- Ordre de triPar défaut

Titre de la photo, A → Z

Titre de la photo, Z → A

Date de création, récent → ancien

Date de création, ancien → récent

Date d'ajout, récent → ancien

Date d'ajout, ancien → récent

✔ Note, haute → basse

Note, basse → haute

Nombre de visites, élevé → faible

Nombre de visites, faible → élevé - LangueAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Accueil / Albums / Tags protests + Seattle Metro

+ Seattle Metro + physically handicapped

+ physically handicapped 1

1

ADAPT (148)

ADAPT (148)

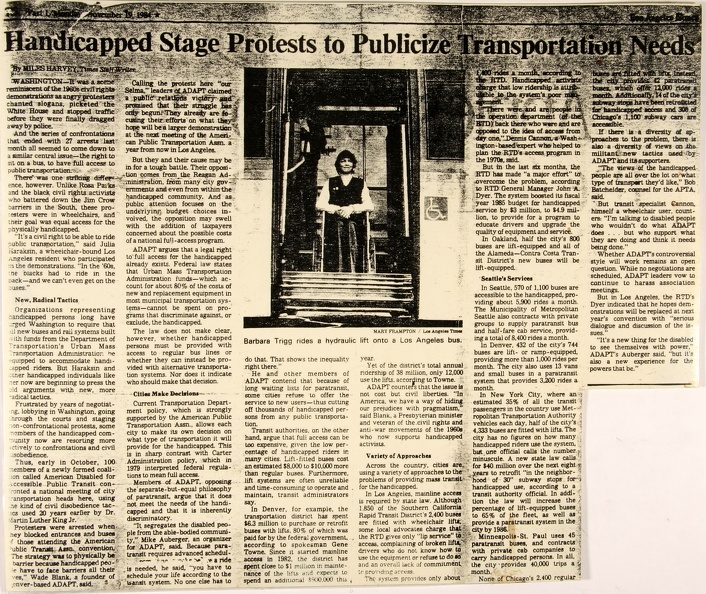

Name of newspaper illegible Los Angeles Times? November 19,1984 Handicapped Stage Protests to Publicize Transportation Needs by Miles Harvey, Times Staff Writer PHOTO: Mary Frampton / Los Angeles Times A tidy looking woman in pants and a vest, with a slight smile on her face, sits in a manual wheelchair on a bus. She is sitting in the accessible doorway, the access symbol visible on the side of the doorway. Below and beneath her is a metal panel, like the barrier on some lifts that keeps the person from rolling off the front of the lift. Caption reads: Barbara Trigg rides a hydraulic lift onto a Los Angeles bus. Article reads: Washington -- It was a scene reminiscent of the 1960s civil rights demonstrations as angry protesters chanted slogans, picketed the White House and stopped traffic before they were finally dragged away by police. And the series of confrontations that ended with 27 arrests last month seemed to come down to a similar central issue— the right to sit on a bus, to have full access to public transportation. There was one striking difference, however. Unlike Rosa Parks and the black civil rights activist who battered down the Jim Crow barriers in the South, these protesters were in wheelchairs, and their goal was equal access for the physically handicapped. “It's a civil right to be able to ride public transportation," said Julia Haraksin, a wheelchair-bound Los Angeles resident who participated in the demonstrations. “In the ‘60s, the blacks had to ride in the back—and we can't even get on the buses." New, Radical Tactics Organizations representing handicapped persons long have urged Washington to require that new buses and rail systems built with funds from the Department of Transportation's Urban Mass Transportation Administration be equipped to accommodate handicapped riders. But Haraksin and other handicapped individuals like her now are beginning to press the old arguments with new, more radical tactics. Frustrated by years of negotiating, lobbying in Washington, going through the courts and staging non-confrontational protests, some members of the handicapped community now are resorting more actively to confrontations and civil disobedience. Thus, early in October, 100 members of a newly formed coalition called American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit confronted a national meeting of city transportation heads here, using the kind of civil disobedience tactics used 30 years earlier by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Protesters were arrested when they blocked entrances and buses of those attending the American Public Transit Assn. convention. The strategy was to physically be a barrier because handicapped people have to face barriers all their lives," Wade Blank, a founder of Denver-based ADAPT said. Calling the protests here " Selma," leaders of ADAPT claimed victory and promised that their struggle has only begun. They already are focusing their efforts on what they hope will be a larger demonstration at the next meeting of the American Public Transportation Assn. a year from now in Los Angeles. But they and their cause may be in for a tough battle. Their opposition comes from the Reagan Administration, from many city governments and even from within the handicapped community. And as public attention focuses on the underlying budget choices involved, the opposition may swell with the addition of taxpayers concerned about the possible costs of a national full-access program. ADAPT argues that a legal right to full access for the handicapped already exists. Federal law states that Urban Mass Transportation Administration funds — which account for about 80% of the costs of new and replacement equipment in most municipal transportation systems—cannot be spent on programs that discriminate against, or exclude, the handicapped. The law does not make clear, however, whether handicapped persons must be provided with access to regular bus lines or whether they can instead be provided with alternative transportation systems. Nor does it indicate who should make that decision. Cities Make Decisions Current Transportation Department policy, which is strongly supported by the American Public Transportation Assn., allows each city to make its own decision on what type of transportation it will provide for the handicapped. This is in sharp contrast with Carter Administration policy, which in 1979 interpreted federal regulation to mean full access. Members of ADAPT, opposing the separate-but-equal philosophy of paratransit argue that it does not meet the needs of the handicapped and that it is inherently discriminatory. "It segregates the disabled people from the able-bodied community," Mike Auberger, an organizer for ADAPT, said. Because paratrasit requires advanced scheduling [unreadable] a ride is needed, he said, “you have to schedule your life according to the system. No one else has to do that. That shows the inequality right there." He and other members of ADAPT contend that because of long waiting lists for paratransit, some cities refuse to offer the service to new users - thus cutting off thousands of handicapped persons from any public transportation. Transit authorities, on the other hand, argue that full access can be too expensive, given the low percentage of handicapped riders in many cities. Lift-fitted buses cost an estimated $8,000 to $10,000 more than regular buses. Furthermore, lift systems are often unreliable and time-consuming to operate and maintain, transit administrators say. In Denver, for example, the transportation district has spent $63 million to purchase or retrofit buses with lifts. 