- KieliAfrikaans Argentina AzÉrbaycanca

á¥áá áá£áá Äesky Ãslenska

áá¶áá¶ááááá à¤à¥à¤à¤à¤£à¥ বাà¦à¦²à¦¾

தமிழ௠à²à²¨à³à²¨à²¡ ภาษาà¹à¸à¸¢

ä¸æ (ç¹é«) ä¸æ (é¦æ¸¯) Bahasa Indonesia

Brasil Brezhoneg CatalÃ

ç®ä½ä¸æ Dansk Deutsch

Dhivehi English English

English Español Esperanto

Estonian Finnish Français

Français Gaeilge Galego

Hrvatski Italiano Îλληνικά

íêµì´ LatvieÅ¡u Lëtzebuergesch

Lietuviu Magyar Malay

Nederlands Norwegian nynorsk Norwegian

Polski Português RomânÄ

Slovenšcina Slovensky Srpski

Svenska Türkçe Tiếng Viá»t

Ù¾Ø§Ø±Ø³Û æ¥æ¬èª ÐÑлгаÑÑки

ÐакедонÑки Ðонгол Ð ÑÑÑкий

СÑпÑки УкÑаÑнÑÑка ×¢×ר×ת

اÙعربÙØ© اÙعربÙØ©

Etusivu / Albumit / Tunnisteet Mike Auberger + Atlantis Community

+ Atlantis Community 6

6

Luontipäivä / 2013 / Heinäkuu

ADAPT (1764)

ADAPT (1764)

