters have sprung up in several other states, notably Illinois, Maine, and Connecticut, but none have garnered as many active members as Texas. Scores of Texans have blocked buses in San Antonio, Houston, Dallas and El Paso in recent months to focus the attention of the state's media on the lack of accessible buses. Part of ADAPT's success in Texas lies in the fact that there are so few lift-equipped buses in this huge state. Some Texas cities did order accessible buses when the Carter administration's Department of Transportation ordered mandatory accessibility in the 1970s. However, most of these lifts were never used as the American Public Transit Association (APTA), a national lobbying and policy making organization for transit systems, successfully fought the regulation in federal appeals court. APTA maintains that the local transit provider is the best judge of whether or not accessibility is feasible. Adverse climatic and geographical conditions are generally cited as the chief obstacles to lifts. Texas ADAPT leaders point out that few areas in Texas experience severe winter storms and that the state's larger cities are generally laid out on flat plains. That was one of the points wheelchair activist tried to make when they picketed in April 1985 regional APTA convention in San Antonio. A sizable contingent of Coloradans joined those picket lines, leading to a charge by the local newspaper, the San Antonio Light, that the demonstration was the work of outside agitators and that most of the city's disabled population was quite happy with using paratransit. Spot demonstrations and bus seizures soon followed in other Texas cities, while some Texas ADAPT members turned outside agitators themselves by participating in demonstrations at the APTA national convention in Los Angeles in October 1985. Several Texans including Jim Parker of El Paso and Bob Kafka of Austin, were among The dozens arrested. Supporters of lifts point to cities like Seattle and Denver where most of the buses are accessible -- and increasingly free of breakdowns. Denver's Regional Transportation District (RTD) maintenance crew made a few simple changes in some of their lift systems and managed to operate experimental buses without a single breakdown. ADAPT argues that some transit providers have deliberately sabotaged their lift systems to justify removing them. Opponents of lifts argue that paratransit--usually vans that pick riders up at their residences -- is more cost effective. Supporters point to Seattle where the cost per ride on mainline buses is less than $15 a trip, which compares very favorably with the best deals offered by paratransit systems. Convenience is a major factor too, according to Mike Auberger of ADAPT-Denver, who points out that most paratransit systems require two days' advance notice and users might have to travel all day just to keep a 15 minute dental appointment. "Me, I like being able to roll down to the corner bus stop," Auberger said. ADAPT grew out of coalition of Denver disabled groups who were successful in battling RTD over wheelchair lifts. Protestors seized buses and chained themselves to railings at RTD headquarters before the battle was won. Two years ago they went national when their arch foe, APTA, held its national convention in Denver, APTA refused to allow ADAPT to present a resolution to the convention calling for mandatory accessibility until pressure was brought to bear by Denver Mayor Federico Pena, a pro-lift advocate. APTA declined, however, to vote on the issue, and ADAPT picketed the group's 1984 national convention in Washington, DC, in October. Twenty-four protestors were arrested during the demonstration, including Parker. Parker, who was joined in Washington by four other Texans, isn't through with APTA yet. When that group holds its Western Regional Convention in San Antonio April 20, Parker said they can expect almost as many demonstrators as went to Washington. "I can't think of any place in Texas where it (public transportation for the disabled) is as good as it is here in Denver -- in fact it's poor everywhere here. Dallas just decided to buy 200 or 300 new buses without lifts." The situation isn't any better in his home city of El Paso, according to Parker. "It's very poor here," he said. "There are 30 city cruisers here with lifts but the city has shown no desire to use them." Parker thinks too many people in wheelchairs are too passive. "They're not used to pushing people, but we're starting to see some changes." However, Parker points out that Texas is a very conservative state and people -- including the disabled -- are slow to change. People wishing to participate in the San Antonio demonstration should call Parker (915-564-0544) for further information. PHOTO: Two bearded, bare chested wheelchair activists (Jim Parker, and [I think] Mike Auberger) are in the foreground. Parker, his shoulder length hair tied back with a bandana, sits with his foot up on his opposite knee, hands in his fingerless gloves. The two are facing away from the camera and talking with another man who is kneeling down beside them looking up at them. Caption reads: Jim Parker (center) of ADAPT-El Paso meets with a newsman during a picket of McDonald's. Many disabled persons objected to the fast food chain's refusal to immediately retrofit all of its restaurants so that they would be accessible to wheelchair patrons. Parker is currently involved in helping organize a demonstration at the Western Regional Convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA) in San Antonio Oct. 20 - 24 [sic].![ADAPT (165) (5906 visits) [Headline] Disabled Advocates Are Rolling on Washington D.C.

