- JezikAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Domov / Albumi / Oznake blocking a bus + handcuffed

+ handcuffed + Jim Parker

+ Jim Parker 2

2

ADAPT (224)

ADAPT (224)

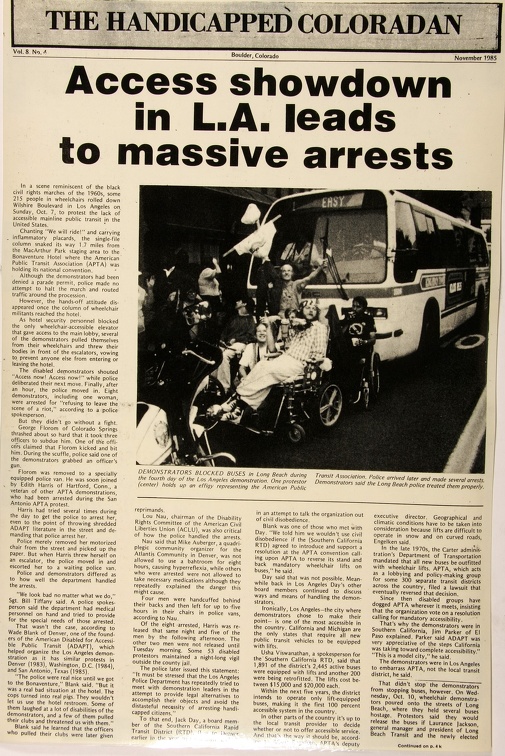

THE HANDICAPPED COLORADAN Vol. 8, No. 4, Boulder, Colorado, November 1985 [This article continues in ADAPT 115 but the story is included here in its entirety for easier reading.] PHOTO on center-right of the page and shows several people in wheelchairs (including Larry Ruiz looking away on left, as you face the bus, and George Florum on right in black ADAPT T-shirt holding a coffee and a cigarette) in front of a large bus. One person stands in front of the bus holding a scarecrow-like effigy of a person in one hand and something else in the other. A person in a white shirt is seated in the driver's seat. Another person similarly dressed is standing next to him. Above them behind the windshield is a destination type sign reading “EASY.” Caption: DEMONSTRATORS BLOCKED BUSES in Long Beach during the fourth day of the Los Angeles demonstration. One protestor (center) holds up an effigy representing the American Public Transit Association. Police arrived later and made several arrests. Demonstrators said the Long Beach police treated them properly. [Headline] Access showdown in L.A. Leads to massive arrests In a scene reminiscent of the black civil rights marches of the 1960s, some 215 people in wheelchairs rolled down Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles on Sunday, Oct. 7, to protest the lack of accessible mainline public transit in the United States. ' Chanting "We will ride!" and carrying inflammatory placards, the single-file column snaked its way 1.7 miles from the MacArthur Park staging area to the Bonaventure Hotel where the American Public Transit Association (APTA) was holding its national convention. Although the demonstrators had been denied a parade permit, police made no attempt to halt the march and routed traffic around the procession. However, the hands-off attitude disappeared once the column of wheelchair militants reached the hotel. As hotel security personnel blocked the only wheelchair-accessible elevator that gave access to the main lobby, several of the demonstrators pulled themselves from their wheelchairs and threw their bodies in front of the escalators, vowing to prevent anyone else from entering or leaving the hotel. The disabled demonstrators shouted "Access now! Access now!" while police deliberated their next move. Finally, after an hour, the police moved in. Eight demonstrators, including one woman, were arrested for “refusing to leave the scene of a riot," according to a police spokesperson. But they didn't go without a fight. George Florom of Colorado Springs thrashed about so hard that it took three officers to subdue him. One of the officers claimed that Florom kicked and bit him, During the scuffle, police said one of the demonstrators grabbed an officer's gun. Florom was removed to a specially equipped police van. He was soon joined by Edith Harris of Hartford, Conn, a veteran of other APTA demonstrations, who had been arrested during the San Antonio APTA protest. Harris had tried several times during the day to get the police to arrest her, even to the point of throwing shredded ADAPT literature in the street and demanding that police arrest her. Police merely removed her motorized chair from the street and picked up the paper, But when Harris threw herself on an escalator, the police moved in and escorted her to a waiting police van. Police and demonstrators differed as to how well the department handled the arrests. "We look bad no matter what we do," Sgt. Bill Tiffany said. A police spokesperson said the department had medical personnel on hand and tried to provide for the special needs of those arrested. That wasn't the case, according to Wade Blank of Denver, one of the founders of the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT), which helped organize the Los Angeles demonstration as it has similar protests in Denver (1983), Washington, D.C. (1984), and San Antonio, Texas (1985). "The police were real nice until we got to the Bonaventure," Blank said. “But it was a real bad situation at the hotel. The cops turned into real pigs. They wouldn't let us use the hotel restroom. Some of them laughed at a lot of disabilities of the demonstrators, and a few of them pulled their clubs and threatened us with them." Blank said he learned that the officers who pulled their clubs were later given reprimands. Lou Nau, chairman of the Disability Rights Committee of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), was also critical of how the police handled the arrests. Nau said that Mike Auberger, a quadriplegic community organizer for the Atlantis Community in Denver, was not allowed to use a bathroom for eight hours, causing hyperreflexia, while others who were arrested were not allowed to take necessary medications although they repeatedly explained the danger this might cause. Four men were handcuffed behind their backs and then left for up to five hours in their chairs in police vans, according to Nau. Of the eight arrested, Harris was released that same night and five of the men by the following afternoon. The other two men were not released until Tuesday morning. Some 53 disabled protestors maintained a night-long vigil outside the county jail. The police later issued this statement: “It must be stressed that the Los Angeles Police Department has repeatedly tried to meet with demonstration leaders in the attempt to provide legal