- YezhAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Degemer / Rummadoù / Merkerioù Bob Kafka + local option

+ local option + arrests

+ arrests 3

3

ADAPT (354)

ADAPT (354)

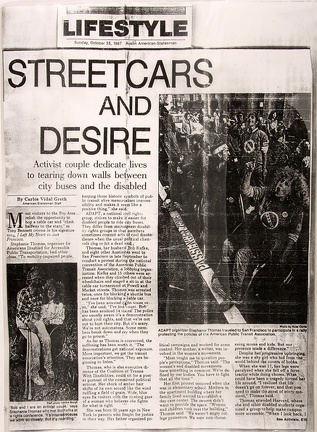

Austin American-Statesman Sunday, October 25, 1987 Lifestyle section Title: Streetcars and Desire Activist couple dedicate lives to tearing down walls between city buses and the disabled By Carlos Vidal Greth, American-Statesman Staff (This is a compilation of the article that is on ADAPT 354 and ADAPT 353. The content is all included here for easier reading.) Most visitors to the Bay Area relish the opportunity to hop a cable car and "climb halfway to the stars," as Tony Bennett croons in his signature song, I Left My Heart in San Francisco. Stephanie Thomas, organizer for Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, had other ideas. "To mobility-impaired people, keeping those historic symbols of public transit alive memorializes inaccessibility and makes it seem like a positive thing," she said. ADAPT, a national civil-rights group, strives to make it easier for disabled people to ride city buses. They differ from mainstream disability-rights groups in that members sometimes commit acts of civil disobedience when the usual political channels clog or hit a dead end. Thomas, her husband Bob Kafka, and eight other Austinites went to San Francisco in late September to conduct a protest during the national convention of the American Public Transit Association, a lobbying organization. Kafka and 15 others were arrested when they climbed out of their wheelchairs and staged a sit-in at the cable car turnaround at Powell and Market streets. Thomas was arrested twice, once for blocking a shuttle bus and once for blocking a cable car. "I've been arrested eight times or so," she said. "I've lost count. Bob has been arrested 14 times. The police are usually aware it's a demonstration about civil rights, and that we're not out to hurt their city. But it's scary. We're not automatons. Some members break down and cry when they go to prison." As far as Thomas is concerned, the suffering has been worth it. "The demonstrations got national exposure. More important, we got the transit association's attention. They are beginning to listen." Thomas, who is also executive director of the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities, could sit for a poster portrait of the committed political activist. Her shock of amber hair shifts of its own accord like the wind ruffling a field of grain. Wide, blue eyes fix visitors with the riveting gaze of a woman who believes she fights for what is right. She was born 30 years ago in New York to parents who fought for justice in their way. Her father organized political campaigns and worked for arms control. Her mother, a writer, was involved in the women's movement. "Mom taught me to question people's perceptions," Thomas said. "The women's and disabled movements have something in common: We're defined by our bodies. You have to fight that all the time." Her first protest occurred when she was in elementary school. Mothers in the apartment building where her family lived wanted to establish a day-care center. The owners didn't want to provide the space. "Women and children took over the building," Thomas said. "We weren't angry college protestors. We were non-threatening moms and kids. But our presence made a difference." Despite her progressive upbringing, she was a shy girl who hid from the world behind the covers of books. When she was 17, her legs were paralyzed when she fell off a farm tractor while doing chores. What could have been a tragedy turned her life around. "I realized that life doesn't go on forever, and that you need to make the most of every moment," Thomas said. Thomas attended Harvard, where she and other disabled students organized a group to help make campus more accessible. "When I look back, I see we were very tame,” she said. “We were polite but usually got what we asked for.” Over the years, Thomas became increasingly active in disability rights. She got involved in independent living centers, communities of disabled people supporting one another so they can live with dignity outside institutions. In the early 1980s, she joined the Austin Resources Center for Independent Living. She went to work for the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities in 1985. The 9-year-old coalition lobbies for, represents and coordinates 90 organizations (including ADAPT) concerned with disabilities, as well as the more than 2 million disabled Texans. “It is the collective voice for the disabled in Texas,” said Kaye Beneke, spokeswoman for the Texas Rehabilitation Commission. "They’re committed - the members live every day with the problems