- JazykAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Úvodní stránka / Alba / Štítky Atlantis Community + apartments

+ apartments 9

9

ADAPT (47)

ADAPT (47)

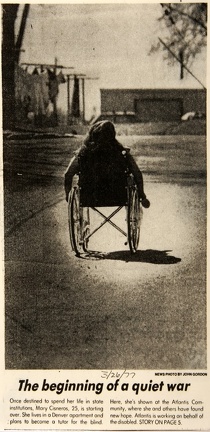

Rocky Mountain News March 26, 1977 News PHOTO by John Gordon: A small person (Mary Cisneros) with apparently no legs is seen from the back in wheelchair, wheeling through an empty lot. In the background is a clothes line with clothes hanging out to dry. [Headline] The beginning of a quiet war Once destined to spend her life in state institutions, Mary Cisneros, 25, is starting over. She lives in a Denver apartment and plans to become a tutor for the blind. Here, she's shown at the Atlantis Community, where she and others have found new hope. Atlantis is working on behalf of the disabled. Handicapped starting a 'quiet revolution' continued from.... ,,, the first time. For others, it means learning how to read and write. Mrs. Sue Sutherland, 23, is one of two women who tutor the Atlantis residents, using a special teaching machine developed by a University of Colorado professor. A staff of 27 persons, including some who were themselves rescued from institutional settings, provides attendant care. Their pay comes from the state and county attendant allowances of up to $217 per month to which many in Atlantis are entitled by law. A HOTLINE CONNECTS the housing units and the apartments of those no longer at Las Casitas, so residents can seek help quickly in emergencies. The job of manning the line is one of many tasks performed by the residents. Each is paid $50 a month, a figure arrived at because anything higher would oblige the recipients to involve themselves in red tape - and, in many cases, to lose the welfare payments they now receive. Most residents draw $184 a month in public assistance, most of it coming in the form of federal "SSI" payments. The rest comes from the state. From this, they pay $101 for room and board. Blank is the highest paid staff member. He gets about $8,000 a year from a combination of state and private grants. This leaves him eligible for food stamps. Administrator Mary Penland "gets paid when we can scrounge it up," and Kopp - who lives in Blank's house and has bought a third of it - hasn't been paid a dime of salary during his two years as co-director. Needless to say, Atlantis has made waves. lt has clashed with doctors who insist that the place for severely disabled persons is in an institution. And it has fought with those label people as "mentally retarded," saying the phrase is largely meaningless. "WE TOTALLY REFUSE to use that label here." says Blank. “We don't think the term is applicable to most young people. If they're retarded, it's socially retarded." Blank bubbles with excitement at the success stories of the people around him - those he proudly describes as “my circle of friends. “ And their affection for him is equally visible. There is Gary Van Lake. a 24-year-old Wyoming native who broke his neck in a 1973 car crash. Wyoming rehabilitation officials insisted he had no hope of returning to a normal life. "They told me I had reached my potential," he recalls. Coming to Denver to attend college, he wound up in a nursing home. Atlantis got him out and helped him get into Craig Hospital where he learned anew how to do things like go to the bathroom and drive a car. Now he has a specially equipped van, complete with an elevator for his electric wheelchair, and is engaged to marry in May. An outsider, viewing the rundown setting and the severity of the residents' physical problems, has to rely on their words and smiles to know how much their lives have improved. ONE TESTIMONIAL came from John Folks, 21, who has been paralyzed from the neck down since he was shot in June 1972. He breathes through a tube in his throat and uses a specially equipped telephone with a loudspeaker and a switch that he can trigger by moving his head to one side. Soon after Blank told how Folks had joined other Atlantis residents on a camping trip last summer. Folks explained how he felt about leaving the nursing home in which he lived for nine months before he came to Atlantis: “It's just like getting out of prison. lt is like starting over again. " Acknowledging that he and others at Atlantis “are somewhat egotistical" in their boasts of success, he adds: "We have to be to survive." But he also contends that the boasts are well-founded. For one thing, he notes, Atlantis has caught President Carter's fancy and could play a role in Carter's upcoming plans to revamp the welfare system. Last summer, when candidate Carter passed through Denver on the campaign trail, he met briefly with Atlantis officials. This week, two HEW aides from Washington came to Denver for a briefing on what Atlantis is doing. And a thick report, put together by Atlantis with an $82,500 federal grant, will go to Washington as Colorado's minority report at the White House Conference on Handicapped Individuals. The May event, planned when Gerald Ford was still president, is the first of its kind. lt is expected to set the stage for significant action by Congress to aid the nation's disabled citizens. The money for the Atlantis reports which was unveiled in February, came as a belated response to the original efforts of Blank and Kopp to get enough money so they could build Atlantis from the ground up. When the money came through in 1976, they knew it wouldn't be enough to get them out of Las Casitas. But they saw the value of a comprehensive report about the need of the disabled. ITS CONCLUSIONS are clear and blunt. Blunt as Wade Blanks words when he describes why Atlantis has the potential to be seen us model for the nation. “Our critics say all we have to offer is the slums," he noted a couple of days ago. "Yet 55 people are on our waiting list." "I think the nursing homes are going to have to start watching their words because the waiting list indicates, in essence, that these people would rather live in a slum than in a nursing home " NEXT: “We are demanding our rights." ADAPT (34)