alternatives to accomplish their objectives and avoid the distasteful necessity of arresting handicapped citizens." To that end, Jack Day, a board member of the Southern California Rapid Transit District (RTD flew to Denver earlier in the year to [print completely faded] in an attempt to talk the organization out of civil disobedience. Blank was one of those who met with Day. "We told him we wouldn't use civil disobedience if the (Southern California RTD) agreed to introduce and support a resolution at the APTA convention calling upon APTA to reverse its stand and back mandatory wheelchair lifts on buses," he said. Day said that was not possible. Meanwhile back in Los Angeles Day's other board members continued to discuss ways and means of handling the demonstrators. Ironically, Los Angeles — the city where demonstrators chose to make their point - is one of the most accessible in the country. California and Michigan are the only states that require all new public transit vehicles to be equipped with lifts. Usha Viswanathan, a spokesperson for the Southern California RTD, said that 1,891 of the district‘s 2,445 active buses were equipped with lifts and another 200 were being retrofitted. The lifts cost between $15,000 and $20,000 each. Within the next five years, the district intends to operate only lift-equipped buses, making it the first 100 percent accessible system in the country. In other parts of the country it's Up to the local transit provider to decide whether or not to offer accessible service. And that's the way it should bee, according Albert Engelken, APTA's deputy executive director. Geographical and climatic conditions have to be taken into consideration because lifts are difficult to operate in snow and on curved roads, Engelken said. In the late 1970s, the Carter administration's Department of Transportation mandated that all new buses be outfitted with wheelchair lifts. APTA, which acts as a lobbying and policy-making group for some 300 separate transit districts across the country, filed a lawsuit that eventually reversed that decision. Since then disabled groups have dogged APTA wherever it meets, insisting that the organization vote on a resolution calling for mandatory accessibility. That‘s why the demonstrators were in Southern California, Jim Parker of El Paso explained. Parker said ADAPT was very appreciative of the steps California was taking toward complete accessibility.” "This is a model city," he said. The demonstrators were in Los Angeles to embarrass APTA, not the local transit district, he said. That didn't stop the demonstrators from stopping buses, however. On Wednesday, Oct. 10, wheelchair demonstrators poured onto the streets of Long Beach, where they held several buses hostage. Protestors said they would release the buses if Laurance Jackson, general manager and president of Long Beach Transit and the newly elected president of APTA, would meet with them. A spokesperson for Jackson said that would be impossible, as Jackson had other commitments at the convention and the protestors had come unannounced. Before the day was done, police issued 33 misdemeanor citations for failure to disperse and arrested l6 protestors, all of whom were later released on their own recognizance. Blank said that the Long Beach police acted appropriately under the circumstances. Long Beach had been the scene of another confrontation earlier that same week. On Monday, 26 wheelchair demonstrators staged a roll-in at the office of U.S Rep.Glen Anderson (D-Long Beach), who is chairman of the House Transportation Committee. Anderson, who had been expected in his office that day, had been detained in Washington due to a heavy work load. The congressman later issued a statement pointing out that he had consistently voted to support accessible systems. Anderson blamed the Reagan administration, not Congress, for overturning a "requirement that the handicapped be given full accessibility to public transit." Most of the demonstrators agreed with that assessment. Blank and Parker compared APTA to the Klu Klux Klan and called upon its individual members either to fire its executive board, including executive vice president Jack Gilstrap, a longtime foe of mandatory accessibility, or to pull out and form a new national transit organization. A Gilstrap aide said he had no intention of resigning. Blank said Gilstrap and the rest of the APTA membership could expect to see them again when the organization holds its next national convention in Detroit in 1986. ADAPT plans similar tactics, since Michigan, like California, has already opted for total accessibility. "It's a question of civil rights," Blank said." And it's a national issue. Wherever they go, you can expect to find us." 3 photos filling the top three-quarters of the page. Photo 1: A man (George Florum) in a manual wheelchair wearing a black no-steps ADAPT T-shirt is loaded onto a lift of some type of vehicle by three beefy police officers Caption: GEORGE FLOROM OF of Colorado Springs is arrested for blocking buses in Long Beach. Photo 2: A dark shot of a man in a white T-shirt (Chris Hronis) being pulled upward by several sets of hands. Caption: CHRIS HONIS [sic], a California ADAPT member, is arrested at the Bonaventure Hotel. Photo 3: a couple of small groups of protesters in wheelchairs and standing, are in front of one bus and beside another, while police stand nearby. Caption: ACTIVISTS hold a bus captive in Long Beach. To the left of photo 3 is an ADAPT "we will ride" logo with the wheelchair access guy and an equal sign in the big wheel. ADAPT (196)

