- ภาษาAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

หน้าหลัก / อัลบั้ม / ผลการค้นหา 6

วันที่โพสต์ / 2016

« 2015

มกราคม

กุมภาพันธ์

มีนาคม

เมษายน

พฤษภาคม

มิถุยายน

กรกฎาคม

สิงหาคม

กันยายน

ตุลาคม

พฤษจิกายน

ธันวาคม

ทั้งหมด

![ADAPT (208) (12184 visits) The San Diego Union March 2, 1986, page A3

The West [section of newspaper]

Drawing of Mr Louv'... ADAPT (208)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/08/20160108130058-7eec73bc-me.jpg) ADAPT (208)

ADAPT (208)

The San Diego Union March 2, 1986, page A3 The West [section of newspaper] Drawing of Mr Louv's head: White, youngish, short dark hair parted on side and glasses. [Headline] Transportation news for handicapped ‘a nightmare’ By Richard Louv The WHEELCHAIRS are rolling. On Jan. 16, in Dallas, handicapped demonstrators decrying "taxation without transportation," chained themselves to public buses, forcing traffic detours for nearly six hours. In downtown Los Angeles, last Oct 7, more than 200 people in wheelchairs rolled down the middle of Wilshire Boulevard to protest the policies of the American Public Transit Association. In San Antonio last April, 60 handicapped people staged a four-hour protest at the city's public transit offices, causing 90 nervous bus company employees to lock themselves in their offices for an hour until the transit association agreed to meet the demonstrators. And on Feb. 13, Houston police arrested eight demonstrators in wheelchairs and carted them off to jail in lift-equipped police vans. Their sentencing is tomorrow. and a representative of the Denver-based American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit told me that if the protesters “spend weeks in jail, it will be like when Martin Luther King went to jail in Birmingham. People will realize we're not just out playing in the street" What's going on here? The disabled~rights movement isn't new, of course. It began in Berkeley in the late 60s, and ultimately resulted in a government shift from segregating handicapped people to "mainstreaming" them into the rest of society. According to Cyndi Jones, publisher of San Diego-based Mainstream, a national magazine for the “able-disabled," some of the first generation leaders "got co-opted by government jobs, and frustration for the rest of us has been growing." A raft of laws were passed during the 1970s, but the laws. says Jones. still haven't been fully implemented. “The Rehabilitation Act promised disabled people equal access to public transportation facilities and education and employment. In education. the news has been good, but transportation is a nightmare." IN 1981, CONTENDING THAT putting lifts on buses was an unrealistic expense, the American Public Transit Association sued the federal government and won. Most cities stopped deploying the mechanical lifts that enable people using wheelchairs, walkers and crutches to board buses. The favored transportation method, at least among municipal officials, became small, subsidized "dial-a-ride" vans. "That's like putting us back in segregated schools," says Jones. The disability groups have a number of other complaints, some of them affecting many more people — lack of housing, attended care, airplane facilities. But what it has come down to is the symbol of lifts. While some disabled people are satisfied with the dial-a-ride approach, Jones says "taking a van service can cost you $60 to get to work and back. You have to call and reserve a ride — sometimes days in advance, and these services can't always guarantee a specific arrival time or even take you home. As a result, a lot of