- שפהAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

בית / אלבומים / תגיות Mike Auberger + Bob Kafka

+ Bob Kafka 31

31

ADAPT (745)

ADAPT (745)

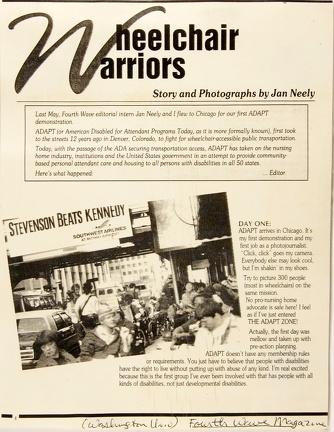

Fourth Wave Magazine (Washington University) [This article continues in ADAPT 729, 721 and 739, but it is included here in it's entirety for easier reading.] Wheelchair Warriors Story and Photographs by Jan Neely Editor's note: Last May, Fourth Wave editorial intern Jan Neely and I flew to Chicago for our first ADAPT demonstration. ADAPT (or American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today, as it is more formally known), first took to the streets 12 years ago in Denver, Colorado, to fight for wheelchairaccessible public transportation. Today, with the passage of the ADA securing transportation access, ADAPT has taken on the nursing home industry, institutions and the United States government in an attempt to provide community based personal attendant care and housing to all persons with disabilities in all 50 states. Here’s what happened: ..... Editor Photo: A city sidewalk jamed with wheelchairs and a couple of cameramen standing beside them between parked cars. Larry Biondi is on front right side of the photo. People are basically lined up waiting to move out. Article begins: DAY ONE: ADAPT arrives in Chicago. Its my first demonstration and my first job as a photojournalist. "Click, click" goes my camera. Everybody else may look cool. but I'm shakin' in my shoes. Try to picture 300 people (most in wheelchairs) on the same mission. No pro-nursing home advocate is safe here! I feel as if I've just entered THE ADAPT ZONE! Actually, the first day was mellow and taken up with pre-action planning. ADAPT doesn't have any membership rules or requirements. You just have to believe that people with disabilities have the right to live without putting up with abuse of any kind. I'm real excited because this is the first group I've ever been involved with that has people with all kinds of disabilities, not just developmental disabilities. DAY 2 Here's ADAPT (photo 1) blocking the doors of the auditorium in hope of catching Dr. Sullivan when he leaves. The Chicago police and the Secret Service put up barricades and pushed back the activists. Victoria Medgyesi, editor of Fourth Wave and my traveling buddy, used her press pass to get into where Dr. Sullivan was to ask him some questions. He refused to talk to her about Medicaid, ADAPT or nursing home abuse. PHOTO 1: A line of Chicago police officers face off against a line of ADAPT protesters in wheelchairs who come up to about the middle of the officer's chests. In the forground there is a barricade, but further back they are just right up against each other. PHOTO 2: Three men in wheelchairs (__________, ___________ and JT Templeton sit in an open area in front of a barricade. Behind the barricade is a crowd of people. JT holds a poster that reads "Sullivan where are you?" Article continues... DAY 2 cont. Usually ADAPT doesn’t go around the country crashing graduations, but this one was different (photo 2) Here we are at the University of Chicago where Dr. Louis Sullivan, Secretary of Human and Health Services, is speaking to students who are going to be medical professionals. For the past two years, ADAPT has been trying to talk to Dr. Sullivan about redirecting 25 percent of the Medicaid budget for personal attendant care into a home-based program. But he has refused to talk to ADAPT or to change the rules. As the graduation crowd went in, ADAPT passed out flyers. As l told one person, “What if you become disabled someday? What if your family couldn't take care of you?" As for the police, at this time they just stood back and watched. One of the reasons ADAPT has public demonstrations is to make the public aware of what's important to people with disabilities. Actions like this keep us going to meetings back home even though what we say is usually ignored. DAY 3 The next day we went to one of ADAPT's all time favorite places to "act up": the state office of Health and Human Services. It was only a few blocks away from our downtown hotel. so all 300 of us got in a single line and went for a little walk. Did I say little? Wait a minute. a line of 300 people in wheelchairs plus their supporters? Little? I will admit it was the most incredible thing I have ever seen. ADAPT does not stop when it goes on one of its “little walks." It does not stop for lights, trucks, cars, cops, or anything else. It also goes right down the middle of the street. But that's not to say ADAPT isn't nice, oh no! All along the way ADAPT gave the people of Chicago (who lined up on the curbs to watch as we wheeled and walked by) little gifts of knowledge: flyers with the real scoop on nursing homes. PHOTO 3: Amid a long line of ADAPT folks marching in their wheelchairs, a man (Mark Johnson) in a wheelchair talks with a man (Bill Henning) and a woman who are walking beside him. PHOTO 4: A city street lined by tall buildings, is filled by ADAPT protesters apparently crowded from one side to the other. Several people standing closest to the camera but facing away (Jimmi Schrode is on the far left) raise their hands, thumbs up. Article continues... DAY 3 cont. It was a thrill to watch ADAPT in action. When the whole group got to the Federal building, it was a big mess. We blocked off streets and almost shut the building down. As ADAPT told the police, the media and all the people who gathered; “We declare this building a Federal nursing home... only this time, no one goes in or out without our permission! " The reason many activists do this is because they once lived in nursing homes and other institutions and know how bad those places are. Boy, can I relate. I have mild cerebral palsy and I’m lucky to have always lived at home. But will I always be lucky? I feel that as long as there are institutions, they will be a threat to the kind of life my friends and I want to live. This laid-back looking guy is Mike Auberger. He is one of the original ADAPT activists. ADAPT may look like a bunch of disorganized hippies who lost the map to Woodstock 20 years ago, but the opposite is true. In Mike's backpack is one of ADAPT's three cellular phones and the base walkie-talkie! Bill Scarborough, an activist from Texas, keeps the computer nerds in the know by sending the word out from his laptop computer to computer bulletin boards across the country. ADAPT also has a media person who goes to whatever city ADAPT is demonstrating in several days ahead to let people know whats going to happen. PHOTO 5: A very intense looking man (Mike Auberger) in a power chair is sitting sideways to the camera. Behind him is some kind of vehicle and the ADAPT crowd filling the street. Tisha Auberger (Cunningham) is squatting on the bottom right of the picture. After nine long hours of blocking the building's doors, representatives from HHS finally agreed to meet in the street with ADAPT. It turned into a regular media pow-wow. Activists told the administrators and the media what was needed by people with disabilities. Photo 6: A gaggle of reporters and photographers tightly encircle the Regional HHS Director and several ADAPT protesters (Teresa Monroe, center, and Bob Kafka, right side). Article continues... We talked and they listened, but I have a feeling the concern I saw on those experts' faces was just the same old B.S. All of ADAPT's demonstrations are non-violent, but they are important battles in a war fought by people who are fighting to lead decent lives. The possibility of being arrested did make me nervous. It made me feel a little better when ADAPT told the new people that, if you got arrested, the group would never leave you alone. They said ADAPT would tell the cops your needs, get you a good lawyer, and stay on the outside of the jail chanting so you would know ADAPT was with you. Photo 7: Portrait shot of a man (Gene Rogers) with long brown hair and glasses, sitting in his wheelchair. He is wearing a T-shirt with a larger than life sized photo of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr's face and the words "VIOLENCE IS IMMORAL" and a lengthy quote below that is too small to read in the photo. Article continues... DAY 4 As l was getting dressed I thought to myself “Today ADAPT is taking on the AMA." Oh God. what have l gotten myself into? l mean the AMA! The Big Brother of the medical world; the people who are not only in charge of admissions to nursing homes, but who are also in charge of giving prescriptions to people like me. I thought: What if my doctor saw me and did not like what I was doing with ADAPT? Would he stop giving me my blood pressure pills that I can't afford to buy? What would happen then? What about the others? Aren't they in the same boat? I got a lot more out of my trip to Chicago than just a story and a few good pictures. I met some people who are important to the disability rights movement. I felt accepted and I came home with the feeling that together we can really change things. People with disabilities need to keep talking. We need to demonstrate. We need to tell the so-called "experts" the real truth and try not to be too afraid while were doing it. Insert text box: Incitement, Stephanie Thomas Editor. What's happening on the front lines? Read INCITEMENT, the official newsmagazine of ADAPT, and learn the who, what, when, where and why behind today's headline news. Free! To order contact: ADAPT/INCITEMENT 1339 Lamar SQ DR Suite B, Austin, TX 78704 (512)442-0252 Second text insert at end of article: Jan Neely is a photography student at Olympic Community College and an editorial intern at Fourth Wave. She is active in People First of Washington. the end ADAPT (744)