For the second year in a row wheelch... ADAPT (165)](_data/i/upload/2015/11/25/20151125172839-e4b2f1f0-sm.jpg) ADAPT (165)

ADAPT (165)

[Headline] Disabled Advocates Are Rolling on Washington D.C. For the second year in a row wheelchair pickets will surround the national convention of the American Public Transit Association (APTA). Some 150 to 200 wheelchair demonstrators are expected to join the picket lines, although that number could increase dramatically by the time the four day long convention opens Sept. 30 in Washington, D.C., according to a spokesperson for the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation (ADAPT). But, unlike the convention held in Denver last year, ADAPT will not be allowed to argue the case for accessibility on the convention floor. “Gilstrap (APTA executive vice president Jack Gilstrap) told us there was no way we were going to speak this year,” Wade Blank said. Nor does Blank expect APTA to vote on a resolution introduced at the 1983 convention calling upon APTA members to purchase only lift-equipped buses. When the Carter administration mandated accessibility in the late 1970s, it was APTA that successfully fought those regulations in court, arguing that it was a judgment best left to the discretion of the local transit provider. Some cities, like Seattle and San Jose, California, and-to a lesser extent-Denver, chose to make their systems accessible, but the vast majority refused, claiming the lifts were impractical and too expensive. However, accessibility advocates say that the technology is available to design both economical and reliable lifts, but that bus manufacturers will not use it as long as there is little demand for lifts from transit providers. APTA argues that in many, if not most cases paratransit systems can offer better and more economical services to disabled riders. ADAPT maintains that isn't so, arguing that cities such as Seattle are experiencing a steady drop in the per ride cost for lift-assisted trips while paratransit costs are constant, regardless of the number of trips. At the Denver convention, APTA's position was championed by Colorado Governor Richard Lamm, who told the delegates that the country couldn't afford to equip all its buses with lifts and continue as a great nation. New York City Mayor Ed Koch is expected to take a similar tack at this year's convention. In 1983, Denver Mayor Federico Pena, who was instrumental in getting ADAPT a place on the convention agenda, supported accessibility, just as this year's host mayor, Marion Berry, is expected to do. Access/Denver will send 43 wheelchair demonstrators to Washington, although at press time they were short $4,400 of the $15,000 needed to provide them with transportation, food and lodging. Among the individuals contributing to the fund drive was Wellington Webb, an unsuccessful 1983 candidate for mayor of Denver. In addition, Denver's HAIL, Inc., will be sending five representatives. Several other cities, including Dallas, El Paso, Los Angeles, Cincinnati, Little Rock, Arkansas, Poughkeepsie, New York, and Chicago have confirmed that they will have representatives on the picket line. Boston's Disabled Liberation Front announced that it was sending eight pickets. ADAPT intends to provide a training session in confrontational politics in Washington on September 26. Ironically, one problem that demonstrators flying into Washington's Dulles International Airport will face is a lack of accessible buses between the airport and downtown Washington. "We were going to file a complaint," Blank said, "but it turns out that the Department of Transportation runs the bus system there and they say that they are the administrators, not the recipients, of federal funds, and therefor are not required to provide accessible service."![ADAPT (205) (4371 visits) [Headline] NAT HENTOFF:“No Wonder God Punished Her by Making Her Blind!”