us can't afford to work, or we just stay home." California still requires lifts on all new buses, but Jones contends that the transit companies can develop some creative delaying tactics. Roger Snoble, the San Diego Transit Corp.'s general manager, agrees with her. "Some cities," he says, "don't care whether the lifts work once they put them on. They just let them go, and then say the lifts don't work." Jones, by the way, gives relatively high marks to San Diego's bus system; not so to the trolley. which she calls “miserable for handicapped people." As she sees it, a new generation of leaders in the disabled~rights movement is just now coming of age. They have some powerful opponents —— with some powerful statistics. Jim Mills, chairman of the Metropolitan Transit Development Board, has pointed out that in Los Angeles the average cost per ride of the various dial-a-ride systems “is $6.22, while the costs associated with a one-way trip on a bus for a person in a wheelchair is $300." And in a recent interview, Colorado Gov. Richard Lamm told me, "I think it is a myopic use of capital to try to put a lift on every bus in America. It costs the St. Louis bus system $700 per ride to maintain lifts." But Roger Snoble says it costs San Diego far less — $166 per ride (as of a year ago, "the last time we checked, and we expect the cost to continue to decline because of dramatically improving technology." And when I mentioned Lamm's figures to Dennis Cannon, the chief federal watchdog for the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Transit Compliance Board, he said, “Lamm's figures are at least six or seven years old, and wrong. These same figures get used a lot by lift opponents, but they're based on one of the very first generations of lifts, which were poorly administered and poorly installed by St. Louis during one the worst winters in Missouri history." He points out that Seattle, with one of the best bus systems in the nation, has managed to get the per-ride costs down to $5 or $10, depending on the amount of ridership. And Denver has decreased its lift failures from 25 a day to five within the last year. WITH ADVANCES LIKE this, combined with the increasing demands from disabled groups, a number of cities have decided that the lifts make economic sense — maybe not in this decade, but soon. "What's about to hit is a wave of people who expect to have equal access, the children of the mainstreaming movement," says Jones. During the past decade, government and society encouraged disabled people to work independently, and now that generation will be at bus stops and trolley stations all over the country, waiting to go to work. With them will be aging baby boomers, a giant crop of potentially disabled seniors. "Only one~third of the disabled population is employed. but two-thirds of disabled people are not receiving any kind of benefits," says Andrea Farbman, a spokeswoman for the National Council on the Handicapped. “Still. we're spending huge amounts of money keeping people unemployed — $60 billion dollars a year, but only $2 billion going to rehabilitation and special education." One rough estimate, says Farbman, is that 200,000 handicapped people would enter the work force if the travel barriers were eliminated. adding as much as $1 billion in annual earnings to the economy. The tragedy is this: While politicians wrangle over the costs of bus lifts, nobody has studied how much money could be saved in government benefits, and how much could be gained through taxes and added national productivity if more handicapped Americans were employed. ADAPT (135)