ADAPT (744)

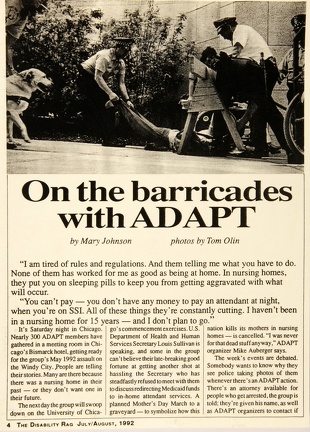

The Disability Rag July/August, 1992 [This article continues on ADAPT 738, 733,728, 724, 748, 743 and finally 737; however the entire text is included here for easier reading. ] Photo by Tom Olin: A policeman holds a wooden barricade while another tries to pull a protester who is lying on the ground by his pants legs backward and out from under the barricade. The protester is holding onto something above his head. On one side a third policeman seems to be coming over and on the other side a man (Frank Lozano) and his guide dog (Frazier) are coming over. Title: On the barricades With ADAPT by Mary Johnson photos by Tom Olin “I am tired of rules and regulations. And them telling me what you have to do. None of them has worked for me as good as being at home. In nursing homes, they put you on sleeping pills to keep you from getting aggravated with what will occur. “You can’t pay —— you don’t have any money to pay an attendant at night, when you’re on SSI. All of these things they’re constantly cutting. I haven’t been in a nursing home for 15 years — and I don’t plan to go.” It's Saturday night in Chicago. Nearly 300 ADAPT members have gathered in a meeting room in Chicago’s Bismarck hotel, getting ready for the group’s May 1992 assault on the Windy City. People are telling their stories. Many are there because there was a nursing home in their past — or they don’t want one in their future. The next day the group will swoop down on the University of Chicago's commencement exercises. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Louis Sullivan is speaking, and some in the group can't believe their late-breaking good fortune at getting another shot at hassling the Secretary who has steadfastly refused to meet with them to discuss redirecting Medicaid funds to in-home attendant services. A planned Mother's Day March to a graveyard — to symbolize how this nation kills its mothers in nursing homes — is cancelled. “I was never for that dead stuff anyway," ADAPT organizer Mike Auberger says. The week's events are debated. Somebody wants to know why they see police taking photos of them whenever there's an ADAPT action. There's an attorney available for people who get arrested, the group is told; they‘re given his name, as well as ADAPT organizers to contact if they get arrested. “I’m telling you — and it’s the most important thing I'm gonna say." Auberger warns the group. “have your medications with you if you're going to get arrested. Have ‘em labelled. No pill boxes; bottles. Make sure it has your name on it — nobody else's. Make sure there’s no illegal substances on you; no weapons. ‘Cos this is going to follow us down the road.” As it turned out, Chicago was mild compared to Orlando's confrontations last fall, in which nearly all ADAPT activists were thrown in jail — some in solitary confinement — for the week. In Chicago, only 10 people would be cited and fined in Monday’s confrontation at the HHS regional offices in downtown Chicago, and only 4 police-tagged “leaders” arrested the next day at American Medical Association headquarters; all were released at day’s end. Perhaps the national outrage in the wake of the Rodney King beating acquittal in Los Angeles a few weeks before had made Chicago police, considered to be some of the most brutal, cautious. The University of Chicago graduation turns out to be a beautiful Chicago spring day. Police and Secret Service are allowing ADAPT members into the auditorium without any hassle. Later, though, Jim Parker is asked to leave. He protests loudly as police haul him out a side door: “Why am l the only one being asked to leave?” About that time Tim Carver of Tennessee simply rolls off into the men's room, unnoticed, to wait out the sweep. Several ADAPT members unfurl a large FREE OUR PEOPLE banner over the wall below their seats, off in the “handicapped section" where the Secret Service have relegated them. Big burly Secret Service men with their walkie-talkies run over quickly and reach down to pull it up. Bob Kafka and Allen Haines are as determined that they won’t succeed. A kind of arm wrestling match ensues with Kafka and Haines holding firmly to the banner to keep it hanging over the wall where it forms a backdrop to the stage area where Sullivan will be speaking. The Secret Service have the advantage of leverage; they’re taller. One especially burly guy finally wrests the pole with its banner away from them and with a contemptuous jerk, flings it high into the bleachers behind them. “Clear ‘em out," mutters an all-business police captain. Four cops to a chair seems to be the agreed-on method of removal. Paulette Patterson of Chicago is removed this way. Over on the side, Anita Cameron and Jim Parker, back in and out of his wheelchair, and Frank Lozano, minus dog Frazier, are scooting down the steps on a side tier, trying to make it down to where Sullivan will speak, but they're caught and removed, too. “Get as close to the doors as possible,” says Bob Kafka to the other activists who have now been ejected from the back of the building. With police blocking doors. clots of ADAPT move to every entrance. Well, almost every one. Jean Stewart and Eleanor Smith use Stewart's crutches to pound on the metal doors, trying to create a disturbance inside, as the graduation ceremonies begin. Inside, though, the noise is barely audible. Nancy Moulton of Atlanta is sitting quietly on the ground, leaning on a door, with her guide dog Nan beside her. “Get up,” say a blue shirted Chicago cop. Moulton doesn‘t move. Nan rests her head on Moulton’s leg and rolls her eyes up at the cop towering over them. Now there are 4 Chicago cops and one guy who must be from the Secret Service hanging over Moulton and her dog. “If you don't move, we’ll have to grab you. and the dog will attack,” the cop persists. Still Moulton sits. “If you’re concerned about the dog, move!” the cop barks. Moulton gets up, worried that the cops will hurt Nan. While some block doors, others pass out leaflets to latecomers. The chants of “hey hey, ho. ho, nursing homes have got to go!" change to “We want Sullivan!" The police have barricaded the exit with blue sawhorses that read “police line." A pickup truck from the University's facilities management is unloading yellow university police barricades. A lady inside the back of the auditorium, hearing the faint chanting coming from outside, mutters, “they're not making friends." She‘s with the university. The University of Chicago is so large that commencement is held in two shifts; a morning one and an afternoon one. Sullivan has finished speaking and the crowd is emerging from the pavilion. They walk down the long fence of police barricades, while ADAPT chants and hands them leaflets: “Wanted: Sullivan. For crimes against disabled people." Inset picture: Beefy policeman with his cap down over his nose leaning forward. Caption: “If you care about your dog, move!” Article continues: It's lunch. ADAPT always feeds its activists. Today it‘s Burger King. Attendants and other walkies pass out cokes and burgers. Nan, Moulton’s dog, gets some much welcomed ice cubes from the big bag under the tree, put into the little folding plastic water bowl Moulton carries with her. A new crowd is coming to the arena. They, too, get leaflets and chants. Tim Craven has been ejected when police found him inside, but not before he and the other two who had hidden themselves in the press box get off a few good chants in Sullivan’s direction. A reporter for Habilitation, a disability magazine out of Seattle, has marched up to Sullivan, she reports, and asked him the questions ADAPT has so long wanted to ask him. To every single question, she says, he has responded, “It's a very nice day." Most of the students don‘t want to talk to a reporter. They have no comment. Some think that it‘s wrong of ADAPT to spoil their special day. Others think the group has a right to make itself heard — just not here, not now. One woman who has read the flyers says that "they don‘t want to be prisoners in nursing homes." A man, who hasn‘t read one, says he doesn’t know what they're protesting about but he thinks they have a right to do it. His daughter is graduating today —— with a degree in special education. Each ADAPT contingent blocking an entrance has its contingent of cops. The two `groups` joke with each other and pass the time in small talk. It's a lot like a chess game, says Haines; this trying to puzzle out where Sullivan‘s going to exit. Just about the time it occurs to several of the organizers who have been trying to psych out from which exit Sullivan will be spirited away that the one exit that has no guards on it is the parking lot entrance, a police car comes screaming down the street, makes an abrupt U-turn, and, at that moment, Sullivan's car, driven by Secret Service, shoots out of the entrance. Several ADAPT wheelers are on his tail in a flash, but it's too late. Sullivan again escapes— but the point, say the activists, has been well made to the over 10,000 people who have attended. Thousands of flyers have been passed out. PHOTO by Tom Olin: Inside a cavernous arena filled with people, two plain clothes police or Secret Service men have an ADAPT person (Bob Kafka) by the arms and are trying to lift him. He is sitting on the steps of an aisle leaning forward. To their right a young man in