Village Voice, March 1... ADAPT (205)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/08/20160108132553-77adf263-sm.jpg) ADAPT (205)

ADAPT (205)

[Headline] NAT HENTOFF:“No Wonder God Punished Her by Making Her Blind!” Village Voice, March 18, 1986, page unknown. PHOTO in center of page. Photo credit, DAVID STONE/MAINSTREAM: MAGAZINE OF THE ABLE-DISABLED: A group of police officers in dark short sleeved uniforms standing and looking at one another. On the floor at their feet, a man in white clothes (Chris Hronis) lies on his side arms behind his back, apparently handcuffed. Through the legs of the officers you can see someone else (Edith Harris) sitting on the floor also apparently handcuffed. At the edges of the frame you can see a couple of people's faces and at the bottom, the back of someone's head. Above the picture is a text box that reads: "I am tired of being closed away." Photo Caption reads: Disabled activists commit civil disobedience in Las Angeles to make public transit accessible: “We will ride." [Italicized] New vocabulary must be developed. Racism and sexism are words known to every schoolchild, but there is no word to describe bigotry against persons with disabilities. [End italicized] – Lisa Blumberg, Hartford Courant, June 24, I985 [Italicized]... it is absolutely essential to understand that the pain and "tragedy" of living with a disability in our culture, such as it is, derives primarily from the pain and humiliation of discrimination, oppression, and anti-disability attitudes, not from the disability itself. [End italicized] — Michelle Fine and Adrienne Asch, Carasa News, Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, June/July 1984 [Italicized] Public transportation is a tax-supported system. The handicapped pay taxes. It's as simple as that. How would the average taxpayer feel if he was denied access to a facility he paid for? [End italicized] – Wade Blank, a founder of and organizer for ADAPT (American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation), Denver Post, October 6, 1985 In the spring of 1982, a woman in a wheelchair went into a clothing store in the Bronx and was told by the guard that he was required by store policy to turn away people with wheelchairs. Shs wrote a letter of complaint to the head of the chain and received an apology, along with a $50 gift certificate. Off she went to cash in the certificate, and guess what happened? That's right. A guard turned her away from the store. The woman sued; the store settled the case by giving her a check for $10,300. I had been about to write that a disabled lawyer had handled her case, but he — Kipp Elliott Watson—corrected me. “I am a lawyer with a disability," he said. In Jim Johnson's "Shop 'Talk" column in the February 22, 1986, Editor & Publisher, there is a guide for copy editors and reporters concerning accuracy of language in stories about those with disabilities. It was put together by more than 50 national disability organizations. One illustration: “Perhaps the most offensive term to disabled people is ‘wheelchair-bound' or ‘confined to a wheelchair.’ Disabled people don't sleep in their wheelchairs, they sleep in bed. Call them 'wheelchair users.'" Also, "labeling of groups should be avoided. Say ‘people who are deaf' or 'people with arthritis’ rather than ‘the deaf' or ‘the arthritic.’ . . . One of the problems with eliminating insensitive terms is the, lack of a clear policy that reporters and editors can follow. A reporter cannot change a paper's policy by himself. The first time a reporter writes 'person who is arthritic,’ a copy editor is sure to change it to ‘an arthritic’ to save words.” And I would particularly recommend the next correction to the vast majority of the reporters and editorial writers who have covered Baby Doe cases: “Afflicted [unintelligible] a negative term that suggests hopelessness. Use disabled. Also to be avoided are deformed and invalid." The guide is especially useful because more and more of those with disabilities are going to be making news-in–lawsuits, individual acts of resistance against discrimination, and in collective demonstrations. For instance, in Los Angeles last October, during a nonviolent direct-action protest against the American Public Transit Association (which is resisting making all its buses accessible to the handicapped), there was this report by George Stein in the October 7 Los Angeles-Times: “During the procession, 131 wheelchairs, stretching more than a block, carried people with disabilities ranging from spina bifida, cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophy to snapped spinal cords, congenital defects and post-polio paralysis. “Many had the withered limbs and lack of body control that the more fortunate usually try not to stare at. “But not Sunday. Motorists slowed to watch the sight. Some honked in support. One of the demonstrators was Bob Kafka, a spokesman for ADAPT (American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit) "This is beautiful,” Kafka said as he wheeled along “I am tired of being closed away." Carolyn Earl, who uses a wheelchair, tried to make a reservation at the Harrison Hotel in Oakland, California. The clerk wouldn't take an advance deposit. Suppose there's a fire, he said. The hotel would be liable. But call back, he said. She did. Ain't that a shame, there are no rooms with baths, and she'd asked for a room with a bath. Okay, the woman said, I’ll take a room without a bath. The clerk said that for her, there were no rooms, period. Just like it used to be with blacks and Jews. It happens, however, that according to Section 54.1 of California's Civil Code, it is as unlawful to discriminate in public accommodations against people with disabilities as it is to exclude racial and ethnic minorities. Carolyn Earl went to court. In December 1984, the hotel agreed to pay her damages and to sign an agreement pledging never again to refuse lodging to anyone who is disabled. In Louisville last fall, Steve and Nadine Jacobson, who are blind, were on trial. The charge: disorderly conduct. On July 7, they had been sitting in exit-row