ADAPT (34)

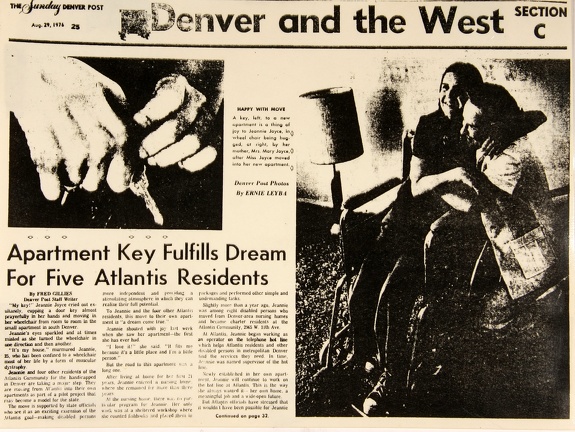

The Sunday Denver Post - August 29, 1976 [This article in continued in ADAPT 37, but the entire text is included here for easier reading] [Headline] Denver and the West Denver Post Photos by Ernie Leyba, Photo 1 (top left): Two hands gently hold a key. Photo 2 (on right): A young woman (Jeannie Joyce) in a manual wheelchair sits next to a floor lamp, and beside her kneels an older woman (Mary Joyce). Jeannie is looking up and her mother is looking forward to the right. Both are absolutely beaming. Captions (in middle) read: A key, left to a new apartment is a thing of joy to Jeannie Joyce, in wheel chair being hugged, at right, by her mother, Mrs. Mary Joyce, after Miss Joyce moved into her new apartment. [Subheading] Apartment Key Fulfills Dream for Five Atlantis Residents by Fred Gillies “My key!" Jeannie Joyce cried out exultantly, cupping a door key almost prayerfully in her hands and moving in her wheelchair room to room in the small apartment in south Denver. Jeannie's eyes sparkled and at times misted as she turned the wheelchair in one direction and then another. "It‘s my house," murmured Jeannie, 25, who has been confined to a wheelchair most of her life by a form of muscular dystrophy. Jeannie and four other residents of the Atlantis Community for the handicapped in Denver are taking a major step. They are moving from Atlantis into their own apartments as part of a pilot project that may become a model for the state. The move is supported by state officials who see it as an exciting extension of the Atlantis goal - making disabled persons more independent and providing a stimulating atmosphere in which they can realize their full potential. To Jeannie and the four other Atlantis residents, this move to their own apartment is “a dream come true." Jeannie shouted with joy last week when she saw her apartment - the first she has ever had. "I love it!" she said "it fits me because it's a little place and I'm a little person." But the road to this apartment was a long one. After living at home for her first 21 years, Jeannie entered a nursing home where she remained for more than three years. At the nursing home there was no particular program for Jeannie. Her only work was at a sheltered workshop where she counted fishhooks and placed them in packages and performed other simple and undemanding tasks. Slightly more than a year ago, Jeannie was among eight disabled persons who moved from Denver area nursing homes and became charter residents at the Atlantis Community, 2965 W. 11th Ave. At Atlantis, Jeannie began working as an operator on the telephone hot line which helps Atlantis residents and other disabled persons in metropolitan Denver find the services they need. In time, Jeannie was named supervisor of the hotline. Newly established in her own apartment, Jeannie will continue to work on the hot line at Atlantis. This is the way she always wanted it - her own home, a meaningful job and a wide-open future. But Atlantis officials have stressed that it wouldn't have been possible for Jeannie and the other four Atlantis residents to go out on their own without state support for a proposal advanced by Atlantis. That proposal was presented in June to Henry A. Foley, director of the Colorado Social Services Department. Foley's response was enthusiastic according to Wade Blank and Glen Kopp, codirectors at Atlantis. And as a result, Foley set up a pilot project which will go until the end of 1977. Simply stated, the project involves Atlantis' creation of an expanded staff of attendants to provide necessary services to the disabled in their apartments and homes as well as at Atlantis. And the state Medicaid fund will pick up the difference between government cost for attendant services and the amount of funds that actually are expended to provide the disabled with necessary care as certified by a physician. Blank explained that the government pays an average of $575 monthly for a severely disabled young adult living in a nursing home. If the disabled person moves into his own apartment he receives $186?[text is blurry] monthly from various governmental sources to pay for his rent, food, telephone and personal needs. And a county social services department may provide an additional $40 to $217 monthly to the disabled person for attendant services. But quite often, Blank said, even the maximum of $217 monthly doesn't cover the attendant services needed. And qualified attendants may not always be available, he noted. The cooperative program between Atlantis and the state might remedy those shortcomings and might cut government expenditures for the disabled substantially, Blank said. If the program is successful, Blank said, it could be expanded statewide for the disabled. Eventually, he added, the program might be extended to the state's elderly persons to keep them in their own homes and apartments, rather than placing them