ADAPT (135)

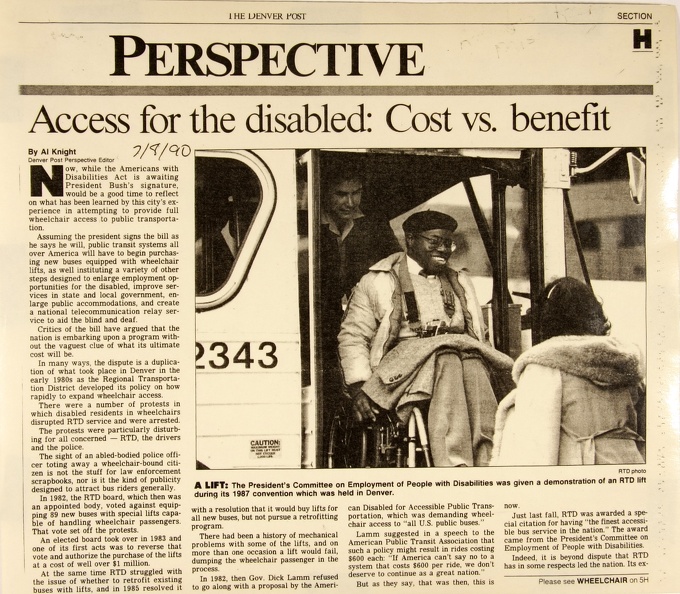

The Denver Post 7/8/90 [This article continues in ADAPT 138, but the entire story has been included here for easier reading] Perspective Access for the disabled: Cost vs. benefit Photo by RTD staff: A smiling African American man in a manual wheelchair, wearing a beret and with a sports coat over his lap is being helped to board a city bus by the driver, who is behind him. In front of the lift a woman stands waiting to board. Caption reads: A LIFT: The President's Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities was given a demonstration of an RTD lift during its 1987 convention which was held in Denver. By Al Knight Denver Post Perspective Editor Now, while the Americans with Disabilities Act is awaiting President Bush’s signature, would be a good time to reflect on what has been learned by this city's experience in attempting to provide full wheelchair access to public transportation. Assuming the president signs the bill as he says he will, public transit systems all over America will have to begin purchasing new buses equipped with wheelchair lifts, as well instituting a variety of other steps designed to enlarge employment opportunities for the disabled, improve services in state and local government, enlarge public accommodations, and create a national telecommunication relay service to aid the blind and deaf. Critics of the bill have argued that the nation is embarking upon a program without the vaguest clue of what its ultimate cost will be. In many ways, the dispute is a duplication of what took place in Denver in the early 1980s as the Regional Transportation District developed its policy on how rapidly to expand wheelchair access. There were a number of protests in which disabled residents in wheelchairs disrupted RTD service and were arrested. The protests were particularly disturbing for all concerned — RTD, the drivers and the police. The sight of an abled-bodied police officer toting away a wheelchair-bound citizen is not the stuff for law enforcement scrapbooks, nor is it the kind of publicity designed to attract bus riders generally. In 1982, the RTD board, which then was an appointed body, voted against equipping 89 new buses with special lifts capable of handling wheelchair passengers. That vote set off the protests. An elected board took over in 1983 and one of its first acts was to reverse that vote and authorize the purchase of the lifts at a cost of well over $1 million. At the same time RTD struggled with the issue of whether to retrofit existing buses with lifts, and in 1985 resolved it with a resolution that it would buy lifts for all new buses, but not pursue a retrofitting program. There had been a history of mechanical problems with some of the lifts, and on more than one occasion a lift would fail, dumping the wheelchair passenger in the process. In 1982, then Gov. Dick Lamm refused to go along with a proposal by the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, which was demanding wheelchair access to “all U.S. public buses." Lamm suggested in a speech to the American Public Transit Association that such a policy might result in rides costing $600 each: “If America can't say no to a system that costs $600 per ride, we don't deserve to continue as a great nation.“ But as they say, that was then, this is now. Just last fall, RTD was awarded a special citation for having "the finest accessible bus service in the nation." The award came from the President's Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities. Indeed. it is beyond dispute that RTD has in some respects led the nation. Its experience in developing its current fleet of buses was the prime example used by congressional supporters of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In addition, it is a fact that RTD was the first agency to order its over-the-road buses equipped with lifts. Until RTD's first order, these larger vehicles had been built without lifts. The RTD program hasn’t been accomplished without significant expense. It