a button up shirt and jeans, a graduate, looks down at them. Caption reads: Getting to see Sullivan. Not. ADAPT makes no effort to block the streets surrounding the Pavilion. Monday‘s a different story. By 11am, both State and Adams Streets are blocked. Downtown Chicago is taking the flyers as fast as they’re being passed out. Many of them are surprisingly in agreement with ADAPT’s call for 25% of the current Medicaid money to be redirected to in-home services. One businessman engages Bob Kafka in a long and intense discussion over the merits of attendant services. He has buddies who were in Viemam, he says, and want the same thing Kafka does. He gives Kafka his card. Many other people are giving ADAPT members their cards, too; they are interested in the issue. Nobody, they say, has brought it up before. Certainly not the Chicago Tribune, which, instead of covering the baccalaureate brouhaha, runs a feature story on a college camp-out. “What I‘m looking for is a reasonable atmosphere to address the issues." Delilah Brummet Flaum, HHS’s Region V Director, would have to shout to make herself heard over downtown Chicago traffic and hundreds of milling demonstrators. And she‘s not shouting. She has come down, along with Chester Stroyny. Regional Director of the HealthCare Financing Administration and HCFA official David DuPre. in response to ADAPT demands. They want to meet with “officials”; they’ve blockaded the Region V HHS headquarters and aren‘t letting anyone in or out — unless they're willing to climb and crawl over protesters. About 20 activists have gotten all the way up to the HHS offices on the 15th floor, and have a bunch of police in there with them. It’s lunchtime by the time Flaum, Stroyny and DuPre are trotted out to Karen Tamley, Bob Kafka and Teresa Monroe and the others in the middle of Adams Street. ADAPT wants them to call Sullivan, to make him come back to Chicago and meet with them. Flaum can’t do that. “I am willing to do anything else you want us to do. to do try to get this resolved,” she’s saying. But she wants the group to be "more reasonable." She tells Tamley that she is “well aware" of ADAPT’s concerns, and that “the Bush Administration is working on non-institutional care options." Anna Stonum asks more questions. People in the crowd are starting to yell that they can’t hear. Flaum is telling Kafka that “shutting down a building“ is not the way to get a meeting with Sullivan. Kafka responds that they‘ve sent at least four letters to Sullivan and he's never responded to a single one. “You know as well as I do that the Secretary sets the tone for the discussion,“ Kafka lectures her. Kafka and DuPre engage in a debate about facts and figures. They can't trip Kafka up; he seems to know as much if not more about the issue than these folks do. At times the officials even seem to agree with him. Not, however, when he charges that “nothing the Secretary has said or done" changes anything “because he's in the pocket of the nursing home industry." “We disagree with that," say all three officials simultaneously. “We do favor the de-institutionalization model." “The damn Secretary has not said one thing — ever - has not even said the word ‘attendant services’ publicly," Kafka yells, and swears that ADAPT will continue to hold the building. “This is not being positive," says Flaum. “These are peoples' lives you’re talking about.” Kafka retorts. Photo Inset: The head of Bob Kafka, looking very intense, below the words "The damn Secretary has never even said the word 'attendant services' publicly." Article continues: “You don’t know what it’s like,” Monroe shouts at the officials when Kafka's done. “I want to talk to Sullivan. You get him here. He has no idea. Don't tell me Sullivan knows.” Monroe’s point, which she makes to Flaum, is that the money should go directly to the disabled person “because no person knows better what they need than the disabled person. Let us have our dignity.” She argues with Stroyny over nursing home inspections. Mark Johnson accuses Sullivan of “being in the pocket of the nursing homes.“ And meetings like this, he charges, aren’t worth a thing “unless there’s a commitment." The group, hearing Johnson, takes the cue: “We want a commitment!" One of the workers in the HHS office has come out for lunch and now finds she cannot get back in over the demonstrators. Still, she thinks what they're doing is “positive.” She’s a volunteer in a nursing home herself, she says, “And I know they’re the pits. People who don't frequent them don't know. These people who are walking around here” — she gestures to lunch-hour Chicagoans moving up and down the street-- “they could become victims of nursing homes, too. I look at these people here" —— and now she means ADAPT — “and I know I wouldn’t want to be jailed up in a nursing home." But then, she believes in protesting, she says. “I think protests are fine. I'm in tune with them. I was with Martin Luther King back in the 60s." she says. “I was in jail with Dr. King. I was 14 years old. That was just what you did; you went to jail. Some of our young people don't understand. “This is how to explain it,” she continues, warming to her subject. “These people want to get heard. We couldn’t get heard in Birmingham, either. That‘s why we marched on Washington." She won’t identify herself, though, but will only say she’s a spectator. But she works upstairs in the HHS office, she says. “And they got time to listen to that TV stuff — people come in talking about that, they make a big deal about the stuff they see on TV. And they got these people out here and they don‘t want to pay attention. When I was upstairs, they were callin’ ‘em ‘beasts’ and “vultures.” It is a measure of the erosion of belief in the system that has become the trademark of ADAPT that, when an EMS ambulance pulls up to the door and the word goes out that police are bringing down a man who’s had a heart attack, the thought passes among the group that this is yet another ploy. They think the stretcher rolled into the lobby and up on the elevator may be a ruse to make them move away from the door, which they nonetheless do, not wanting it to be said that they cared not for another disabled person who might be in danger. And when the man is brought down on the stretcher, there is more speculation: wasn’t he one of the officials out here earlier? Did the confrontation and excitement give him a heart attack? Is he faking? Is it really a medical emergency, or just :1 move to get someone out of the building who has an important meeting to attend and doesn't want it stopped by cripples? No one remembers the man in the stretcher more than a few minutes after the ambulance pulls away, lights rotating, into the Chicago traffic. Jane Garza from El Hogar del Nino is with the protesters. blocking a door by leaning against it. She’s part of the protest. she says: disabled herself, though she knows she doesn’t look it. She works in early childhood education. Some of the signs protesters are carrying were made by the children at her center, she says. “It's a way to bring them into it," she points out. The parents of the disabled kids at the center “are all reasonable people,” she says. “So they understand my being at an activity like this." If she gets arrested, she says, she has an understanding with her agency: they will bail her out. She’s been arrested with ADAPT before. she says; that was in Montreal. She’s been with ADAPT protests in Washington — the one to get the ADA passed; and one in St. Louis. “No one wants to see their child in a nursing home. People can really relate to that." She says the group at her door has been talking to passersby all day about the issue. “I was on the verge of going into a nursing home myself, back in ’82.” says this woman who doesn’t look disabled. When she had her aneurism and was in rehabilitation, she says, the Illinois Department of Rehabilitation Services gave her money with which she was able to pay two people — one for the morning, and one for the evening. “I just needed help getting up and then getting to bed. I was so weak. I just needed minimal assistance, somebody there to help me get dressed. But without that program. they would have put me in a nursing home.” Illinois Gov. Jim Edgar’s budget cuts have forced the Department of Rehabilitation Services to extend a freeze on intakes in that program through the end of 1993. and Edgar, Chicago ADAPT charges, is trying to eliminate a yearly cost-of-living adjustment for attendants. "After I got stronger, I was able to manage on my own. But look at how many people are in my shoes!” she says. “I worked; I had money. I was a social worker back then: one who had to apply for public aid just so I could get assistance." Insert picture: A person (possibly Lonnie Smith) with his head to one side and below the words “We want them to see what it’s like for us.” Article continues... The philosophy and tactic of doorblocking: Let people go in and out, if they’re willing to climb over you and your chair to do it. Arrest is not the objective here; inconveniencing people is. “We want them to see what it's like for us.” says one who has engaged in many door blockings. Photo by Tom Olin: A policeman stands in the middle of the street legs braced in a wide stance and arms streched out. He is holding a man with a cane (Gary Bosworth) with one hand and with the other hand and