they try to solve. “Stephanie understands there’s a spectrum of political views in the coalition, which tend to be more middle-of-the-road than ADAPT. She takes responsibility for the representing of all those views. But don’t call the coalition passive. They’ve had their way in the legislature and on the local level.” As a leader in two of Texas major disability-rights organizations, Thomas has her hands full. It helps having Bob Kafka, who broke his back in a car accident in 1973, at her side. The experienced trouble maker -- albeit trouble for a good cause -- has made a name for himself. He won the Governor’s Citation for Meritorious Service in 1986. Appropriately, Kafka met Thomas at a disability-rights conference. “Stephanie was real involved, real committed and real attractive,” he said. Sharing home and office has increased their commitment to the cause they serve- and to each other. “Bob and I are an activist couple,” Thomas said. “It’s intense because we work so closely. But it’s rewarding. It has made us an incredibly tight couple.” Thomas has to rework her concept of activism when she joined ADAPT. “Demonstrations force the public to look at disabled people in a different light,” she said. “The cripple is the epitome of powerlessness. We say we’re sorry if it scares you to look at me, but we have to live our lives.” Confrontation, however can cost allies as well as foes. This year, the Paralyzed Veterans of America severed ties with ADAPT and any organization "advocating illegal civil disobedience.” “Our charter states that we must act in accordance with the laws of the land,” said Phil Rabin, director of education. “To act otherwise would be to violate our charter. “The veterans and ADAPT members share first-hand the frustration of living in a society that is not accessible to the disabled. We don’t want to fight ADAPT. It’s a waste of precious resources to divert our energies.” Though Thomas’ group is controversial, it has achieved many of its goals. Albert Engleken, deputy executive director for the American Public Transit Association in Washington, D.C., acknowledged that ADAPT’s street theater has had some effect. In September his organization created a task force to study the issue of providing service for disabled, he said. Engelken, however is not a convert to their cause. “ADAPT wants a lift on every transit bus in the country,” Engelken said. “We believe it should be left to local transit authorities to decide how to handle transportation for disabled people. Transit officials are not robber barons. We’re paid by the public to provide the most mobility for the most people.” Thomas knows how to work within the system. Ben Gomez, director of development for Capital Metro, said ADAPT members have been effective on the Mobility Impaired Service Advisory Committee, which makes recommendations on service to the transit authority board of directors. “They’re well-organized,” Gomez said. “We don’t always agree on the approach and issues. We’ve made many of the adjustments they’ve asked for, but not always within their time frame.” The concessions have been gratifying, but Thomas has only begun to fight. “ADAPT took a dead issue änd made it hot again,” she said. For information on American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, write to ADAPT of Texas, 2810 Pearl, Austin 78705/ To learn more about the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities, call 443-8252, or write to P.O. Box 4709, Austin 78765. [curator note: addresses and phone numbers no longer valid] Staff Photo by Mike Boroff: A man (Bob Kafka) with Canadian (wrist cuff) crutches, a plaid shirt, light colored jeans and sneakers sits in the lap of a woman (Stephanie Thomas) with wild big hair and a button down shirt. She is sitting in a manual wheelchair. Caption reads: "Bob and I are an activist couple,” says Stephanie Thomas who met Bob Kafka at a rights conference. “It’s intense because we work so closely. But it’s rewarding.” Photo by Russ Curtis: A group of protesters are looking up at something over their heads and their mouths are open shouting. In the front of the picture a woman in a manual wheelchair (Stephanie Thomas) is sitting on a line on the pavement that reads passenger zone. She has her finger raised pointing and is wearing a t-shirt with the ADAPT no-steps logo. Beside her is a man (Jim Parker) with a headband looking back over his shoulder, beside him another man in a wheelchair. Behind Jim stands a woman (Babs Johnson) with her arms by her sides and her mouth open yelling. Behind her a line of other protesters is arriving. Caption reads: ADAPT organizer Stephanie Thomas traveled to San Francisco to participate in a rally protesting the policies of the American Public Transit Association. ADAPT (217)