has cost about $8 million for the lift equipment and millions more for parts, maintenance and training. But the latest figures show per-ride costs are far below the $600 figure mentioned by Lamm. The lifts cost about $13,000 a copy. Because the life of a bus normally is calculated at 12 years, this works out to a little more than $1,000 a bus per year. To this must be added the maintenance cost, which has been dropping each year. As recently as 1985 the cost of maintaining an individual lift was $1,798. This year the average is just over $500. Even without the retrofitting program rejected by the board in 1985, RTD has managed to increase greatly its percentage of lift-equipped buses. In 1985, only 54 percent of buses were so equipped. This year 81 percent are. In recent years, disabled ridership has gone up sharply. In 1982 it was just over 9,000 wheelchair boardings, but last year it reached an estimated 45,000. According to RTD figures, the per-ride cost may have reached $80 in 1984, but with the increase in ridership and the drop in maintenance cost, the cost per ride now has dropped to about $19 a ride, according to the latest calculations. What is not known is how many of Denver’s disabled community actually are served by the lifts. In the mid-1980s, it was estimated that only a few hundred wheelchair-bound residents were regular bus riders. Even as RTD has fitted new buses with the lifts, demands for its HandyRide service have continued to increase. This door-to-door service is available to both the elderly and the handicapped. Some of its wheelchair passengers could be served by regular buses, but many others are unable to get to the bus stop and therefore require the HandyRide service. Precise calculations aren’t available, but it is estimated the cost per ride for using the van service is about $50. Lamm, contacted this week, said he basically hasn’t changed his position on the issue. He said the $600 figure he used in 1982 was based on the experience of the St. Louis bus company. “To govern is to choose," he said, "and I don't believe this nation should make every bus wheelchair-accessible. Should the handicapped be provided transportation? Of course, but it should be provided in the most cost-effective way possible.” Lamm mentioned the expensive elevator system that is a part of the Washington, D.C., subway system as an example of a method that isn't cost-effective. The Denver experience does indicate that the costs of accommodating the wheelchair-bound citizen may not be an endlessly upward spiral. But the key indicator that needs watching is the number of passengers using the service. The taxpayers, the RTD board and staff members clearly have done their part. The wheelchair service is now available on nearly every bus, yet ridership has flattened out. The estimate of 45,000 wheelchair passengers for 1989 is just a few hundred higher than the 1986 level. More persons must be encouraged to use the service. Now that maintenance costs are down, the only way to decrease the still-considerate per-ride cost is to increase the number of passengers using the lifts. The most compelling case the disabled community can make for greater access is to demonstrate an even higher usage of the existing facilities. Highlighted Text: Even without the retrofitting program rejected by the board in 1985, RTD has managed to increase greatly its percentage of lift-equipped buses. In 1985, only 54 percent of buses were so equipped. This year 81 percent are. Photo by The Denver Post/Duane Howell: A slight woman in a wheelchair is being escorted out by two uniformed and one plainclothes police. She is telling one of the officers something and they are all listening with slight smiles on their faces. Behind this group a man in a wheelchair is following, escorted by another police officer and behind them three other policemen stand guard. Caption reads: PROTEST: An unidentified demonstrator at the Regional Transportation District office was escorted out during a 1982 protest over the purchase of new buses. ADAPT (52)