in a facility outside the home. Equally elated over the program is Mary Joyce, who is Jeannie's mother. Mrs. Joyce and her husband, Joseph, came to Denver last week from their home in Scarborough, Maine and were with Jeannie when she first viewed her apartment. “It's a pretty wonderful step" Mrs. Joyce said as she watched her daughter move in her wheelchair through the apartment. "We can't believe the strides she's made in the last two years with her determination to live on her own and take care of herself." To two other Atlantis residents, George Roberts and Don Clubb, the move to their own apartment is "a pretty big change." Born with cerebral palsy, George, now 28, was left as an infant at the door of an adoption agency in southern Colorado. George then was placed in a state home and training school where he remained for 21 years - a period he describes as "all my life." He also spent more than four years in a nursing home before being accepted at Atlantis in June 1975. Don, who soon will be 20, lost both legs as the result of a slide down a mountainside when he was six years old. For about 10 years, Don was in state home and training schools. And for the past five years, he has been in a nursing home. He, too, is confined to a wheelchair. Last week, as George and Don viewed the apartment they will share in north Denver, they seemed to invest the nearly empty rooms with an almost magical air. "It's wonderful," George said over and over. Carefully, he moved his wheelchair up to the electric stove and inspected the oven. In the bedroom, he was jubilant as he examined the heating and air-conditioning controls. And almost reverently, he opened and closed the sliding doors of a large bedroom closed. Don spoke quietly but with no less enthusiasm. "It's a very nice place - the first place of my own," he said. He smiled in the direction of the outdoor pool and said he swam very well and would teach George. Also preparing to move into an apartment they will share in south Denver are two other Atlantis residents, Carolyn Finnell, 33 and Nancy Anderson, 31. When she was 21, Nancy underwent surgery for removal of a brain tumor. For the next nine years, Nancy just sat in Denver area nursing homes unable to talk or walk, her body partially paralyzed. At that time, doctors said Nancy would be confined to nursing homes for the rest of her life and would never walk again. But since moving to Atlantis last summer, Nancy has been striving diligently in therapy sessions at Denver General Hospital. Working through the pain and the fatigue, she has learned to walk for up to 300 yards with the aid of a walker. And she has expanded her vocabulary to almost 10 words and is using a word machine in the new process of learning others. For Carolyn Finnell, who was born with cerebral palsy, there has been no easy or direct road to independent living. After finishing the ninth grade, Carolyn wasn't particularly encouraged to continue. But she was convinced and convinced others, that she was capable of further education. She obtained her GED, or general equivalency diploma, which is equivalent to a high school diploma. And she earned a degree in journalism at Metropolitan State College. But then there were the leaden days - four years in nursing homes "which didn't work out." Afterward, Carolyn came to Atlantis and her hope was reborn. Now, Carolyn is working in the Atlantis planning office and preparing plans for the education of the disabled. In her quarters at Atlantis last week, Carolyn said it was painful to leave so many behind when she left the nursing home. "But as we move out of Atlantis, it will make it possible for others to move in - and they never thought that was possible," she added. Looking to the future, Carolyn said she would like to return to school to obtain training so that she can tutor disabled persons who have never had an education. "There's a whole generation of disabled people who have been denied an education," she said. Carolyn stressed that she wasn't going to "wage a war against nursing homes I'm willing to live and let live." But she obviously was emotionally affected as she said, "I never realized until I got out of a nursing home that for a young person, it's a living death: You really have nothing to live for...nothing to do but just sit. Many disabled persons, Carolyn noted, attend Opportunity School and Boettcher School in Denver. "But I know for myself," she said, "I didn't have any faith in my ability to work." "But I've been involved in Atlantis planning," she said as a smile swept across her face and she threw out her arms, embracing the air. "I've gained faith in my ability and I'm started to get ambitious." Her next words came slowly, with triumphal emphasis: "I....just....feel....alive!" PHOTO: A woman (Carolyn Finnell) sits in her wheelchair. She is turned sideways, relaxed, facing the camera. Her arm is slung over the backrest, and she is beaming. ADAPT (32)