ADAPT (217)

Mainstream magazine, no date listed, p.9. Attachment IV [Story continues in ADAPT 211 and then ADAPT 210 but is included here in its entirety for easier reading. Story seems to be cut off at the end.] Photo bottom half of page: Image of people marching down the center of the street, some carrying signs, one with the ADAPT logo and another saying, “APTA OPPRESSES." Line snakes back out of sight alongside traffic in the back. Wheelchairs are lined up smartly presenting an impressive image. [Headline] ADAPT PUBLIC TRANSIT OR ELSE by Mike Ervin One of the largest civil rights marches in history by people with disabilities was held Sunday, October 7, 1985 in downtown Los Angeles to protest the American Public Transit Association (APTA)'s policy of local option transit for disabled. In response to an “invitation” by American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) to join in picketing the annual APTA convention, national leaders of the Disability Rights Movement converged at MacArthur Park to roll the 1.7 miles to the convention site at the Bonaventure Hotel. Bill Bolte of the California Association of the Physically Handicapped (CAPH) took a head count of the line of people in wheelchairs rolling single file down the middle of Wilshire Boulevard and announced that there was 215 present. The L.A. Police Department had refused to issue a parade permit to the group and had said it would not allow the long planned parade to be held on the street, but when 200 plus wheelchair users took to the pavement (no curb cuts) all the police could do was route traffic around the procession. It was an impressive sight; more than twice the number of people ADAPT had turned out for previous demonstrations at the annual conventions of APTA. As the line of people stretched more than a block in front of the posh Bonaventure Hotel where APTA was staying, the L.A. Police waited; there wasn’t much they could do except establish their presence. The protesters marched into the hotel lobby taking up most of the available space. Chants of “We will ride!" Filled the atrium below as bewildered hotel guests wondered what all this could possibly be about. The Hotel Security immediately blocked the one wheelchair accessible elevator to the main lobby. This escalated (so to speak) the confrontation, as demonstrators got out of their wheelchairs to block the escalators, saying “if you block our access, then we will block the escalators. No one will be able to use them." Meanwhile the police discussed the strategy of arresting certain people first whom they had identified as leaders. Photo: A man, Bob Kafka, sitting awkwardly, almost falling out of his manual wheelchair, apparently handcuffed behind his back. His legs are falling under the chair, and he is surrounded by four or more police officers. Article continues: Eight people, one woman and seven men, were arrested and booked without charges. The police told the media that the charge was “refusing to leave the scene of a riot.” The woman arrestee was released Sunday night, five of the men were released the following afternoon, and the last two men were released Tuesday morning after 53 disabled individuals held an all night vigil outside the county jail. On Tuesday morning, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), represented by Lou Nau, the chairman of the Disability Rights Committee of the ACLU, outlined the treatment that the arrestees faced. Four of the men were handcuffed behind their backs and left to sit in the police vehicles for up to five hours. Mike Auburger, a quadriplegic, was not allowed to use the bathroom for eight hours, causing hyperreflexia. Individuals on sustaining medication repeatedly asked for their medication, but never received it. Nau said to permit no bail for misdemeanor offenses is clearly against the law. Although APTA tried to discredit the protestors as a “small militant group of outsiders," they represented a wide spectrum of the Disability Rights Movement including Robert Funk, Executive Director of the Disability Rights and Education Defense Fund; Michael Winter, Director of the Center for Independent Living, Berkeley, CA; Judy Heumann, of the World Institute on Disability; Joe Zenzola, President, California Association of the Physically Handicapped; Peg Nosek, of Independent Living Research Utilization Project, Houston, TX; Catherine Johns, President of The Association on Handicapped Student Service Programs in Post-Secondary Education; John Chapples, Department of Rehabilitation, Boston, MA; Mark Johnson, Department of Rehabilitation, Denver, CO; Marco Bristo, Director, Access Living, Chicago, IL; Harlan Hahn, Professor, University of Southern California; and Don Galloway, D.C. Center for Independent Living. The following days saw many more protests in the Los Angeles area. On Wednesday, about 50 individuals arrived at the office of Larry Jackson, Director of the Long Beach Transit Authority, who is the incoming President of APTA. After being denied a meeting with him, they went out into the streets. The police gave them l0 minutes to disburse or be arrested. When no one moved, the police proceeded to arrest the protestors and take them to jail in 6 dial-a-ride vans. These individuals were booked and then released, as it was not possible for the Long Beach Police Department to accommodate so many disabled people. The passers-by had many different reactions to what they were experiencing; some were mad at being detained, some joined in. One man gave protestors a banner which read “help” and proceeded to distribute little American.... [rest of the article is not available.] Three photos. Photo 1: At the bottom of an escalator a mass of people in wheelchairs gathered together, Julie Farrar in the center, holding a picket sign: “APTA DESTROYED 504”. Photo 2: A man, Chris Hronis, lying on his side on the floor, handcuffed behind his back, surrounded by four or more police standing over him. Photo 3: Through the window of a van you see two man, Chris Hronis in back and Bob Kafka in front of him, sitting in wheelchairs. Both are handcuffed behind their backs. ADAPT (228)