ADAPT (52)

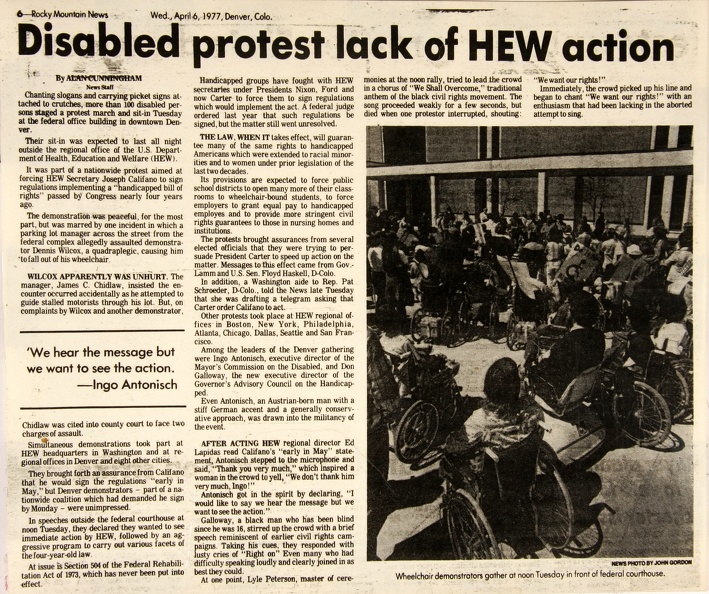

Rocky Mountain News, Wed., April 6, 1977, Denver, Colo. PHOTO by John Gordon: A large crowd of protesters, many in wheelchairs, are gathered outside a building. All are facing the building and a couple carry signs. Caption reads: Wheelchair demonstrators gather at noon Tuesday in front of federal courthouse. [Headline] Disabled protest lack of HEW action By Alan Cunningham Chanting slogans and carrying picket signs attached to crutches, more than 100 disabled persons staged a protest march and sit-in Tuesday at the federal office building in downtown Denver. Their sit-in was expected to last all night outside the regional office of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) It was part of a nationwide protest aimed at forcing HEW Secretary Joseph Califano to sign regulations implementing a "handicapped bill of rights" passed by Congress nearly four years ago. The demonstration was peaceful, for the most part, but was marred by one incident in which a parking lot manager across the street from the federal complex allegedly assaulted demonstrator Dennis Wilcox, a quadraplegic, causing him to fall out of his wheelchair. Wilcox apparently was unhurt. The manager, James C. Chidlaw, insisted the encounter occurred accidentally as he attempted to guide stalled motorists through his lot. But, on complaints by Wilcox and another demonstrator, Chidlaw was cited into county court to face two charges of assault. Simultaneous demonstrations too part at HEW headquarters in Washington and at regional offices in Denver and eight other cities. They brought forth an assurance from Califano that he would sign the regulations “early in May," but Denver demonstrators — part of a nationwide coalition which had demanded he sign by Monday - were unimpressed. In speeches outside the federal courthouse at noon Tuesday, they declared they wanted to see immediate action by HEW, followed by an aggressive program to carry out various facets of the four-year-old law. At issue is Section 504 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which had never been put into effect. Handicapped groups have fought with HEW secretaries under Presidents Nixon, Ford and now Carter to force them to sign regulations which would implement the act. A federal judge ordered last year that such regulations be signed, but the matter still went unresolved. The law when it takes effect, will guarantee many of the same rights to handicapped Americans which were extended to racial minorities and to women under prior legislation of the last two decades. Its provisions are expected to force public school districts to open many more of their classrooms to wheelchair-bound students, to force employers to grant equal pay to handicapped employees and to provide more stringent civil rights guarantees to those in nursing homes and institutions. The protests brought assurances from several elected officials that they were trying to persuade President Carter to speed up action on the matter. Messages to this effect came from Gov.Lamm and U.S. Sen. Floyd Haskell, D-Colo. In addition, a Washington aide to Rep. Pat Schroeder, D-Colo., told the News late Tuesday that she was drafting a telegram asking that Carter order Califano to act. Other protests took place at HEW regional offices in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Seattle and San Francisco. Among the leaders of the Denver gathering were Ingo Antonisch, executive director of the Mayor's Commission on the Disabled, and Don Galloway, the new executive director of the Governor's Advisory Council on the Handicapped. Even Antonisch, an Austrian-born man with a stiff German accent and a generally conservative approach, was drawn into the militancy of the event. After acting HEW regional director Ed Lapidas read Califano's "early in May" statement, Antonisch stepped to the microphone and said, "Thank you very much," which inspired a woman in the crowd to yell, "We don't thank him very much, Ingo!" Antonisch got in the spirit by declaring, "I would like to say we hear the message but we want to see the action." Galloway, a black man who has been blind since he was 16, stirred up the crowd with a brief speech reminiscent of earlier civil rights campaigns. Taking his cues, they responded with lusty cries of “Right on" Even many who had difficulty speaking loudly and clearly joined in as best they could. At one point, Lyle Peterson, master of ceremonies at the noon rally, tried to lead the crowd in a chorus of "We Shall Overcome," traditional anthem of the black civil rights movement. The song proceeded weakly for a few seconds, but died when one protestor interrupted, shouting: "We want our rights!" Immediately, the crowd picked up his line and began to chant "We want our rights!" with an enthusiasm that had been lacking in the aborted attempt to sing. BOXED TEXT: We hear the message but we want to see the action. -- Ingo Antonisch ADAPT (41)

ADAPT (41)