ADAPT (32)

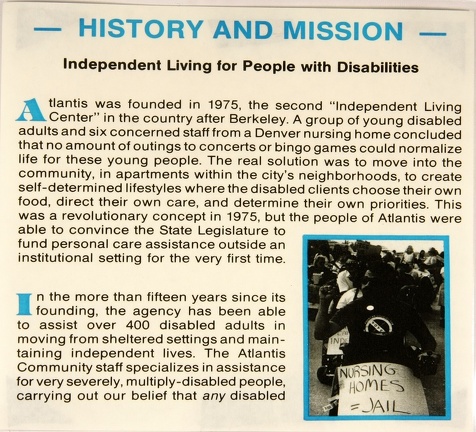

History and Mission Independent Living for People with Disabilities [This brochure continues in ADAPT 33, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] PHOTO by Tom Olin (bottom right): A man (George Roberts) in wheelchair raises the power fist with his right hand. He is carrying a sign that reads "Nursing Homes = Jail." Behind him a group of other wheelchair protesters are lining up. Atlantis was founded in 1975, the second “Independent Living Center” in the country after Berkeley. A group of young disabled adults and six concerned staff from a Denver nursing home concluded that no amount of outings to concerts or bingo games could normalize life for these young people. The real solution was to move into the community, in apartments within the city’s neighborhoods, to create self-determined lifestyles where the disabled clients choose their own food, direct their own care, and determine their own priorities. This was a revolutionary concept in 1975, but the people of Atlantis were able to convince the State Legislature to fund personal care assistance outside an institutional setting for the very first time. In the more than fifteen years since its founding, the agency has been able to assist over 400 disabled adults in moving from sheltered settings and maintaining independent lives. The Atlantis Community staff specializes in assistance for very severely, multiply-disabled people, carrying out our belief that any disabled person can live outside an institution, if s/he is willing to accept the risks and inconveniences in order to enjoy self-determination and liberty. To that end, the staff and clients are experts in helping with everything from finding an apartment to applying for benefits, from grocery shopping to weddings, from cooking training to camping trips. The assistance with daily living activities and the basic skills training and reinforcement offered are complemented by the trained and state-certified staff of home health aides and their supervisors who visit the clients at home as often as needed — usually several times a day. The people of Atlantis also offer other independent living services to people throughout the nation — ranging from information and referral services to assertiveness training and technical assistance. The city of Denver and the Atlantis Community have become a mecca for disabled people seeking an accessible environment and comprehensive services. PHOTO by Tom Olin (top left corner): 4 people in wheelchairs (left to right, Joe Carle, Diane Coleman, Bob Kafka and Mark Johnson) lead a march. Everyone is dressed in revolutionary war garb -- wigs, three cornered hats, jackets with braid on them. Over their heads is a large flag, the ADAPT flag. PHOTO (bottom right): An older man (Mel Conrardy) in a white jacket and pants, sits in a wheelchair on a lift at the front door of a bus. To his right on the side of the bus door it says RTD Welcome Aboard. Mel looks relaxed and is smiling.![ADAPT (27) (7169 návštěv) [Headline] Handicapped Pin Hope on Atlantis

By Sharon Sherman

Denver Post Staff Writer

The word... ADAPT (27)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/22/20160122153526-d347e9d0-sm.jpg) ADAPT (27)

ADAPT (27)