foot trying to hold back a man (Bob Kafka) in a manual wheelchair who is bent forward pushing. Other police officers are standing in the street, a supervisor is watching, as is a TV cameraman. Other protesters are partially visible at the edges of the scene. Chicago police have a black and white checkered band around their hats that is very distinctive. Article continues- Tuesday morning's Chicago Tribune, instead of covering ADAPT's HHS confrontation. reports on stepped-up security measures at the downtown State of Illinois building where. the Tribune reports, in error, ADAPT was "supposed" to be demonstrating Monday. ADAPT, it says, changed its mind. In fact, ADAPT planned to hit state offices on Wednesday. Speculation abounds as to who fed the paper the false information, the effect of which is to make ADAPT look disorganized. It later becomes apparent that state officials have had a hand in it. There is nothing in the Tribune about the people who stopped along State Street and asked questions, about Flaum, about any of it. The Sun-Times carries a photo inside. At the comer of State and Grant, a baby-blue police wrecker, the same blue as the cars, as the barricades, has blocked a curb ramp. ADAPT has blocked four intersections adjacent to the American Medical Association. Wheelchairs are stretched across 16 streets. At the intersection of Wabash and Grand, in the back, Paulette Patterson is hassling the policemen, mouthing off and chasing them with her motorized chair. It seems she is trying to get arrested. The police are being friendly enough. It won't be until noon that things will get rough. The cops will barricade the main entrances to the glass-walled fortress: many ADAPT members will take that as their cue to launch themselves out of their wheelchairs onto the high-curbed stoop around the building, crawling up to bang and hammer on the wooden barricades. A few find satisfaction in pounding on the glass walls. This will happen, though, only after the confrontation — the confrontation that resulted in Jerry Eubanks of Chicago being dropped from his wheelchair: picked up by his neck, it seems to other protesters, who holler for an “Ambulance! Now!”; the confrontation that causes Patterson to roll from her wheelchair and shriek at the top of her lungs, kicking her legs wildly as police try to pick her up. The police back off; when they come at her again, her screams again drive them back. Finally, Patterson is left alone, and, once more in her wheelchair, rolls off to the side, where she admits slyly and with her trademark smile that she enjoys discomfiting police. “They don't wanna mess with me," she says proudly. Suddenly they are all there again, surging at the entrance, trying to get up the high curb. Stephanie Thomas and Diane Coleman and others are wedging themselves in next to the Chicago Transit Authority paratransit vehicles that are a sure sign of arrests: it's the only way police can haul off a wheelchair to the hoosegow. Allen Leegant is diving under a barricade trying to get up to the entrance. Chris Hronis and Arthur Campbell are trying to follow; they are caught by police. Campbell is carried, spread-eagle, by four cops, directly to a CT A van. Cameras are everywhere; TV crews have materialized out of nowhere. Campbell has been arrested. Mike Auberger has been arrested. Campbell and Auberger are each put into his own van. The police have their eye on Mike Ervin. When you catch a snatch of cop-to-cop talk, you learn they're trying to pick off those they figure to be the leaders. “What the cops never understand is why the demonstration continues after they’ve hauled off the folks they think are leaders," says someone who is blocking a street. “They can’t figure out that arresting leaders doesn’t work; that as soon as they arrest someone, somebody else just moves in." Susan Nussbaum, blocking a side door, answers questions about whether the movement will ever see violence. “There’s always the potential for violence," she is saying. “But it would be good if that could be understood in the context of a larger issue. “I am not in favor of getting my head beaten in." At 3:15 the building starts to empty out. ADAPT has managed to block all the exits, so AMA workers and officials alike are subjected to a gauntlet of taunts as they trot, under tight police protection, down the ramp to the alley and across to the parking garage. The taunts seem mostly to be of the “AMA Shame On You” variety. When ADAPT members arrived at AMA headquarters in the morning, they found tables set up with water coolers and cups of refreshing water awaiting them. Later, the AMA‘s Department of Geriatric Health would confirm for a reporter that the AMA had done this so the disabled people wouldn't get overheated and get sick. Many protesters were wary of the water. Some suspected it had been spiked with Valium: others thought it a ploy to get them to have to pee later on, adding to their discomfort and hopefully ending the demonstration early. Much of the water was left untouched. Water was also running through hoses into the sprinkling system of the AMA‘s lawns. This had the added effect of keeping protesters off the grassy knolls fronting the building. Shortly after ADAPT arrived, one demonstrator had parked his chair on the hose while others moved across the area to block doors. Later, the water was simply turned off. Insert picture: A head and shoulders picture of a protester chanting, with the words "AMA: Shame on you!" "People are dying shame on you!" Article continues- The AMA’s flak, Arnold Collins, was standing around with the TV and radio reporters most of the day. The AMA had issued a statement insisting it “supports the home care objectives of ADAPT." Dr. Joanne Schwartzberg, Director of the AMA's Department of Geriatric Health, said in the news release that a meeting the previous Thursday with ADAPT had been “productive” and that the two `groups` had “considerable common ground.” Campbell, who attended the meeting, had a different analysis. He said he believed Schwartzberg truly had no understanding what ADAPT wanted; that some of their ideas had been totally inconceivable to her. Schwartzberg said ADAPT was the first group she had ever met with and felt “hostility.” “It was a great shock," she said. “I always thought of myself as being a great advocate. But I wasn’t an advocate enough for them." Schwartzberg said that ADAPT didn’t understand that there were “really frail people in nursing homes — a kind of frailty that these disabled don’t have. “I was really scared that the demonstrators might get harmed, the way they throw themselves out of their chairs.” she went on. “They’re very courageous; I think they're a little reckless. Luckily, nobody’s gotten seriously hurt." “Do you think she really believes the things she says, or do you think it’s just a pose?” a filmmaker wondered. The AMA had issued “a guideline for medical management of homecare patients," she said, and they were putting on 8 seminars for doctors “in managing home care.” She knew ADAPT wanted AMA members to divest themselves of their financial interest in nursing homes and cut nursing home admissions. But the AMA couldn‘t do that, she explained patiently. “We are a voluntary body. not a regulatory body." “They couldn't understand why we couldn‘t do more." she said. The Chicago Tribune was still concerned about the State of lllinois building. Every day Tribune stories had chronicled the increasing security at the site. On Tuesday, Paulette Patterson and another disabled woman filed suit in U.S. District Court alleging denial of access due to increased security. Though a temporary restraining order was not granted, Patterson’s attorney, Matthew Cohen, said filing the suit had had the desired effect. The Tribune covered the suit. Photos by Tom Olin: 1) Two protesters (Spitfire and Jimmi Schrode) in the march raise the power fist to woman leaning out of a second floor window yelling and giving them the thumbs up. Below on the sidewalk most people are just walking by but one older man looks on. Spitfire is wearing her combat helmet. 2) A line of ADAPT protesters face a set of barricades on the other side of which are a line of policemen holding the barricades with both hands. Midway down the line of protesters, a man in a wheelchair (Danny Saenz) is turned toward the camera and another protester (Chris Hronis). 3) Close up of a man in a wheelchair (Rene Luna) who sits in front of an almost life sized portrait of IL Governor Edgar. Rene is holding a poster that reads "nursing home industry owns Edgar." Article continues- Finally, on Wednesday, ADAPT obliged the Tribune and state officials by staging a protest at the building, drawing attention to stale policies that were cutting people off from attendant services in Illinois. On Thursday. the Tribune ran a long story on ADAPT. Calling them "a group of vociferous activists savvy in street action." It quoted a miffed Chicago official who refused to be named saying that "one of the strongest points in their civil disobedience is making themselves look as pathetic as possible.“ “The group's history is rife with attention-grabbing acts of protest." said the Tribune. which compared them to ACT-UP and Earth First! protest `groups`. "Though some may question their tactics. none can doubt they have impact.“ said the Tribune. the end US_Capitol_Rotunda_part_2_cap