ADAPT (196)

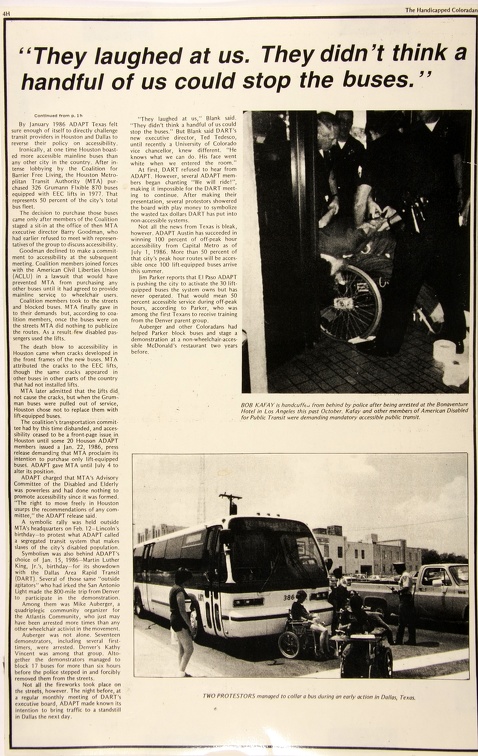

The Handicapped Coloradan PHOTO 1: Four police officer surround a man (Bob Kafka) in a manual wheelchair. Two are holding his arms behind his back, forcing his head and shoulders toward the ground as he is twisted in his wheelchair. Another officer is putting handcuffs on one of his wrists. Caption reads: BOB KAFAY [sic] is handcuffed from behind by police after being arrested at the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles this past October. Kafay and other members of American Disabled for Public Transit were demanding mandatory accessible public transit. PHOTO 2: A woman in a power wheelchair, sits in the middle of the front of the bus, stopping it in the street. Someone is standing at the left front corner of the bus beside another person in a wheelchair [possibly Larry Ruiz]. In front of this group another wheelchair user with a lap board sits in the middle of the street. On the side of the road an officer with a radio is standing, and on the near side of the bus a woman also stands and watches. All the faces are in shadow so it is hard to tell who anyone is. Caption reads: TWO PROTESTORS managed to collar a bus during an early action In Dallas, Texas. "The laughed at us. They didn't think a handful of us could stop the buses." continued from p. 16? By January 1986 ADAPT Texas felt sure enough of itself to directly challenge transit providers in Houston and Dallas to reverse their policy on accessibility. Ironically, at one time Houston boasted more accessible mainline buses than any other city in the country. After intense lobbying by the Coalition for Barrier Free Living, the Houston Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) purchased 326 Grumman Flxible 870 buses equipped with EEC lifts in 1977. That represents 50 percent of the city's total bus fleet. The decision to purchase those buses came only after members of the Coalition staged a sit-in at the office of then MTA executive director Barry Goodman, who had earlier refused to meet with representatives of the group to discuss accessibility. Goodman declined to make a commitment to accessibility at the subsequent meeting. Coalition members joined forces with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in a lawsuit that would have prevented MTA from purchasing any other buses until it had agreed to provide mainline service to wheelchair users. Coalition members took to the streets and blocked buses. MTA finally gave in to their demands but, according to coalition members, once the buses were on the streets MTA did nothing to publicize the routes. As a result few disabled passengers used the lifts. The death blow to accessibility in Houston came when cracks developed in the front frames of the new buses. MTA attributed the cracks to the EEC lifts, though the same cracks appeared in other buses in other parts of the country that had not installed lifts. MTA later admitted that the lifts did not cause the cracks, but when the Grumman buses were pulled out of service, Houston chose not to replace them with lift-equipped buses. The coalition's transportation