[Headline] Handicapped Pin Hope on Atlantis By Sharon Sherman Denver Post Staff Writer The word "activist' once scared a group of young Handicapped Denverites. But after almost two years of wheeling themselves onto picket lines, sitting through meetings with government agencies and speaking out about the problems of being shunted out of the mainstream of society, they agree that the term activist describes what they have become. And they are proud of it. "At least we're actively trying to do what we can instead of sitting back and wishing', is the way Carolyn Finnell, 31, sees the new role of many physically handicapped young people. [Subheading] Buses for Handicapped Carolyn, and others like her in the handicapped community, helped convince the Regional Transportation District to begin adding buses equipped for the handicapped. They have testified at various hearings about problems of the disabled. [TEXT UNREADABLE] They are among the principal planners of the Atlantis Community, a project which would offer the physically handicapped many types of residential living arrangements with services they need available nearby. Carolyn, who has cerebral play which confines her to a wheelchair and distorts her speech, said it was hard to "face speaking out" to rooms full of strangers, but that living with other young adults at Heritage House Nursing Home youth wing has "brought me out a lot." [Subheading] Stayed Inside Shell If Mike Smith, 20, had had his way, he would have stayed inside his shell of poetry writing, reading, and discussing philosophy and listening to music. "I don't like being in politics, but it seems that's the way we have to go,'' Mike explained. " I guess you have to lose a little to get a lot.'' Linda Chism, 27, believes that for the first time, there are enough young disabled people ready and willing to push themselves forward, to speak out, that there is a chance of changing the entire lifestyle of the handicapped. For Mike Smith, those changes may come too late to be enjoyed. [Subheading] Depressed, Angry Mike has muscular dystrophy, a fatal disease. He has spent the past five years in nursing homes, living in one where, at 15, he was punished for breaking rules and being sent to the locked ward for 24 hours at a time. Finally, lonely for friends his own age, depressed at watching his elderly roommate die of cancer, angry at rules which confined him to the small world of the nursing home, Mike attempted suicide. "Luckily, I had no idea how to go about it," he remembers. "I took 20 bowel softener pills and instead of dying just created an incredible mess." For Mike, as for Carolyn, the youth wing at Heritage House is infinitely better than what they had before. But, Mike points out, once the first door that closes any human being away from the rest of the world is opened, that human being will see other doors to open. So it has been for Carolyn, who counted fishhooks for five years in a sheltered workshop before someone recognized her potential. [Subheading] Wants Meaningful Job Now, with a degree in journalism from Community College behind her, Carolyn wants some other things she's not getting out of life. Things like a meaningful job, an apartment of her own where she won't have to keep half her belongings in boxes under the bed, the privacy to entertain friends. "I'm probably living a more active life than I ever have before", she said, explaining that she now edits the youth-wing newsletter and is learning braille so she can tutor blind students. Having come so far, Carolyn's not willing to stop here. Neither is Linda Chism, who has had crippling rheumatoid arthritis for 20 years. Linda has "suffered a lot of surgery and a lot of hard, hard therapy" to become fairly mobile. She has taken three years of courses in biology and psychology at the University of Colorado. She was even offered a