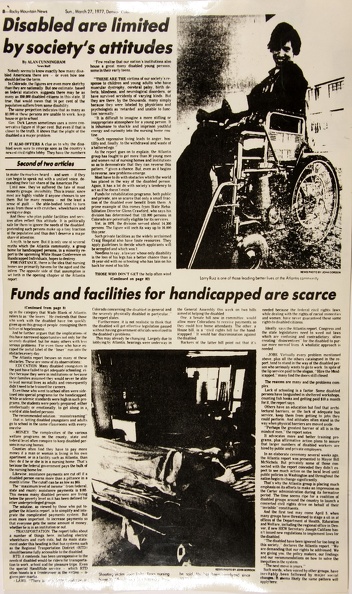

Rocky Mountain News Sunday March 27, 1977 Disabled are limited by society's attitudes By Alan Cunningham PHOTO by John Gordon, News: A young man (Larry Ruiz) sits in a wheelchair in front of a building. The shot shows his whole body and wheelchair and is looking up at Larry's smiling face. (For those who knew Larry, it's a classic Larry smile.) Caption reads: Larry Ruiz is one of those leading better lives of the Atlantis community. Nobody seems to know exactly how many disabled Americans there are - or even how one should define them. In Colorado, the figures are even more sketchy than they are nationally. But one estimate, based on federal statistics, suggests there may be as many as 350,000 disabled citizens in this state. If true, that would mean that 14 percent of the population suffers from some disability. The same projection indicates that as many as 83,000 of these persons as unable to work, keep house or go to school. Gov. Dick Lamm sometimes uses a more conservative figure of 10 percent. But even if that is closer to the truth, it shows that the plight of the disabled is a major problem. It also offers a clue as to why the disabled seem sure to emerge soon as the country's newest civil rights lobby. The have the numbers to make themselves heard - and seen - if they can begin to speak out with a unified voice, demanding their fair share of the American Pie. Until now, they've suffered the fate of most minority groups: invisibility. This is ironic, since most are highly visible if anyone chooses to see them. But for many reasons - not the least a sense of guilt - the able-bodied tend to turn away from those with crutches, wheelchairs and seeing eye dogs. And those who plan public facilities and services often reflect this attitude. It is politically safe for them to ignore the needs of the disabled pretending such persons make up a tiny fraction of the population and thus don't deserve a major share of attention. A myth to be sure. But it is only one of several myths which the Atlantis community, a group home for handicapped persons, in a minority report to the upcoming White House Conference on Handicapped individuals, hopes to destroy. For instance, there is the idea that nursing homes are primarily heavens for the aged and the infirm. The opposite side of that assumption is set forth in the opening chapter of the Atlantis report. Few realize that our nation's institutions also house a great many disabled young persons, some in their early teens. THESE ARE THE victims of our society's response to children and young adults who have muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, birth defects, blindness, and neurological disorders, or have survived accidents of varying kinds. But they are there by the thousands, many simply because they were labeled by physicians and psychologists as "retarded" and unable to function normally. It is difficult to imagine a more stifling or inappropriate atmosphere for a young person. It is inhumane to shackle and imprison youthful energy and curiosity into the nursing home routine. Such repressive living leads to anger, hostility and finally to the withdrawal and waste of a battered ego. As the report goes on to explain, the Atlantis group has fought to get more than 30 young men and women out of nursing homes and institutions so as to demonstrate that they can reverse this pattern if given a chance. But, even as it begins to reverse, new problems emerge. Most have to do with obstacles which the world has placed in the way of the disabled person. Again, it has a lot do with society's tendency to act as if he doesn't exist. Funds for rehabilitation programs, both public and private, are so scarce that only a small fraction of the disabled ever benefit from them. A prime example of this comes from State Rehabilitation Director Glenn Crawford, who says his division has determined that 135,000 persons in Colorado are potentially eligible for its services. Yet, in 1976, the division served about 14,300 persons. The figure will inch its way up to 16,000 this year. Such private facilities as the widely acclaimed Craig Hospital also have finite resources. They apply guidelines to decide which applicants will be accepted and which won't. Needless to say, a lawyer whose only disability is the loss of his legs has a better chance than a 19-year-old with no schooling who has lain on his back for most of his life. Funds and facilities for handicapped scarce Those who don't get the help often wind up in the category that Wade Blank of Atlantis refers to as "the losers." He contends that those who work with the disabled have too quickly given up on this group of people consigning them to lives of hopelessness. And he further argues that the implications of this have narrowed opportunities not only for the severely disabled, but for many others with less serious problems. For even those who have escaped the awful label of the "loser" run into obstacles every day. The Atlantis report focuses on many of these obstacles. These are some of the observations: EDUCATION. Many disabled youngsters in the past have failed to get adequate schooling either because they were in institutions or because their families assumed they would never be able to lead normal lives as adults and consequently didn't need to be trained for careers. Even those who went to school often were sidelined into special programs for the handicapped. While academic standards were high in such programs, the students were poorly prepared either intellectually or emotionally, to get along in a world of able-bodied persons. The