- LanguageAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Home / Albums / Tags Bob Kafka + blocking a bus

+ blocking a bus + Jim Parker

+ Jim Parker 2

2

ADAPT (354)

ADAPT (354)

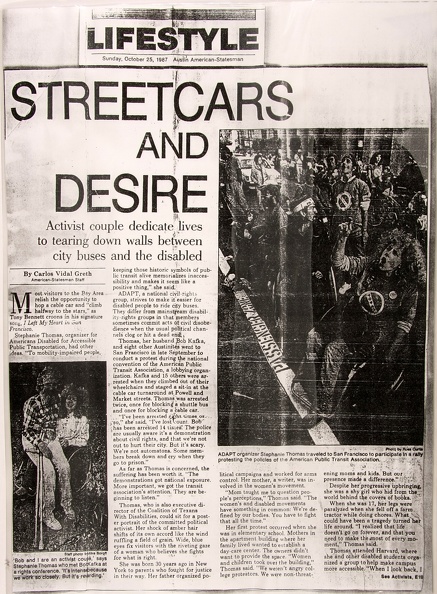

Austin American-Statesman Sunday, October 25, 1987 Lifestyle section Title: Streetcars and Desire Activist couple dedicate lives to tearing down walls between city buses and the disabled By Carlos Vidal Greth, American-Statesman Staff (This is a compilation of the article that is on ADAPT 354 and ADAPT 353. The content is all included here for easier reading.) Most visitors to the Bay Area relish the opportunity to hop a cable car and "climb halfway to the stars," as Tony Bennett croons in his signature song, I Left My Heart in San Francisco. Stephanie Thomas, organizer for Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, had other ideas. "To mobility-impaired people, keeping those historic symbols of public transit alive memorializes inaccessibility and makes it seem like a positive thing," she said. ADAPT, a national civil-rights group, strives to make it easier for disabled people to ride city buses. They differ from mainstream disability-rights groups in that members sometimes commit acts of civil disobedience when the usual political channels clog or hit a dead end. Thomas, her husband Bob Kafka, and eight other Austinites went to San Francisco in late September to conduct a protest during the national convention of the American Public Transit Association, a lobbying organization. Kafka and 15 others were arrested when they climbed out of their wheelchairs and staged a sit-in at the cable car turnaround at Powell and Market streets. Thomas was arrested twice, once for blocking a shuttle bus and once for blocking a cable car. "I've been arrested eight times or so," she said. "I've lost count. Bob has been arrested 14 times. The police are usually aware it's a demonstration about civil rights, and that we're not out to hurt their city. But it's scary. We're not automatons. Some members break down and cry when they go to prison." As far as Thomas is concerned, the suffering has been worth it. "The demonstrations got national exposure. More important, we got the transit association's attention. They are beginning to listen." Thomas, who is also executive director of the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities, could sit for a poster portrait of the committed political activist. Her shock of amber hair shifts of its own accord like the wind ruffling a field of grain. Wide, blue eyes fix visitors with the riveting gaze of a woman who believes she fights for what is right. She was born 30 years ago in New York to parents who fought for justice in their way. Her father organized political campaigns and worked for arms control. Her mother, a writer, was involved in the women's movement. "Mom taught me to question people's perceptions," Thomas said. "The women's and disabled movements have something in common: We're defined by our bodies. You have to fight that all the time." Her first protest occurred when she was in elementary school. Mothers in the apartment building where her family lived wanted to establish a day-care center. The owners didn't want to provide the space. "Women and children took over the building," Thomas said. "We weren't angry college protestors. We were non-threatening moms and kids. But our presence made a difference." Despite her progressive upbringing, she was a shy girl who hid from the world behind the covers of books. When she was 17, her legs were paralyzed when she fell off a farm tractor while doing chores. What could have been a tragedy turned her life around. "I realized that life doesn't go on forever, and that you need to make the most of every moment," Thomas said. Thomas attended Harvard, where she and other disabled students organized a group to help make campus more accessible. "When I look back, I see we were very tame,” she said. “We were polite but usually got what we asked for.” Over the years, Thomas became increasingly active in disability rights. She got involved in independent living centers, communities of disabled people supporting one another so they can live with dignity outside institutions. In the early 1980s, she joined the Austin Resources Center for Independent Living. She went to work for the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities in 1985. The 9-year-old coalition lobbies for, represents and coordinates 90 organizations (including ADAPT) concerned with disabilities, as well as the more than 2 million disabled Texans. “It is the collective voice for the disabled in Texas,” said Kaye Beneke, spokeswoman for the Texas Rehabilitation Commission. "They’re committed - the members live every day with the problems