full-time job. [Subheading] System Inflexible But the system doesn't allow even the disabled who are capable of supporting themselves to do so, Linda said. If she was paid even minimum wage, she would earn too much and would lose her Social Security benefits. But it would take much more than a minimum wage salary to pay living expenses plus the $150 a month it would cost her to get to work and back. In addition, she would no longer receive Medicaid assistance, and medical bills for someone in Linda's condition are enormous. "Who's going to pay a beginner with no experience that much money?" she asked. [Subheading] Innovative Projects For now, for these and other physically handicapped young adults, the boundaries of their world still don't go far beyond the nursing home walls. But those boundaries will expand dramatically if the young disabled can find support for two innovative projects. One is Project Normalization, a one year pilot study to find out what services young people in nursing homes need to live as normal a life as possible. The project would be conducted at the young wing of Heritage House and is estimated to cost $241,872. The state Department of Social Services has suggested that the pilot project be run by the Department of Physical Medicine of the University of Colorado Medical School. Members of the department now are investigating that possibility. [Subheading] Denied Normal Life "Disabled people are often denied any resemblance of a normal life," the project introduction says. "Because of the segregation they encounter, and the sheltered nature of their early lives, when they reach young adulthood they are incapable of functioning satisfactorily in society and so are banished to nursing homes where the repressive, nonstimulating and socially undemanding environment serves only to multiply their social inadequacies and further depersonalize them. As its creators see it, Project Normalization would begin to to prepare handicapped young adults for the kind of independent living they hope Atlantis will someday offer. [Subheading] Create a Community Atlantis is an ambitious project, planned by a group of both handicapped and able bodied persons, which would create a community of residential units surrounding a hub housing medical, rehabilitative employment, counseling, homemaker, transportation, food and social services. The goal of the community will be to "provide needed services while respecting the individual resident's freedom and privacy," according to the project booklet. For some of the prospective tenants of Atlantis, that goal can't be realized too soon. "I just sort of wish they'd hurry, " said Mike Smith. "Some of us have fatal diseases, you know, I only have two or three years to wait. "![ADAPT (26) (2451 návštěv) [Headline] Plan Drawn For 14 With Handicaps

A workshop to discuss a proposal to move 14 severely ... ADAPT (26)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/22/20160122153504-82c7e55d-sm.jpg) ADAPT (26)

ADAPT (26)

[Headline] Plan Drawn For 14 With Handicaps A workshop to discuss a proposal to move 14 severely handicapped adults from nursing homes to their own apartments will be sponsored by the Atlantis Community, Inc., at 1:30 pm, Wednesday, April 9 in room 807 at 1575 Sherman St. Host at the workshop will be Dr. Henry A. Foley, director of the State Department of Social Services which is monitoring Atlantis’ early-action program with the Denver Department of Health and Hospitals and the Denver Housing Authority. The workshop will focus on the specific roles and relationships of governmental and private agencies in meeting the needs of the seriously disabled. Atlantis Community, Inc., is a nonprofit organization working to create an independent-living facility in the Denver area for the severely handicapped.![ADAPT (24) (2270 návštěv) [Headline] Make Atlantis Work