80% of which was paid for by the federal government, according to spokesman Gene Towne. Since it started mainline access in 1982, the district has spent close to $1 million in maintenance of the lifts and expects to spend an additional $900,000 this year. Yet of the district's total annual ridership of 38 million, only 12,000 use the lifts, according to Towne. ADAPT counters that the issue is not cost but civil liberties. “In America we have a way of hiding, our prejudices with pragmatism," said Blank, a Presbyterian minister and veteran of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s who now supports handicapped activists. Variety of Approaches Across the country, cities are using a variety of approaches to the problems of providing mass transit for the handicapped. In Los Angeles, mainline access is required by state law. Although 1,850 of the Southern California Rapid Transit District‘s 2,400 buses are fitted with wheelchair lifts some local advocates charge that the RTD gives only "lip service" to access, complaining of broken lifts, drivers who do not know how to use the equipment or refuse to do so and an overall lack of commitment to providing access. The system provides only about 1,400 rides a month according to the RTD. Handicapped activists charge that the low ridership is attributable to the system's poor management. There were and are people in the operation department (of the RTD) back there who were and are opposed to the idea of access from day one," Dennis Cannon, a Washington-based expert who helped to plan the RTD's access program in the 1970s said. But in the last six months, the RTD has made "a major effort" to overcome the problem, according to RTD General Manager John A. Dyer. The system boosted its fiscal year 1985 budget for handicapped service by $3 million, to $4.9 million, to provide for a program to educate drivers and upgrade the quality of equipment and service. In Oakland, half the city's 800 buses are lift-equipped and all of the Alameda — Contra Costa Transit District's new buses will be lift-equipped. Seattle’s Services In Seattle, 570 of 1,100 buses are accessible to the handicapped, providing about 5,900 rides a month. The Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle also contracts with private groups to supply paratransit bus and half-fare cab service, providing a total of 8,400 rides a month in Denver. 432 of the city's 744 buses are lift- or ramp-equipped, providing more than 1,000 rides per month. The city also uses 13 vans and small buses in a paratransit system that provides 3,200 rides a month. In New York City, where an estimated 35% of all the transit passengers in the country use Metropolitan Transportation Authority vehicles each day. half of the city's 4,333 buses are fitted with lifts. The city has no figures on how many handicapped riders use the system, but one official calls the number minuscule. A new state law calls for $40 million over the next eight years to retrofit “in the neighborhood of 30" subway stops for handicapped use, according to a transit authority official. In addition the law will increase the percentage of lift-equipped buses to 65% of the fleet, as well as provide a paratransit system in the city by 1988. Minneapolis-St. Paul uses 45 paratransit buses and contracts with private cab companies to carry handicapped persons in all, the city provides 40.000 trips a month. None of Chicago's 2.400 regular buses are fitted with lifts. Instead the city provides 42 paratransit buses, which offer 12,000 rides a month. Additionally, 14 of the city's subway stops have been retrofitted for handicapped access and 300 of Chicago's 1,100 subway cars are accessible. If there is a diversity of approaches to the problem, there is also a diversity of views on the militant new tactics used by ADAPT and its supporters. The views of the handicapped people are all over the lot on what type of transport they'd like," Bob Batchelder, counsel for the APTA, said. But transit specialist Cannon, himself a wheelchair user, counters: “I'm talking to disabled people who wouldn't do what ADAPT does ... but who support what they are doing and think it needs being done." Whether ADAPT's controversial style will work remains an open question. While no negotiations are scheduled, ADAPT leaders vow to continue to harass association meetings. But in Los Angeles, the RTD's Dyer indicated that he hopes demonstrations will be replaced at next year's convention with “serious dialogue and discussion of the issues." "It’s a new thing for the disabled to see themselves with power," ADAPT's Auberger said, "but it's also a new experience for the powers that be."