ADAPT (228)

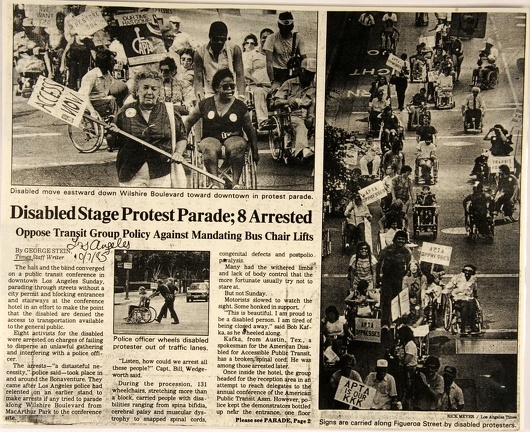

Los Angeles Times 10/7/85 [This article continues on ADAPT 227 but the entire text of the story is included here for easier reading,] 3 photos by Rick Meyer/Los Angles Times: photo 1 is of a section of the march with men and women of various ethnic backgrounds and disabilities walking, rolling and pushing others' chairs. There is a sense of energy in the group and many wear buttons and carry signs reading "Access Now", "Restore 504", and "Our Time has Come -- CAPH." Caption reads: Disabled move eastward down Wilshire Boulevard toward downtown in protest parade. Photo 2 is another picture of the march, taken from above. The crowd is loosely organized, many in the front are looking up and smiling. There are children with disabilities, people in neckties, people with headbands. In the crowd you can see Bill Bolte, Bob Kafka, Gil Casarez among many others. Some carry signs on sticks reading "APTA oppresses", as well as "Transit for All" and one about ADAPT. Caption reads: Signs are carried along Figueroa Street by disabled protesters. Photo 3 (much smaller) is of a police officer pushing a man in a manual wheelchair (Jim Parker) to the side of the street while another officer seems to be stopping a car. Caption reads: Police officer wheels disabled protester out of traffic lanes. [Headline] Disabled Stage Protest Parade; 8 Arrested Oppose Transit Group Policy Against Mandating Bus Chair Lifts By GEORGE STEIN Times Staff Writer The halt and the blind converged on a public transit conference in downtown Los Angeles Sunday, parading through streets without a city permit and blocking entrances and stairways at the conference hotel in an effort to make the point that the disabled are denied the access to transportation available to the general public. Eight activists for the disabled were arrested on charges of failing to disperse an unlawful gathering and intefering with a police officer. The arrests —“a distasteful necessity," police said -- took place in and around the Bonaventure. They came after Los Angeles police had relented to an earlier stand to make arrests if any tried to parade along Wilshire Boulevard from MacArthur Park to the conference. “Listen, how could we arrest all these people?" Capt. Bill Wedgeworth said. During the procession, 131 wheelchairs, stretching more than a block, carried people with disabilities ranging from spina bifidia, cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophy to snapped spinal cords, congenital defects and postpolio paralysis. Many had the withered limbs and lack of body control that the more fortunate usually try not to stare at. But not Sunday. Motorists slowed to watch the sight. Some honked in support. “This is beautiful. I am proud to be a disabled person. I am tired of being closed away," said Bob Kafka, as he wheeled along. Kafka, from Austin, Tex., a spokesman for the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, has a broken spinal cord. He was among those arrested later. Once inside the hotel, the group headed for the reception area in an attempt to reach delegates to the annual conference of the American Public Transit Assn. However, police kept the demonstrators bottled up near the entrance, one floor above the main reception area. "Access now! Access now!" the demonstrators shouted. The crowd, which came from