With a newfound militance mixed with not a little nervousness and a... ADAPT (24)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/22/20160122153454-eeade242-sm.jpg) ADAPT (24)

ADAPT (24)

[Headline] Make Atlantis Work With a newfound militance mixed with not a little nervousness and a bit of tear, eight young persons recently moved into their first apartments. What made them different? All possess severe physical handicaps; all moved from the protective atmosphere of nursing homes which they had grown to find stifling. The little group moved into renovated apartments at Las Casitas complex in the 1200 block of Federal Boulevard. On July 1, they will be joined by six others. Atlantis Community, Inc., as they call their new venture was born of a small sum of "seed" money from Dr. Henry Foley, director of the state Department of Social Services, and matching federal funding. If the program works—if the young people are able to successfully live in a semi-protected, semi-free community environment—it is hoped that it will be expanded. ADAPT (20)

ADAPT (20)

Denver Post, 1975 PHOTO. Denver Post photos by Ernie Leyba: A slim woman and man in a manual wheelchair are surrounded by laundry they are folding and stacking. They look over their shoulders as the man shakes hands with a man in a dark suit (Governor Lamm) who is talking with another standing man with longish blonde hair (Wade Blank). Caption reads: Gov. Dick Lamm, left,and Director Wade Blank visit laundry. Handicapped "hot line" has been set up in laundry, which is also office. [Headline] Lamm Tours Community of Handicaps By Patrick A. McGuire Denver Post Staff Writer Fourteen handicapped persons who once lived in nursing homes, but now enjoy a high degree of independence in their own community, welcomed Gov. Dick Lamm to their homes Tuesday for a special tour. Their home, the Atlantis Community, occupies seven apartments and a laundry room in a Denver Housing project at W. 11th and Federal Boulevard. With federal and state funds, the 14 residents and 12 staff aides have remodeled the apartments so that wheel chairs move freely through hallways and down ramps. With a state grant they have set up a handicapped “hot line” in the laundry room that doubles as an office. As many as 70 times daily, handicapped persons across the city and state call seeking information on services. Lamm encouraged Atlantis to seek state funds for the project through the Colorado Social Services Department. He went to the community Tuesday, ostensibly to see how state money was being used, but admitted in an interview that he had other reasons. “During my campaign," he said, “that whole walk across the state was very intense. It was a gimmick, too, I’ll be the first to admit that. “But I stayed at some places and saw some people like these. I was trying to sensitize myself. You know, it’s the easiest thing in the world to forget people like these.” He said he wanted to make sure he didn’t forget them. Lamm went from apartment to apartment with Wade Blank, Atlantis executive director, inspecting the homes and shaking hands with the delighted residents. For most of their lives, the residents have lived in nursing homes, depending on them for medical care and a social life. Barry Rosenberg, a member of the Atlantis board of directors, told Lamm, “So many handicapped are born with a sense of guilt, because they’re different. We’re trying to turn them around and give them some hope. Atlantis residents Blank said, draw on existing city services for medical care and social services.He estimated that it costs $225 a month less, per person, to live at Atlantis than in a nursing home. The city is planning to lower the curbing along the Atlantis boundary on Federal Boulevard, so the wheel-chaired residents easily can cross the street to stores and restaurants. Lamm praised the Atlantis staff as “dedicated people who are trying to make sure a few other fine human beings are cared for."![ADAPT (14) (1650 návštěv) The Denver Post - Tuesday October 26, 1976

[Headline] Housing Sought By Handicapped

Seven memb... ADAPT (14)](_data/i/upload/2016/02/21/20160221164523-4e5bcebf-sm.jpg) ADAPT (14)

ADAPT (14)