recommended solution, "mainstreaming"- that is, letting disabled youngsters and adults go to school in the same classroom with everyone else. MONEY. The complexities of the various welfare programs on the county, state and federal level often conspire to keep disabled persons in nursing homes. Counties often find they have to pay more money if a man or woman is living in his own apartments, or in a facility, such as Atlantis, than they do if he or she is in a nursing home. That's because the federal government pays the bulk of the nursing home fee. Likewise, assistance payments are cut off if a disabled person earns more than a pittance in a month's time. The cutoff can be as low as $65. The "maximum level of income"from federal state and county assistance payments is $185. This means many disabled persons are living below the poverty level as it has been defined for other underprivileged groups. The solution as viewed by those who put together the Atlantis report, is to simplify and integrate the complicated payments system. But even more important, to increase payments so that everyone gets the same amount of money whether he is in an institution or out. TRANSPORTATION. The report talks about a number of things here including electric wheelchairs and curb cuts, but is main statement under this heading is that bus systems such as the Regional Transportation District (RTD) should become fully accessible to the disabled. RTD, it contends, has been unresponsive to the needs of disabled would be riders for transportation to work, school and for pleasure trips. Even the special HandiRide service - which RTD often boasts is a frontrunner in the nation - is given poor marks. LAWS. [not legible...] Colorado concerning the disabled in general and the severely physically disabled in particular, the report states. Furthermore, it is not realistic to think that the disabled will get effective legislation passed without having government officials sensitized to the disabled's problems. This may already be changing. Largely due to lobbying by Atlantis, hearings were underway in the General Assembly this week on two bills aimed at helping the disabled. One, a Senate bill now in committee, would allow more Coloradans to receive payments so they could hire home attendants. The other, a House bill, is a "civil rights bill for the handicapped." It would bar discrimination against the disabled. Backers of the latter bill point out that it's needed because the federal civil rights laws, while dealing with the rights of racial minorities and women, have never guaranteed these same rights to disabled citizens. Idealy, says the Atlantis report, Congress and the state legislatures need to weed out laws which are confusing and contradictory, often creating "disincentives"for the disabled to pursue more normal lives. A wholistic approach is needed. JOBS. Virtually every problem mentioned above, plus all the others catalogued in the report, tend to stand in the way of the disabled person who seriously wants to go to work in spite of the lip service paid to the slogan, "Hire the handicapped," many find the doors still closed. The reasons are many and the problems complex. Lack of schooling is a factor. Some disabled persons have languished in sheltered workshops, counting fish hooks and getting paid $10 a month for it, the report says. Others have an education but find that architectural barriers, or the lack of adequate bus service, keep them from getting to jobs they could perform. And attitudes often stand in the way when physical barriers are moved aside. "Perhaps the greatest barrier of all is in the minds of men," the report notes. It advocates more and better training programs, plus affirmative action plans to assure that larger numbers of disabled workers are hired by public and private employers. In an elaborate ceremony several weeks ago, the Atlantis report was presented to Mayor Bill McNichols. But privately some of those connected with the report conceded they didn't expect to see much action on the local level until public policies in Washington and throughout the nation begin to change significantly. That's why the Atlantis group is placing much emphasis on its efforts to make an impression on the Carter administration during its formative period. The time seems ripe for a coalition of disabled groups around the country to launch a concerted civil rights drive on behalf of their "invisible" constituents. And the first test may come April 5, when many groups have threatened to stage a sit-in at offices of the Department of Health Education and Welfare, including the regional office in Denver, if new HEW Secretary Joseph Califano hasn't issued new regulations to implement laws for the disabled. "The disabled have been ignored far too long in this society," declares the Atlantis report. "We are demanding that our rights be addressed. We are giving you, the policy makers, our findings and recommendations on how to solve the inequities in the system. "The next is yours." Such words, when voiced by other groups, have inevitably been followed by major social changes. It seems likely the same pattern will apply here. PHOTO by John Gordon, News: A man lies in a hospital bed, covered by sheets. Photo is very dark and hard to make out. Caption reads: Shooting victim [unreadable] from nursing home [unreadable] he said [unreadable] has been paralyzed since [unreadable].![ADAPT (21) (1626 visits) PHOTO [no credit available]: A small woman (Debby Tracy) in a fairly large manual wheelchair, eye gl... ADAPT (21)](_data/i/upload/2016/01/22/20160122153409-b7817d89-me.jpg) ADAPT (21)