seats on United Airlines Flight 869 to Minneapolis, where they live. Airline personnel and security employees from Standford airport ordered the Jacobsons to get out of those seats. In the event of an emergency, the Jacobsons were told, they, being blind, could jeopardize their own safety and that of others. The rationale for the policy, it came out at the trial, was a “test” some time back during which – now get this – sighted people were blindfolded two hours before a mock evacuation and it turned out that these “blind” people had trouble opening emergency exit doors as well as dealing with other evacuation procedures. On the basis of a test that used fake blind people to find out how real blind people might act, the Federal Aviation Administration—long known for its stunning brilliance—issued an advisory circular suggesting to airlines that they keep blind folks out of those emergency exit rows. As they were trying to get the Jacobsons to move, United Airlines personnel kept insisting that a "Federal regulation" said they had to get out of those seats. The Jacobsons, however, had just come from a convention at which that very advisory circular had been discussed. They knew there was no rule. And so they sat. And sat. Irritated passengers offered to trade seats with them. Another yelled that the Jacobsons were holding everybody else up. "How can you be so selfish?" And another, speaking from the heart, pointed to Nadine Jacobson, and said to a neighbor: “No wonder God punished her by making her blind!" Eventually, the Jacobsons were removed from the plane and charged with disorderly conduct—not with violating the alleged “Federal regulation." At the trial, Steve Jacobson told the jury: “All through my life, there were things I was told I couldn't do because I was blind. In college, they said I couldn't take math." (Mr. Jacobson is a computer analyst for 3M.) He went on to say that he kept ignoring all the advice about all the things he couldn't do because he was blind. “I just had to go on," he said. Where he works, he was told not to use the escalator. He could get hurt. He uses the escalator. That day at the airport, “To move from my seat would reinforce all that I've worked not to have happen. To move would say to the other people on the plane that I am less capable than any sighted person to open that emergency door. And that isn't. the case. It just isn't.” As for Nadine Jacobson: “I was scared. I had never been arrested before. I felt really bad that people were angry and upset, and that the plane was being delayed." But still she wouldn't move. “Many times people make assumptions about what we [blind people] can do and can't do. I knew that if I moved from that seat, everyone would think that anyone else was more competent than me. It's an issue of self-respect. I'm a citizen of this country, and a blind person, and I feel I have a right to travel in this country, and if I get assigned a seat, I have a right to sit there." Would the jury have been convinced solely by what the Jacobsons said? I don't know. But I expect they listened with much interest to testimony by Mark D. Warriner of Frontier Airlines, who said his company had stopped discriminating against blind people as a result of a March 1985 evacuation drill by World Airways, which showed that blind people—real blind people—got out during an emergency faster than sighted passengers. The Jacobsons were acquitted. The verdict, said Nadine Jacobson, was “a step forward for blind people all over the country." Footnote: None of the police officers or the security personnel involved in arresting the Jacobsons would give them their names. Without the names, the Jacobsons could never identify them, ho-ho. But an attorney sitting in front of the Jacobsons on the plane handed them a piece of paper with one of the names, and that led to others being revealed. The stories about the Jacobsona and the woman trying to get a hotel room originally appeared in The Disability Rag in somewhat different form. There is nothing like that paper in the whole country. It covers the whole disability rights spectrum—from what‘s happening in the courts to the directions being taken by groups of nonviolent resisters. It publishes memoirs, jeremiads, parodies, and material for which there is no category. It is the liveliest publication I know. It has grace and beauty and fury. It costs $9 a year, from The Disability Rag, Box 145, Louisville, Kentucky 40201. You have a choice of print, cassette tape, or large-print edition. We shall be getting back to public transit, along with education, jobs, and stereotypes of people with disabilities in movies and television as well as in print. The importance of access to buses and other forms of transit has been distilled by Wade Blank of ADAPT: “Jobs and education don't mean much if you can't get a bus to take you there. Accessibility to public transportation—moving from one place to another—should be a right, not just a consumer service." Recently, Wade Blank was telling me how, because of ADAPT and the pressure it keeps putting on, 78 per cent of the buses in Denver, where ADAPT is based, are now accessible. Soon, with 200 new buses on order, all of them with lifts, people with disabilities will be able to ride 90 per cent of the Denver buses. Already, Blank said, this access means a lot. “I know a man with cerebral palsy," Blank continued. “He has no use of his legs or arms. He can't speak. But now, with the buses accessible, he can ride around and see the sights and come to our offices. He can move where and when he wants to in the Denver community." He's no longer closed away. In Dallas, Kataryn Thomas, 57, was arrested last month during an ADAPT demonstration against the recalcitrant Dallas Area Rapid Transit Authority. She was born with spina bifida, uses a wheelchair, has worked as a receptionist, and when she was busted, a bright orange flag connected to the back of her chair fluttered in the breeze. The words on it were: “Free Spirit." “l don't have to climb any mountains," Kataryn Thomas told the Dallas Times Herald. “I just want to ride the public transit.”