The Denver Post - Tuesday October 26, 1976 [Headline] Housing Sought By Handicapped Seven members of the Atlantis Community for the handicapped in Denver have been moved into their own apartments throughout the Denver area, but more apartments are needed, an Atlantis spokesman said Tuesday. Wade Blank, Atlantis codirecter, said the move of the physically disabled into their own apartments increased the independence that Atlantis is attempting to foster among the disabled. One or two-bedroom apartments are needed for Atlantis residents who are confined to wheel chairs, Blank said. The apartments may be furnished or unfurnished, he added. The Atlantis staff, on duty 24 hours daily, visits members of its community who are in their own apartments to make sure that their daily living needs are met. Apartments also are sought for the disabled who are facing loss of their independent living situation unless they can receive services such as Atlantis provides, Blank said. Apartments for the disabled, Blank said, should have doors at least 28 inches wide, an entrance that has no steps or just one or two steps that can be fitted with one of Atlantis' portable ramps. Interested apartment owners, landlords or managers may call Atlantis at 893-8040 between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. weekdays. An Atlantis member will meet with the landlord, and apartments that are suitable will be listed in an apartment guide for the disabled, Blank said. ADAPT (12)

ADAPT (12)

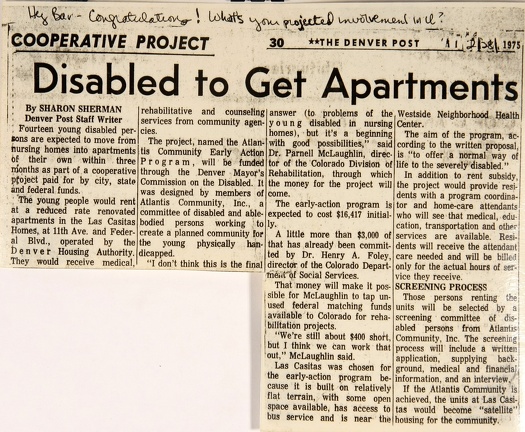

The Denver Post 2/28/1975 (Handwritten note at top of the page: Hey Bar - Congratulations! What's your projected involvement in it?) [Headline] Cooperative Project Disabled to Get Apartments By Sharon Sherman, Denver Post Staff Writer Fourteen young disabled persons are expected to move from nursing homes into apartments of their own within three months as part of a cooperative project paid for by city, state and federal funds. The young people would rent at a reduced rate renovated apartments in the Las Casitas Homes, at 11th Ave. and Federal B1vd., operated by the Denver Housing Authority. They would receive medical, rehabilitative and counseling services from community agencies. The project, named the Atlantis Community Early Action Program, will be funded through the Denver Mayor's Commission on the Disabled. It was designed by members of Atlantis Community, Inc., a committee of disabled and able-bodied persons working to create a planned community for the young physically handicapped. "I don't think this is the final answer (to problems of the young disabled in nursing homes), but it's a beginning with good possibilities,” said Dr. Parnell McLaughlin, director of the Colorado Division of Rehabilitation, through which the money for the project will come. The early-action program is expected to cost $16,417 initially. A little more than $3,000 of that has already been committed by Dr. Henry A. Foley, director of the Colorado Depart Social Services. That money will make it possible for McLaughlin to tap unused federal matching funds available to Colorado for rehabilitation projects. "We're still about $400 short, but I think we can work that out,” McLaughlin said. Las Casitas was chosen for the early-action program because it is built on relatively flat terrain, with some open space available, has access to bus service and is near the Westside Neighborhood Health Center. The aim of the program, according to the written proposal, is “to offer a normal way of life to the severely disabled.” In addition to rent subsidy, the project would provide residents with a program coordinator and home-care attendants who will see that medical, education, transportation and other services are available. Residents will receive the attendant care needed and will be billed only for the actual hours of service they receive. [Subheading] SCREENING PROCESS Those persons renting the units will be selected by a screening committee of disabled persons from Atlantis Community, Inc. The screening process will include a written application, supplying background, medical and financial information, and an interview. If the Atlantis Community is achieved, the units at Las Casitas would become “satellite" housing for the community.