US_Capitol_Rotunda_part_2_cap

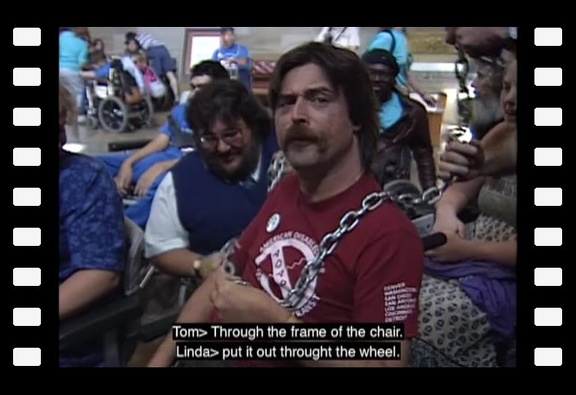

This is part 2 of the ADAPT Capitol Rotunda protest in support of the Americans with Disabilities Act, ADA. This shows the group preparing for civil disobedience to pressure swift passage of the bill. Over 100 people were arrested at this protest, which gets less attention than the Crawl but was equally intense. The film is open captioned (as are all videos on this museum site).![ADAPT (801) (2181 visits) The Washington Post, Metro Section 5/6/93

[Headline] The Disabled Plan to Show Washington They'r... ADAPT (801)](_data/i/upload/2019/09/12/20190912141402-36d6c423-sm.jpg) ADAPT (801)

ADAPT (801)

The Washington Post, Metro Section 5/6/93 [Headline] The Disabled Plan to Show Washington They're Enabled—and Entitled By Liz Spayd, Washington Post Staff Writer Michael Auberger has shackled his wheelchair to city buses in Dallas. He has barricaded hotel entrances in San Francisco, and he has thrown himself in front of federal buildings, government officials, even oncoming traffic, all to draw attention to the rights of the disabled. This weekend, Auberger and hundreds of other activists from across the country plan to converge on Washington for a three-day blitz of demonstrations and marches in what promises to be the largest protest in history for people with disabilities. “We've written the letters, made the phone calls, had the meetings, and the bottom line is we're still being treated like second-class citizens." said Auberger, co-founder of ADAPT, an activist group that is spearheading the activities. “lf those channels don't work, you take to the streets." Organizers say the immediate purpose of the demonstrations is to demand that the federal government commit more money to helping disabled people live at home, instead of in institutions. At the same time, they want to continue the larger campaign for equal rights that produced the Americans With Disabilities Act, landmark legislation that went into effect last year. A march to the White House and a memorial service for Wade Blank, who was a leader in the movement, are expected to draw the largest crowds, both on Sunday. What may draw the most attention, however, are demonstrations on Monday and Tuesday, when protesters are expected to disrupt Washington with human blockades of buildings and streets. The exact places and times for those actions aren't being disclosed, but the targets could include public buildings, such as the Capitol and the White House, and some federal agencies. “We like to preserve the element of surprise," Auberger said. ADAPT — an acronym for American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today — has been staging protests every six months for more than a decade to fight what it says is the inhumane treatment of the disabled at nursing homes and other institutions. The group said it hopes to redirect 25 percent of the $23 billion in Medicaid funds currently budgeted for nursing homes into programs that would enable those with disabilities to have attendants in their homes. Currently, each state sets policy for how much Medicaid money will go toward attendant care programs, but there is no national policy. [Subheading] Disabled Activists Plan 3-Day Protest The strike on Washington is timed to pressure the Clinton administration into focusing on people with disabilities as part of its package of health care revisions, due out soon, activists said. "Clinton has talked about change and says he wants people to be able to live at home, but what we're looking for is more than just words," said Bob Kafka, an ADAPT organizer in Texas who plans to bring a caravan of about 50 people to Washington. In the past, ADAPT activists have drawn attention to their cause by employing sometimes sensational tactics. They have done belly crawls across hotel lobbies in San Francisco, clawing at passersby. They have taken sledgehammers to street curbs in Denver to protest sidewalks that were inaccessible to wheelchair users. And they have swarmed and blockaded buildings in virtually every major U.S. city; a demonstration in Chicago last spring forced the evacuation of more than 1,000 American Medical Association workers and created disruptions in a half-dozen other downtown facilities. Though such events have attracted media attention, some individuals and `groups` sympathetic to ADAPT’s cause question how effective they are in achieving the larger goal of attaining more money for in-home care. “We're sympathetic to their concerns, but we think the tactics they use bring attention to ADAPT and not the problem," said Claudia Askew, a spokeswoman for the American Health Care Association, which represents 11,000 nursing homes and is a frequent target of ADAPT protests. Disabled people also are somewhat splintered over whether ADAPT's approach helps or hurts their cause. “There are people with disabilities that think ADAPT is a little extreme," said Patrick McCurdy, vice president of Marylanders for Adequate Attendant Care, a group that generally relies on peaceful protests and negotiations to lobby for in-home care. McCurdy did defend ADAPT's technique as a necessary part of an overall approach to force change in a society that he said has long ignored the rights of disabled people. Few spoke up for those rights until recently, but the Americans With Disabilities Act provided new protections to disabled people and helped forge a civil rights movement among the 43 million people with physical or mental impairments. “A great byproduct of the [disabilities act] is the new sense of confidence and empowerment it has instilled within the disability community," said Justin Dart, chairman of the President's Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities, a small federal agency. “It's generated an enormous infusion of dignity and pride." Gregory Dougan, a District resident, said the renewed sense of hope is one reason he will take part in Sunday's march. Dougan, who was born with cerebral palsy and uses crutches, said he is fortunate to be able to live at home. But several of his friends live in institutions because they can't get the in-home care they need. And on Sunday, Dougan said, he will be thinking of them. "I'll be tired at the end of the day," he said, "but my crutches and me are going to that march." ADAPT (768)

ADAPT (768)

San Francisco Examiner TITLE: Disabled protest for more funds for home attendants Subheading: Entrances to downtown Marriott are blocked By Wylie Wong of the Examiner Staff, October 19, 1992 About 300 demonstrators in wheelchairs blocked the entrances to the San Francisco Marriott, calling for more funds to allow the disabled to live outside of nursing homes. Sunday's protest was designed to drew attention to the 16 million disabled people who have no choice but to live in nursing homes, said the Rev. Wade Blank, a co-founder Americans Disabled for Attendant Programs Today (ADAPT). The protesters targeted the American Health Care Association, a nursing-home trade group whose members are staying at the Marriott on Fourth and Minion streets while attending a convention at nearby Moscone Center. ADAPT wants 25 percent of the $27 billion paid to nursing home operators under the Medicaid program to be used to help disabled people pay for personal attendants. But the Bush administration and the health care association, which represents about 10,000 nursing homes, oppose the plan. Only $600 million of that money currently is used for in-home attendant care, said ADAPT co-founder Michael Auberger. Police escorted the protesters on the eight-block trip from their Market Street hotel, and watched as they barricaded themselves at the Marriott's entrances. The protesters chanted. "Down with nursing homes, up with attendant care.” Police were able to keep some entrances open for hotel guests. No arrests were made. Kimberly Horton, who lived in a nursing home from age 6 to 21, described her experience as “living in a prison." "They take away your personal dignity," she said. "You had to eat what they put in front of you. They'd get angry at me for wetting my bed, but wouldn't help when I had to go.” Protester Blane Beckwith, a Berkeley resident, has a personal attendant who takes care of his everyday needs, from taking a bath to preparing food. But state budget cuts have slashed eight hours of care per month. As a result, he has only half an hour per week for grocery shopping with his attendant. "No one can shop for groceries in half an hour, My mother helps me, but she's 62 and can't do it forever." he said. Horton, who wants to take writing classes and become a free-lance writer, fear that more budget cutsar will force him to live in a nursing home. "A nursing home is stifling," he said, "You have no social life. You can't work." Conventioneers who walked past the protesters were unimpressed. "I have no argument with wanting more attendant care,” said John Jarrett, who runs a 79-bed nursing home in New York. "But they shouldn't take it from the elderly,” who would be hurt if ADAPT funding plan were implemented, he said. The demonstrators plan to protest the convention through Friday. A police commander said 90 police officers were on hand. “They haven’t been violent,” he said. “They’ve been very cooperative.“ Last week, officers took two hour classes at the Police Academy to learn how to arrest and search disabled people without harming them. PHOTO by Michael Macor, Examiner: The front of the ADAPT group marching down a downtown street and in the background the line of marchers goes out of sight. Paulette Patterson, Julie Nolan, Carla Laws, Brooke Boston? and Bob Kafka among those leading the march. Photo caption: Disabled people from the group ADAPT make their way down Mission Street to the Marriott Hotel. Rotunda part 1

Rotunda part 1

This is part 1 of the story of the ADAPT protest in the Capitol Rotunda to call for passage of the ADA with no weakening amendments. The ADA had become bogged down in the House and there was concern the bill would not pass. The day after the Wheels of Justice March and the Capitol Crawl, ADAPT took over the Rotunda of the United States Capitol building and over 100 people were arrested protesting for our civil rights. This is almost raw footage and gives a real sense of the event as it unfolded. Part 2 of this action is included in the next video Capitol Rotunda part 2. ADAPT (666)