committee had by this time disbanded, and accessibility ceased to be a front-page issue in Houston until some 20 Houston ADAPT members issued a Jan. 22, 1986, press release demanding that MTA proclaim its intention to purchase only lift-equipped buses. ADAPT gave MTA until July 4 to alter its position. ADAPT charged that MTA's Advisory Committee of the Disabled and Elderly was powerless and had done nothing to promote accessibility since it was formed. "The right to move freely in Houston usurps the recommendations of any committee," the ADAPT release said. A symbolic rally was held outside MTA's headquarters on Feb. l2 — Lincoln's birthday — to protest what ADAPT called a segregated transit system that makes slaves of the city's disabled population. Symbolism was also behind ADAPT's choice of Jan. l5, l986 Martin Luther King, ]r.'s, birthday — for its showdown with the Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART). Several of those same "outside agitators” who had irked the San Antonio Light made the 800-mile trip from Denver to participate in the demonstration. Among them was Mike Auberger, a quadriplegic community organizer for the Atlantis Community, who just may have been arrested more times than any other wheelchair activist in the movement. Auberger was not alone. Seventeen demonstrators, including several first-timers, were arrested. Denver's Kathy Vincent was among that group. Altogether the demonstrators managed to block l7 buses for more than six hours before the police stepped in and forcibly removed them from the streets. Not all the fireworks took place on the streets, however. The night before, at a regular monthly meeting of DART's executive board, ADAPT made known its intention to bring traffic to a standstill in Dallas the next day. "They laughed at us," Blank said. "They didn't think a handful of us could stop the buses." But Blank said DART's new executive director, Ted Tedesco, until recently a University of Colorado vice chancellor, knew different. “He knows what we can do. His face went white when we entered the room." At first, DART refused to hear from ADAPT. However, several ADAPT members began chanting "We will ride!", making it impossible for the DART meeting to continue. After making their presentation, several protestors showered the board with play money to symbolize the wasted tax dollars DART has put into non-accessible systems. Not all the news from Texas is bleak, however. ADAPT Austin has succeeded in winning 100 percent of off-peak hour accessibility from Capital Metro as of July 1, 1986. More than 50 percent of that city's peak hour routes will be accessible once l00 lift-equipped buses arrive this summer. Jim Parker reports that El Paso ADAPT is pushing the city to activate the 30 lift-quipped buses the system owns but has never operated. That would mean 50 percent accessible service during off-peak hours, according to Parker, who was among the first Texans to receive training from the Denver parent group. Auberger and other Coloradans had helped Parker block buses and stage a demonstration at a non-wheelchair-accessible McDonald's restaurant two years before.