ADAPT (21)

PHOTO [no credit available]: A small woman (Debby Tracy) in a fairly large manual wheelchair, eye glasses, a paisley dress and sneakers, smiles and looks down toward the floor. Behind her two men and a woman are standing and also looking down and smiling. Caption reads: FROM LEFT, SAM SANDOS, RESIDENT DEBORAH TRACY AND LAMM. Lamm encouraged Atlantis residents to seek state funds for project. ADAPT (20)

ADAPT (20)

Denver Post, 1975 PHOTO. Denver Post photos by Ernie Leyba: A slim woman and man in a manual wheelchair are surrounded by laundry they are folding and stacking. They look over their shoulders as the man shakes hands with a man in a dark suit (Governor Lamm) who is talking with another standing man with longish blonde hair (Wade Blank). Caption reads: Gov. Dick Lamm, left,and Director Wade Blank visit laundry. Handicapped "hot line" has been set up in laundry, which is also office. [Headline] Lamm Tours Community of Handicaps By Patrick A. McGuire Denver Post Staff Writer Fourteen handicapped persons who once lived in nursing homes, but now enjoy a high degree of independence in their own community, welcomed Gov. Dick Lamm to their homes Tuesday for a special tour. Their home, the Atlantis Community, occupies seven apartments and a laundry room in a Denver Housing project at W. 11th and Federal Boulevard. With federal and state funds, the 14 residents and 12 staff aides have remodeled the apartments so that wheel chairs move freely through hallways and down ramps. With a state grant they have set up a handicapped “hot line” in the laundry room that doubles as an office. As many as 70 times daily, handicapped persons across the city and state call seeking information on services. Lamm encouraged Atlantis to seek state funds for the project through the Colorado Social Services Department. He went to the community Tuesday, ostensibly to see how state money was being used, but admitted in an interview that he had other reasons. “During my campaign," he said, “that whole walk across the state was very intense. It was a gimmick, too, I’ll be the first to admit that. “But I stayed at some places and saw some people like these. I was trying to sensitize myself. You know, it’s the easiest thing in the world to forget people like these.” He said he wanted to make sure he didn’t forget them. Lamm went from apartment to apartment with Wade Blank, Atlantis executive director, inspecting the homes and shaking hands with the delighted residents. For most of their lives, the residents have lived in nursing homes, depending on them for medical care and a social life. Barry Rosenberg, a member of the Atlantis board of directors, told Lamm, “So many handicapped are born with a sense of guilt, because they’re different. We’re trying to turn them around and give them some hope. Atlantis residents Blank said, draw on existing city services for medical care and social services.He estimated that it costs $225 a month less, per person, to live at Atlantis than in a nursing home. The city is planning to lower the curbing along the Atlantis boundary on Federal Boulevard, so the wheel-chaired residents easily can cross the street to stores and restaurants. Lamm praised the Atlantis staff as “dedicated people who are trying to make sure a few other fine human beings are cared for."