ADAPT (666)

Looking into a crowd of ADAPT folks. Bob Kafka in center is talking through a microphone. Left of him is Chris Colsey with a headband, to Bob's right is Mike Auberger looking down, Bobby Thompson facing sideways, and Jane Embry. Directly behind Bob is Robert Reuter facing backwards, and another man from Chicago or Atlanta ? In the row behind them (L-R) Jimmy Small, Wayne Becker, Marilyn of Atlanta, Bernard Baker, and behind them other ADAPT members. In front on left Shel Trapp is facing the group at edge of picture, and Mike Ervin is facing forward. ADAPT (395)

ADAPT (395)

St. Louis Post Dispatch 5-22-88 PHOTO by Ted Dargan/Post Dispatch: A Line of ADAPT people roll down a city street. The first person in line (Mike Auberger) has two long braids and sunglasses. His arms hang on either side of his motorized wheelchair and his ADAPT shirt is somewhat covered by the chest strap on his chair. Next to Mike is a man in a manual wheelchair with curly hair and a beard (Bob Kafka) who has is legs crossed and is wearing the same ADAPT shirt as Mike. Behind them a man (Jerry Eubanks) with no legs in a manual wheelchair is being pushed by a blind man (Frank Lozano) who is smiling. Behind them is another man in a maual wheelchair. Behind him is someone in a motorized wheelchair who is looking off to the side. Behind them is another person in a wheelchair. The photo is grainy so it's hard to make out many details. Caption reads: Disabled people demonstrating downtown last week for more accessible bus service. Title: Bus Stop By Joan Bray Of the Post-Dispatch Staff ACTIV1STS FROM local advocacy groups were absent from the scores of protesters who took to St. Louis streets last week asserting the rights of the disabled to accessible bus service. Leaders of the local groups say tactics, not goals, caused them and their members to opt out of the demonstrations. About 150 people blocked entrances at Union Station and surrounded buses at the Greyhound terminal. A majority of them were in wheelchairs, on crutches or otherwise disabled. And they were out-of-towners. They belong to a loosely woven group, American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, called ADAPT for short. The group was protesting the policies of the American Public Transit Association, which was holding a regional meeting at the Omni International Hotel at Union Station. As a result of ADAPT's civil disobedience, 78 arrests were made, two group court appearances were held and a lawsuit was filed by the group over treatment at the City Workhouse. We support ADAPT's policies on access 1,000 percent," said Max J. Starkloff. He is executive director here of Paraquad Inc., which advocates rights for the handicapped. "But we have not participated in the demonstrations." "Our methods are negotiation, public testimony and organized public rallies," Starkloff said. "Our goals ore the same" as ADAPT's. Both the local activists and ADAPT want the transit association to push for installing a wheelchair lift on every bus in the country. They see 100 percent accessibility as a civil right. Rut the transit association notes in a written statement that no such accessibility is required by the Constitution, the Congress or the courts. It says the number of lifts on buses has increased to 30 percent now from 11 percent in 1981. In that same period, the administration of President Ronald Reagan has slashed the federal transit program's budget by 47 percent, the association says. The association says each local transportation agency should be allowed to determine how it will provide access for the disabled. Special services — like the Call-A-Ride service operated by the Bi-State Development Agency — may work better than lift-equipped buses in some areas, the association says. Local groups' methods for effecting change include working within the system. Starkloff serves on Bi-State's committee on transit for the elderly and disabled. The chairman of that committee, Fred Cowell, is executive director of the Gateway chapter of Paralyzed Veterans of America. Bi-State has made a commitment to install wheelchair lifts on all its buses, Cowell said. But the committee wants the agency's board of directors to adopt a policy stating it will do so. "We know that the buses are here to stay," Cowell said. "If or when budget cuts come, special services such as Call-A-Ride would be the first to go." Cowell and Starkloff said they feared that between the bureaucracy and the protests, the primary point — the need for equal transportation — was being missed. "A disabled person is not unlike any other person," Cowell said. Disabled people need to get to their jobs, to medical care and to social engagements, be said. "There is absolutely no difference in their need to get around," he said. Starkloff noted that the cost of a van equipped for a wheelchair — a minimum of about $20,000 — was prohibitive for most people. But the disabled should not have to wait at a bus stop on the chance that the next bus may be equipped with a lift, be said. Nor should they have to plan their trips 24 hours in advance, as Call-A-Ride requires, he said. Cowell said, "The main thing the (BI-State) committee has been trying to do is develop a deepening concern for services for the disabled and elderly." The fact that the committee has been successful in persuading Bi-State to buy only buses with lifts prevented the agency from bearing the brunt of ADAPT's effort here, one of the protest leaders said. The Rev. Wade Blank, a Presbyterian minister from Denver, is a co-director of ADAPT. He has a daughter who is disabled. Two months ago, representatives of ADAPT met with State officials in preparation for their trip here and learned of the agency's commitment to lifts, Blank said. As a result, ADAPT aimed its protests at the transit association's meeting and Greyhound Bus Lines. Greyhound is bidding on local routes in some metropolitan areas — Dallas, for one, Blank said. But it does not equip its buses with lifts, he said. A spokesman for Greyhound said last week that, instead, it provided a free ticket for a companion for a disabled traveler. Regarding the transit meeting, Blank said: "Our whole intent is to go after people who are so much wrapped up in the system that they insulate themselves from the issue. They have to live and breathe (ADAPT's protests) when they go to these conventions." Demonstrators here represented some of ADAPTs 33 chapters across the country, Blank said. He said his headquarters was with a group in Denver called the Atlantis Community, which moves disabled people out of nursing homes into independent living arrangements. Funding comes primarily from church donations and foundation grants, he said. From 1978 to 1981, ADAPT protested — and "caused a major disruption" — in Denver every month, Blank said. In 1982, the buses there became 100 percent equipped with lifts, he noted. ADAPT has since protested in all the cities where the transit association has met and where it has been invited by other activists, for a total of about 15 cities, Blank said. [unreadable] ...only buses with lifts, he said. Blank said the failure of local groups to join ADAPT's protests did not weaken the cause. Another success that ADAPT points to is a ruling by a federal Judge in Philadelphia in January striking down a regulation of the US. Department of Transportation that allows transit authorities to spend only 3 percent of their budgets on the disabled. The Judge postponed the effect of the ruling while the Justice Department appeals it. Three percent of Bi-State's budget for the current fiscal year Is $2.6 million, said Rosemary Covington, an agency official who works with the advisory committee. But Bi-State will spend only $1 million because of delays in getting bids on new buses and in expanding the Call-A-Ride service. "We are having budget problems, but that wasn't the reason" the money wasn't spent, Covington said. The remaining $1.6 million does not roll over to the fiscal year that begins July 1, she said. She said that by early next year, Bi-State expected that 221 of its fleet of about 700 buses will be equipped with lifts, 12 of the more than 120 routes will be operated entirely with lift-equipped buses, the Call-A-Ride service will include all of St. Louis County and the city and a voucher system will be available for back-up cab service. Equipping all the agency's buses with lifts will take six to seven years, Covington said. Meanwhile the committee will help evaluate the services for the disabled, she said. "If ridership doesn't materialize" on the buses with lifts or "if it costs thousands or millions (of dollars) to maintain them, that will enter into the decision making," Covington said. Bi-State is training drivers how to use the lifts and plans to promote and advertise the service heavily, she said. ADAPT (386)

ADAPT (386)