they try to solve. “Stephanie understands there’s a spectrum of political views in the coalition, which tend to be more middle-of-the-road than ADAPT. She takes responsibility for the representing of all those views. But don’t call the coalition passive. They’ve had their way in the legislature and on the local level.” As a leader in two of Texas major disability-rights organizations, Thomas has her hands full. It helps having Bob Kafka, who broke his back in a car accident in 1973, at her side. The experienced trouble maker -- albeit trouble for a good cause -- has made a name for himself. He won the Governor’s Citation for Meritorious Service in 1986. Appropriately, Kafka met Thomas at a disability-rights conference. “Stephanie was real involved, real committed and real attractive,” he said. Sharing home and office has increased their commitment to the cause they serve- and to each other. “Bob and I are an activist couple,” Thomas said. “It’s intense because we work so closely. But it’s rewarding. It has made us an incredibly tight couple.” Thomas has to rework her concept of activism when she joined ADAPT. “Demonstrations force the public to look at disabled people in a different light,” she said. “The cripple is the epitome of powerlessness. We say we’re sorry if it scares you to look at me, but we have to live our lives.” Confrontation, however can cost allies as well as foes. This year, the Paralyzed Veterans of America severed ties with ADAPT and any organization "advocating illegal civil disobedience.” “Our charter states that we must act in accordance with the laws of the land,” said Phil Rabin, director of education. “To act otherwise would be to violate our charter. “The veterans and ADAPT members share first-hand the frustration of living in a society that is not accessible to the disabled. We don’t want to fight ADAPT. It’s a waste of precious resources to divert our energies.” Though Thomas’ group is controversial, it has achieved many of its goals. Albert Engleken, deputy executive director for the American Public Transit Association in Washington, D.C., acknowledged that ADAPT’s street theater has had some effect. In September his organization created a task force to study the issue of providing service for disabled, he said. Engelken, however is not a convert to their cause. “ADAPT wants a lift on every transit bus in the country,” Engelken said. “We believe it should be left to local transit authorities to decide how to handle transportation for disabled people. Transit officials are not robber barons. We’re paid by the public to provide the most mobility for the most people.” Thomas knows how to work within the system. Ben Gomez, director of development for Capital Metro, said ADAPT members have been effective on the Mobility Impaired Service Advisory Committee, which makes recommendations on service to the transit authority board of directors. “They’re well-organized,” Gomez said. “We don’t always agree on the approach and issues. We’ve made many of the adjustments they’ve asked for, but not always within their time frame.” The concessions have been gratifying, but Thomas has only begun to fight. “ADAPT took a dead issue änd made it hot again,” she said. For information on American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, write to ADAPT of Texas, 2810 Pearl, Austin 78705/ To learn more about the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities, call 443-8252, or write to P.O. Box 4709, Austin 78765. [curator note: addresses and phone numbers no longer valid] Staff Photo by Mike Boroff: A man (Bob Kafka) with Canadian (wrist cuff) crutches, a plaid shirt, light colored jeans and sneakers sits in the lap of a woman (Stephanie Thomas) with wild big hair and a button down shirt. She is sitting in a manual wheelchair. Caption reads: "Bob and I are an activist couple,” says Stephanie Thomas who met Bob Kafka at a rights conference. “It’s intense because we work so closely. But it’s rewarding.” Photo by Russ Curtis: A group of protesters are looking up at something over their heads and their mouths are open shouting. In the front of the picture a woman in a manual wheelchair (Stephanie Thomas) is sitting on a line on the pavement that reads passenger zone. She has her finger raised pointing and is wearing a t-shirt with the ADAPT no-steps logo. Beside her is a man (Jim Parker) with a headband looking back over his shoulder, beside him another man in a wheelchair. Behind Jim stands a woman (Babs Johnson) with her arms by her sides and her mouth open yelling. Behind her a line of other protesters is arriving. Caption reads: ADAPT organizer Stephanie Thomas traveled to San Francisco to participate in a rally protesting the policies of the American Public Transit Association. ADAPT (196)

ADAPT (196)