a spectrum of disabled activist groups in and out of California, targeted the transit convention because the organization opposes a national policy mandating wheelchair lifts on buses. The American Public Transit Assn.'s position is to let each transit agency deal with access for the disabled as a local decision. In Los Angeles, the Southern California Rapid Transit District, with 2,445 buses, has wheelchair lifts on 1,691 and is retrofitting another 200. The RTD hopes to have lifts on all buses in five years, which, according to a spokesman, would probably make it the first major urban bus system to be so equipped. After the demonstrators blocked hotel escalator wells for almost an hour, Wedgeworth told them their gathering was illegal. The actual arrests were an odd orchestration of defiance and cooperation. Escalator Well George Florom, a member of the disabled group from Colorado Springs, Colo., began thrashing as police tried to remove him from an escalator well. It took three officers to subdue him. “He began kicking and trying to bite me, so he had to go," Lt Ken Colby explained. One of the demonstrators grabbed an officer's gun, police said. Florom, lay quietly once handcuffed, and police gently placed him in his wheelchair and wheeled him to a lift-equipped van that had been arranged for the occasion. Trained medical personnel also were on hand. Edith Harris of Hartford, Conn., had earlier failed in an attempt to get arrested, tearing up American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit literature and throwing it on Figueroa Street. "Arrest me,“ she screamed to ‘no avail from her motorized wheelchair. The police only moved her to the sidewalk, and an officer went back to [unreadable] trash. Her wish was granted later, after she tried to herself down one of the blocked escalators. Then she calmed down, gratefully accepting a drink of water from a police officer, while waiting for a stretcher to arrive. Unhandcuffed, sitting upright, she was placed in the van. Her wheelchair was carefully handed in after her. Taken to Station The arrestees were taken to the Central Division station for processing. The seven men were later booked at County Jail, where bail was set at $500. Harris was booked at Sybil Brand Institute. Some police worried that the department's image would suffer from Sunday's action. “We look bad, no matter what we do," Sgt. Bill Tiffany said. After the arrests, a spokesman said, “It must be stressed that the Los Angeles Police Department has repeatedly tried to meet with demonstration leaders in the attempt to provide legal alternatives to accomplish their objectives and avoid the distasteful necessity of arresting handicapped citizens.” The police were not alone in their concern. Five months before the convention, according to Mark Johnson, 34, of Westminster, Colo., an organizer for the disabled group, RTD board member Jack Day flew to Denver to try to talk the organization out of civil disobedience. Negotiations foundered on an demand by the disabled group that the RTD introduce and support a proposal that the American Public Transit Assn. reverse its stand and back mandatory wheelchair lifts on buses, Johnson said. He said the disabled activists will be in town through Wednesday. The American Public Transit Assn. is a lobbying and policy organization. The five-day convention began Sunday.