Montreal Daily News Title: A wheelchair Army Goes to War! [This article continues in ADAPT 385 but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] Photo 1 by ALLAN R LEISHMAN/Montreal Daily News: In a crowd of uniformed police officers and others, two policemen stand on either side of a protester sitting on the wet ground. The protester sits, back to the camera, wearing a cap and his face and head are obscured by a white trash bag under his jacket. These two police officers are looking back beside the camera. The police barricade is just visible in front of the protester. Caption: Roundup: Police are kept busy by demonstrators last night. Photo 2 on the left and below the other photo by ALLAN R LEISHMAN/Daily News: A person in a manual wheelchair is tipped completely back by attendant and protester Jan Ingram the front wheels of the chair are hooked over a very low heavy metal barrier. Behind that barrier are standard police barricades and uniformed officers are standing behind them. One policeman is in between the standard barricades and the low barrier and he is looking at other officers and pointing at the person in the wheelchair. Caption: Protesting: One of the wheelchair demonstrators near the barricaded Queen Elizabeth Hotel. Title: 25 arrested in downtown demonstration by Ron Charles Montreal Daily News MUC police arrested 25 wheelchair-bound demonstrators last night after they forced their way into the lobby of the Sheraton Centre in downtown Montreal. The demonstrators were protesting the American Public Transit Association's (APTA) reluctance to endorse wheelchair lifts on new buses. They crashed their wheelchairs through a luggage-cart barrier hotel employees had built in an attempt to ward off the protesters. [Subheading] Came along When APTA, a Washington-based transit authority organization, brought its annual conference to Montreal this week, the protesters came along as part of the ticket. The demonstrators, from a group called American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT), have been protesting at APTA conferences for eight years. Only a few members of a local disabled rights group took part in the demonstrations — the rest were from the U.S. Police said all those arrested — who are expected to be charged with assault — were American citizens, many of them Vietnam veterans. About 50 MUC police officers showed up to clear the Sheraton's marble-covered lobby after the protesters, singing "we want to ride," blocked elevators and escalators. Police wheeled the demonstrators one by one to a waiting wheel-chair bus being used as a paddy wagon. Police snipped chains linking protesters Mike Auberger and Bob Kafka's wheelchairs to a handrail in the lobby. Although the APTA conference is taking place at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, some of the 3,000 attendees are staying at the Sheraton. Earlier in the day, police turned the Queen Elizabeth into a fortress with metal street barriers as about 75 demonstrators wheeled toward the APTA conference headquarters. They blocked traffic in both directions on Dorchester for more than two hours as police tried to pen the group in with the barriers. Police took two protesters who had crashed the barriers out of their chairs in order to lift them and their chairs over the barriers. [Subheading] Took chair "The police took his chair away, separated him from his legs," said Lori Taylor as she watched from the side-walk when police lifted her husband, Lester, over the barrier. "He can't walk, he's just sitting on the wet ground and all he wants to do is ride a bus like you and me." Bill Bolte, who started ADAPT's Los Angeles chapter, said police overreacted to the demonstration. "This really confuses me because I know that after the Canadians (hockey team) won the Stanley Cup, all types of terrible activity went on," said Bolte. "People overturned cars while everyone, including the police, just looked the other way and went and had a cup of coffee." Several demonstrators who broke through the police perimeter smashed their chairs into barriers in front of the hotel entrance, but hotel security and police stood their ground. Police arrested some 25 wheelchair demonstrators after they forced their way into the lobby of the Sheraton Centre. They were protesting the American public transit association’s reluctance to endorse wheelchair lifts on new buses. It was showdown time yesterday, as wheelchair-bound protesters took on city cops outside the Sheraton hotel on Dorchester Boulevard Some demonstrators where roughly carried and wheeled away as the melee grew ugly. The protesters were making their case for better accessibility to buses at the American Public Transit Association convention. ADAPT (403)

ADAPT (403)

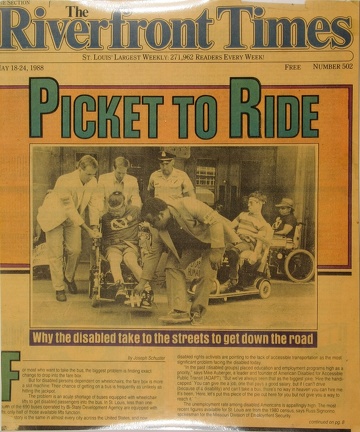

The Riverfront Times, ST. LOUIS' LARGEST WEEKLY: 211,962 READERS EVERY WEEK! MAY 18-24, 1988 [This article continues in ADAPT 398, but the entire text is included here for easier reading] PHOTO: Three plain clothes policemen try to hold back a man in a motorized wheelchair (Ken Heard). One is behind Ken, one beside him holding the armrest and the third is in front bending forward trying to manipulate the driving mechanism that is on the footrest of Ken's wheelchair. (Ken drove his chair with his foot.) Ken is in shorts and an ADAPT shirt and wears a pony tail and head band, and he is leaning forward concentrating on trying to control his chair. A uniformed policeman looks on from behind or is possibly looking to help. On the right side of the photo, another man in a scooter (Tommy Malone from KY) is watching. Behind him is a set of glass doors and blocking one is a woman in a wheelchair (Barbara Guthrie of Colorado Springs). She is wearing dark glasses and a brimmed hat as well as her ADAPT shirt. title: Picket To Ride, Why the disabled take to the streets to get down the road by Joseph Schuster For most who want to take the bus, the biggest problem is finding exact change to drop into the fare box. But for disabled persons dependent on wheelchairs, the fare box is more a slot machine: Their chance of getting on a bus is frequently as unlikely as hitting the jackpot. The problem is an acute shortage of buses equipped with wheelchair lifts to get disabled passengers into the bus. In St. Louis, less than one-fourth of the 690 buses operated by Bi-State Development Agency are equipped with lifts; only half of those available lifts function. The story is the same in almost every city across the United States, and now disabled rights activists are pointing to the lack of accessible transportation as the most significant problem facing the disabled today. "In the past (disabled groups) placed education and employment programs high as a priority," says Mike Auberger, a leader and founder of American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT). "But we've always seen that as the biggest joke: 'Hire the handicapped.' You can give me a job, one that pays a good salary, but if I can't drive (because of a disability) and can't take a bus, there's no way in heaven you can hire me. It's been, 'Here, let's put this piece of the pie out here for you but not give you a way to reach it. The unemployment rate among disabled Americans is appallingly high. The most recent figures available for St. Louis are from the 1980 census, says Russ Signorino spokesman for the Missouri Division of Employment Security. [at this point in the article the first column is cut off on the left, slightly] According to that census, there were 119.000 [disa]bled St. Louisans. but only 48,000 were in [the] work force. says Signorino. Of the 71,000 of the labor force. 59.000 did not work [bec]ause their disability prevented them from [emp]loyment. The balance of 12,000 disabled [unclear]ons were so-called "discouraged workers." [Indi]viduals who had stopped looking for work [beca]use of various factors. ‘You're going to find a higher percentage of [disc]ouraged workers among the disabled (than [amo]ng the general population)." Signorino [said]. Nationally, less than one-third of the country's 13 million disabled are in the labor force, according to the Statistical Abstract of the United States 1986, the most recent edition to {unclear] information on the employment status of disabled Americans. Of those who are in the work force, almost {unclear]-fifth are unemployed. ("Discouraged" workers are not included in the work force; those who are unemployed. but looking for work. are.) This is compared, in the same year, with the able-bodied population of the country, which nearly 70 percent of 133 million persons were in the workforce and 9.6 percent of those were unemployed. The problem of lack of access to public transit brought Auberger and more than 100 other members of ADAPT to St. Louis this week to demonstrate at the annual meeting of Eastern region of the American Public Transit Authority [sic] (APTA), the industry's [principal] trade organization. ADAPT wants the transit industry to move toward what ADAPT calls "100 percent accessibility." That is every bus in the country would have wheelchair lifts. But APTA opposes that saying it is impractical and too expensive. It favors, instead, what is known as "local option." Each transit authority would decide how it would make public transportation accessible for the disabled, using either buses equipped with lifts, paratransit vans with lifts (the so-called dial-a-ride services, or a combination of the two. Right now, 18 percent of the nation's systems use lift-equipped buses exclusively, 44 percent use paratransit vans and the remainder — including St. Louis — use a combination. Nationally, according to APTA Deputy Executive Director Albert Engelken, one in three buses is lift-equipped. That is progress, Engelken says. In 1980, only about 11 percent of the nation's buses were lift-equipped. But for ADAPT and others in the disabled community, the progress is too slow. “I'm damned impatient," says Jim Tuscher, vice-president of programs for Paraquad, a St. Louis non-profit agency that serves disabled people. "I personally have been involved with Bi-State for well over 10 years, negotiating, trying to get an accessible transit system and today we still do not have an adequate system. Sure, their attitude is better now than it was 10 years ago, in that they are willing to cooperate with the disabled community. They had to be dragged, kicking and screaming into this. But I‘m a results person and so far I haven't seen any. I still can't go out to the corner and take a bus." Currently, 171 (24.8 percent) of Bi-State's 690 buses are equipped with wheelchair lifts. Tom Sturgess, the company's director of communication, says the system has a goal of 100 percent wheelchair accessibility, but getting there is a slow process. Later this summer, the number of lift-equipped buses will be increased to 238, but that will still mean that only one in three Bi-State buses can be used by a disabled person. Sturgess says Bi-State has notified its manufacturer that it will be buying another 60 lift-equipped buses sometime in the near future. Of the company's present 171 wheelchair lifts, only 85 (or just less than half) function. “We've had a lot of problems with them." says Sturgess. “The new buses we're getting will have a different kind of lift in them, one we think will work. Of those we have, we're in the process of repairing as many as we can, but some will never operate again. We're convinced it wouldn't be economically feasible to do so. The biggest problem is the salt they spread on the streets and highways. It sprays up into the lift mechanism, corrodes the wires and rusts the lifts.“ Because there are so few lift-equipped buses at present, only 16 to 18 of Bi-State's 129 routes have accessible buses, says Todd Plesko, Bi-State's director of service planning and scheduling. But not every bus that travels those routes has a lift. For example, on Bi ADAPT (267)