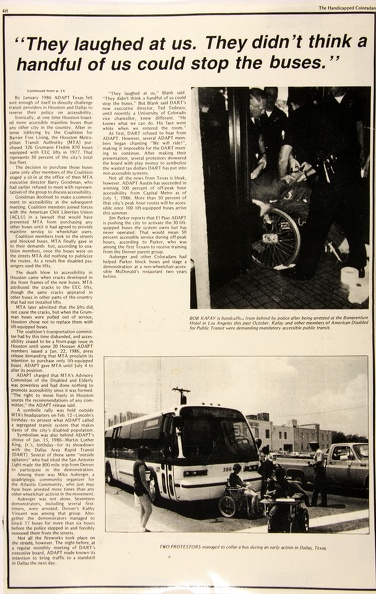

The Handicapped Coloradan PHOTO 1: Four police officer surround a man (Bob Kafka) in a manual wheelchair. Two are holding his arms behind his back, forcing his head and shoulders toward the ground as he is twisted in his wheelchair. Another officer is putting handcuffs on one of his wrists. Caption reads: BOB KAFAY [sic] is handcuffed from behind by police after being arrested at the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles this past October. Kafay and other members of American Disabled for Public Transit were demanding mandatory accessible public transit. PHOTO 2: A woman in a power wheelchair, sits in the middle of the front of the bus, stopping it in the street. Someone is standing at the left front corner of the bus beside another person in a wheelchair [possibly Larry Ruiz]. In front of this group another wheelchair user with a lap board sits in the middle of the street. On the side of the road an officer with a radio is standing, and on the near side of the bus a woman also stands and watches. All the faces are in shadow so it is hard to tell who anyone is. Caption reads: TWO PROTESTORS managed to collar a bus during an early action In Dallas, Texas. "The laughed at us. They didn't think a handful of us could stop the buses." continued from p. 16? By January 1986 ADAPT Texas felt sure enough of itself to directly challenge transit providers in Houston and Dallas to reverse their policy on accessibility. Ironically, at one time Houston boasted more accessible mainline buses than any other city in the country. After intense lobbying by the Coalition for Barrier Free Living, the Houston Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) purchased 326 Grumman Flxible 870 buses equipped with EEC lifts in 1977. That represents 50 percent of the city's total bus fleet. The decision to purchase those buses came only after members of the Coalition staged a sit-in at the office of then MTA executive director Barry Goodman, who had earlier refused to meet with representatives of the group to discuss accessibility. Goodman declined to make a commitment to accessibility at the subsequent meeting. Coalition members joined forces with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in a lawsuit that would have prevented MTA from purchasing any other buses until it had agreed to provide mainline service to wheelchair users. Coalition members took to the streets and blocked buses. MTA finally gave in to their demands but, according to coalition members, once the buses were on the streets MTA did nothing to publicize the routes. As a result few disabled passengers used the lifts. The death blow to accessibility in Houston came when cracks developed in the front frames of the new buses. MTA attributed the cracks to the EEC lifts, though the same cracks appeared in other buses in other parts of the country that had not installed lifts. MTA later admitted that the lifts did not cause the cracks, but when the Grumman buses were pulled out of service, Houston chose not to replace them with lift-equipped buses. The coalition's transportation committee had by this time disbanded, and accessibility ceased to be a front-page issue in Houston until some 20 Houston ADAPT members issued a Jan. 22, 1986, press release demanding that MTA proclaim its intention to purchase only lift-equipped buses. ADAPT gave MTA until July 4 to alter its position. ADAPT charged that MTA's Advisory Committee of the Disabled and Elderly was powerless and had done nothing to promote accessibility since it was formed. "The right to move freely in Houston usurps the recommendations of any committee," the ADAPT release said. A symbolic rally was held outside MTA's headquarters on Feb. l2 — Lincoln's birthday — to protest what ADAPT called a segregated transit system that makes slaves of the city's disabled population. Symbolism was also behind ADAPT's choice of Jan. l5, l986 Martin Luther King, ]r.'s, birthday — for its showdown with the Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART). Several of those same "outside agitators” who had irked the San Antonio Light made the 800-mile trip from Denver to participate in the demonstration. Among them was Mike Auberger, a quadriplegic community organizer for the Atlantis Community, who just may have been arrested more times than any other wheelchair activist in the movement. Auberger was not alone. Seventeen demonstrators, including several first-timers, were arrested. Denver's Kathy Vincent was among that group. Altogether the demonstrators managed to block l7 buses for more than six hours before the police stepped in and forcibly removed them from the streets. Not all the fireworks took place on the streets, however. The night before, at a regular monthly meeting of DART's executive board, ADAPT made known its intention to bring traffic to a standstill in Dallas the next day. "They laughed at us," Blank said. "They didn't think a handful of us could stop the buses." But Blank said DART's new executive director, Ted Tedesco, until recently a University of Colorado vice chancellor, knew different. “He knows what we can do. His face went white when we entered the room." At first, DART refused to hear from ADAPT. However, several ADAPT members began chanting "We will ride!", making it impossible for the DART meeting to continue. After making their presentation, several protestors showered the board with play money to symbolize the wasted tax dollars DART has put into non-accessible systems. Not all the news from Texas is bleak, however. ADAPT Austin has succeeded in winning 100 percent of off-peak hour accessibility from Capital Metro as of July 1, 1986. More than 50 percent of that city's peak hour routes will be accessible once l00 lift-equipped buses arrive this summer. Jim Parker reports that El Paso ADAPT is pushing the city to activate the 30 lift-quipped buses the system owns but has never operated. That would mean 50 percent accessible service during off-peak hours, according to Parker, who was among the first Texans to receive training from the Denver parent group. Auberger and other Coloradans had helped Parker block buses and stage a demonstration at a non-wheelchair-accessible McDonald's restaurant two years before.