ADAPT (267)

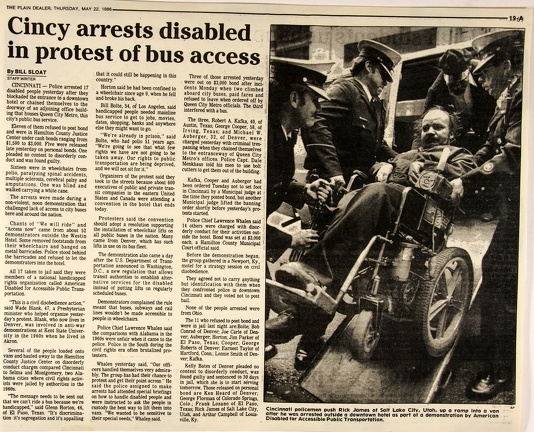

THE PLAIN DEALER, THURSDAY, MAY 22; 1986 page 19-A PHOTO by AP: Four policemen in their fancy police hats are "rolling" a man (Rick James) up a 150 degree (ie. almost vertical) "ramp" into a van. Rick is sitting with his hands up by his chest. His hat is missing and his hair is flying out in all directions. His expression is a mix of amazement, disgust and resignation. Caption reads: Cincinnati policemen push Rick James of Salt Lake City, Utah, up a ramp into a van after he was arrested outside a downtown hotel as part of a demonstration by American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation. Title: Cincy arrests disabled in protest of bus access By BILL SLOAT STAFF writer CINCINNATI — Police arrested l7 disabled people yesterday after they blockaded the entrance to a downtown hotel or chained themselves to the doorway of an adjoining office building that houses Queen City Metro, this city’s public bus service. Eleven of them refused to post bond and were in Hamilton County Justice Center under cash bonds ranging from $1,500 to $3,000. Five were released late yesterday on personal bonds. One pleaded no contest to disorderly conduct and was found guilty. Sixteen were in wheelchairs from polio, paralyzing spinal accidents, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy and amputations. One was blind and walked carrying a white cane. The arrests were made during a non-violent, noon demonstration that challenged lack of access to city buses here and around the nation. Chants of “We will ride" and “Access now” came from about 52 demonstrators outside the Westin Hotel. Some removed footstands from their wheelchairs and banged on metal barricades. Police stood behind the barricades and refused to let the demonstrators into the hotel. All 17 taken to jail said they were members of a national handicapped rights organization called American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation. “This is a civil disobedience action," said Wade Blank, 47, a Presbyterian minister who helped organize yesterday's protest. Blank, who now lives in Denver, was involved in anti-war demonstrations at Kent State University in the 1960s when he lived in Akron. Several of the people loaded onto vans and hauled away to the Hamilton County Justice Center on disorderly conduct charges compared Cincinnati to Selma and Montgomery, two Alabama cities where civil rights activists were jailed by authorities in the 1960s. “The message needs to be sent out that we can’t ride a bus because we're handicapped,” said Glenn Horton, 46, of El Paso, Texas. "It's discrimination it’s segregation and it’s appalling that it could still be happening in this country." Horton said he had been confined to a wheelchair since age 9, when he fell and broke his back. Bill Bolte, 54, of Los Angeles, said handicapped people needed mainline bus service to get to jobs, movies, dates, shopping, banks and anywhere else they might want to go. “We're already in prison," said Bolte, who had polio 51 years ago. “We're going to see that what few rights we have are not going to be taken away. Our rights to public transportation are being deprived, and we will not sit for it." Organizers of the protest said they took to the streets because about 600 executives of public and private transit companies in the eastern United States and Canada were attending a convention in the hotel that ends today. Protesters said the convention should adopt a resolution supporting the installation of wheelchair lifts on all public buses in the nation. Many came from Denver, which has such lifts in use on its bus fleet. The demonstration also came a day after the U.S. Department of Transportation announced in Washington, D.C., a new regulation that allows transit authorities to establish alternative services for the disabled instead of putting lifts on regularly scheduled buses. Demonstrators complained the rule meant that buses, subways and rail lines wouldn't be made accessible to people in wheelchairs. Police Chief Lawrence Whalen said the comparisons with Alabama in the 1960s were unfair when it came to the police. Police in the South during the civil rights era often brutalized protesters. Whalen yesterday said, “Our officers handled themselves very admirably. The group has had their chance to protest and get their point across." He said the police assigned to make arrests had attended special briefings on how to handle disabled people and were instructed to ask the people in custody the best way to lift them into vans. “We wanted to be sensitive to their special needs." Whalen said. Three of those arrested yesterday were out on $3,000 bond after incidents Monday when two climbed aboard city buses, paid fares and refused to leave when ordered off by Queen City Metro officials. The third interfered with a bus. The three, Robert A. Kafka, 40, of Austin, Texas; George Cooper, 58, of Irving, Texas; and Michael W. Auberger, 32, of Denver, were charged yesterday with Criminal trespassing when they chained themselves to the entranceway of Queen City Metro's offices. Police Capt. Dale Menkhaus told his men to use bolt cutters to get them out of the building. Kafka, Cooper and Auberger had been ordered Tuesday not to set foot in Cincinnati by a Municipal judge at the time they posted bond, but another Municipal judge lifted the banning order shortly before yesterday's protests started. Police Chief Lawrence Whalen said 14 others were charged with disorderly conduct for their activities outside the hotel. Bond was set at $3,000 each, a Hamilton County Municipal Court official said. Before the demonstration began, the group gathered in a Newport, Ky., motel for a strategy session on civil disobedience. They agreed not to carry anything but identification with them when they confronted police in downtown Cincinnati and they voted not to post bail. None of the people arrested were from Ohio. The 11 who refused to post bond and were in jail last night are: Bolte; Bob Conrad of Denver; Joe Carle of Denver; Auberger; Horton; Jim Parker of El Paso, Texas; Cooper; George Roberts of Denver; Earnest Taylor of Hartford, Conn.; Lonnie Smith of Denver; Kafka. Kelly Bates of Denver pleaded no contest to disorderly conduct, was found guilty and sentenced to 30 days in jail, which she is to start serving tomorrow. Those released on personal bond are Ken Heard of Denver; George Florman of Colorado Springs, Colo.; Frank Lozano of El Paso, Texas; Rick James of Salt Lake City, Utah; and Arthur Campbell of Louisville, Ky. ADAPT (266)

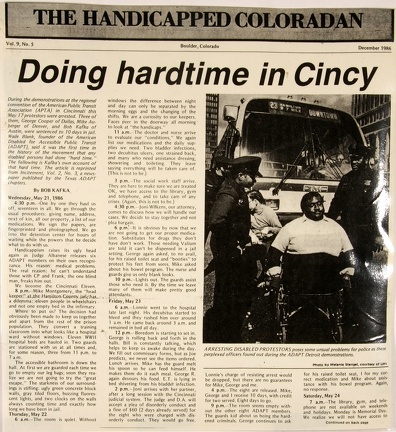

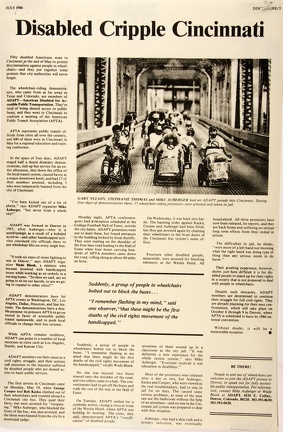

ADAPT (266)