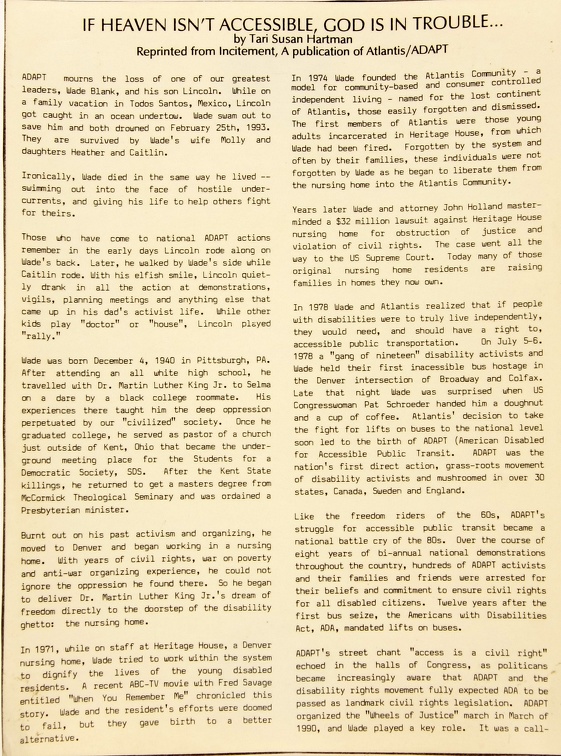

IF HEAVEN ISN'T ACCESSIBLE, GOD IS IN TROUBLE by Tari Susan Hartman Reprinted from Incitement, A publication of Atlantis/ADAPT [This article appears in ADAPT 1764 & 1773 but is completely included here for easier reading.] ADAPT mourns the loss of one of our greatest leaders, Wade Blank, and his son Lincoln. while on a family vacation in Todos Santos, Mexico, Lincoln got caught in an ocean undertow. Wade swam out to save him and both drowned on February 25th, 1993. They are survived by Wade's wife Molly and daughters Heather and Caitlin. Ironically, Wade died in the same way he lived swimming out into the face of hostile under currents, and giving his life to help others fight for theirs, Those who have come to national ADAPT actions remember in the early days Lincoln rode along on Wade's back. Later, he walked by wade's side while Caitlin rode. with his elfish smile, Lincoln quietly drank in all the action at demonstrations, vigils, planning meetings and anything else that came up in his dad's activist life. while other kids play "doctor" or "house", Lincoln played "rally." Wade was born December 4, 1940 in Pittsburgh, PA. After attending an all white high school, he travelled with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Selma on a dare by a black college roommate. His experiences there taught him the deep oppression perpetuated by our "civilized" society. Once he graduated college, he served as pastor of a church just outside of Kent, Ohio that became the underground meeting place for the Students for a Democratic Society, SDS. After the Kent State killings, he returned to get a masters degree from McCormick Theological Seminary and was ordained a Presbyterian minister. Burnt out on his past activism and organizing, he moved to Denver and began working in a nursing home. with years of civil rights, war on poverty and antiwar organizing experience, he could not ignore the oppression he found there. So he began to deliver Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream of freedom directly to the doorstep of the disability ghetto: the nursing home. In 1971, while on staff at Heritage House, a Denver nursing home, Wade tried to work within the system to dignify the lives of the young disabled residents. A recent ABC—TV movie with Fred Savage entitled "When You Remember Me" chronicled this story. Wade and the resident's efforts were doomed to fail, but they gave birth to a better alternative. In 1974 Wade founded the Atlantis Community a model for community-based and consumer controlled independent living center named for the lost continent of Atlantis, those easily forgotten and dismissed. The first members of Atlantis were those young adults incarcerated in Heritage House, from which Wade had been fired. Forgotten by the system and often by their families, these individuals were not forgotten by Wade as he began to liberate them from the nursing home into the Atlantis Community. Years later Wade and attorney John Holland masterminded a $32 million lawsuit against Heritage House nursing home for obstruction of justice and violation of civil rights. The case went all the way to the US Supreme Court. Today many of those original nursing home residents are raising families in homes they now own. In 1978 Wade and Atlantis realized that if people with disabilities were to truly live independently, they would need, and should have a right to, accessible public transportation. On July 5-6. 1978 a "gang of nineteen" disability activists and Wade held their first inaccessible bus hostage in the Denver intersection of Broadway and Colfax. Late that night Wade was surprised when US Congresswoman Pat Schroeder handed him a doughnut and a cup of coffee. Atlantis‘ decision to take the fight for lifts on buses to the national level soon led to the birth of ADAPT (American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit. ADAPT was the nation's first direct action, grass-roots movement of disability activists and mushroomed in over 30 states, Canada, Sweden and England. Like the freedom riders of the 60s, ADAPT's struggle for accessible public transit became a national battle cry of the 80s. Over the course of eight years of biannual national demonstrations throughout the country, hundreds of ADAPT activists and their families and friends were arrested for their beliefs and commitment to ensure civil rights for all disabled citizens. Twelve years after the first bus seize, the Americans with Disabilities Act, ADA, mandated lifts on buses. ADAPT's street chant "access is a civil right" echoed in the halls of Congress, as politicians became increasingly aware that ADAPT and the disability rights movement fully expected ADA to be passed as landmark civil rights legislation. ADAPT organized the "wheels of Justice" march in March of 1990, and Wade played a key role. It was a call-- to— action that galvanized the disability rights movement to demand swift passage of ADA with no weakening amendments. Over 1,000 disability rights activists from across the nation joined forces with ADAPT to demonstrate to the world that they were to be taken seriously. On the second anniversary of the signing of the ADA (July 25, 1992), the city of Denver and its Regional Transit District commemorated that historic event by dedicating a plaque to Atlantis/ADAPT and the "gang of nineteen" who held the first bus. Wade refused to have his name engraved on the plaque, but his silent tears at the dedication ceremony revealed the depth with which he felt the issues of disability rights. He had left his mark forever etched in the foundation of our civil rights movement. In 1990, when it was clear that ADAPT had successfully led and won the fight for accessible public transportation with the passage of the ADA, wade and other national ADAPT leaders convened to plot their next course of action. There was little question for anyone what that next issue would be. ADAPT transformed its mission and became "American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today." Together, ADAPT and wade returned to the scene of one of society's most heinous crimes the warehousing of 1.6 million disabled men, women and children. These disabled Americans committed no crime, yet were and still are, interred against their will, in nursing homes, state schools and other institutions. They are used as the crop of industries like the nursing home lobby, physicians and their conglomerate owners who continue to get rich by robbing our people of their fundamental civil, human and inalienable rights to life liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Most of us are spectators sitting on the sidelines of life, learning history from books. Wade, was an active participant in over three decades of political organizing. He taught others how to create and record their own destiny. A brilliant strategist, he helped shape the tide of the disability rights movement. Yet Wade was never too busy to roll up his sleeves and assist someone with attendant services, push or repair a chair or drive a van. He stood up for what he believed in and expected others to do the same. In his Pursuit to free others from the chains of oppressions he was arrested 15 times and proud of it! Several weeks ago Wade Blank's story, including the development of Atlantis and ADAPT, was officially accepted into the National Archives. Wade, a passionate Cleveland Browns fan, was a loving husband, daddy, friend, organizer and leader. He valued and encouraged the unique contributions that each of us has to give to ourselves, each other and the world around us. We honor his contribution, value his friendship, and grieve the loss of our beloved friend and colleague. Wade was one of the few non disabled allies of the disability rights movement who understood the politics of oppression. At times through the years, his leadership role was questioned, but he never lost sight of the vision, nor lacked the support of those he was close with. Photo by Tom Olin: Wade Blank and Mike Auberger sitting on either side of the plaque honoring the Gang of 19. Caption reads: Co-Directors Wade Blank and Mike Auberger reflect on the past decade of organizing and activism. ADAPT (161)

ADAPT (161)

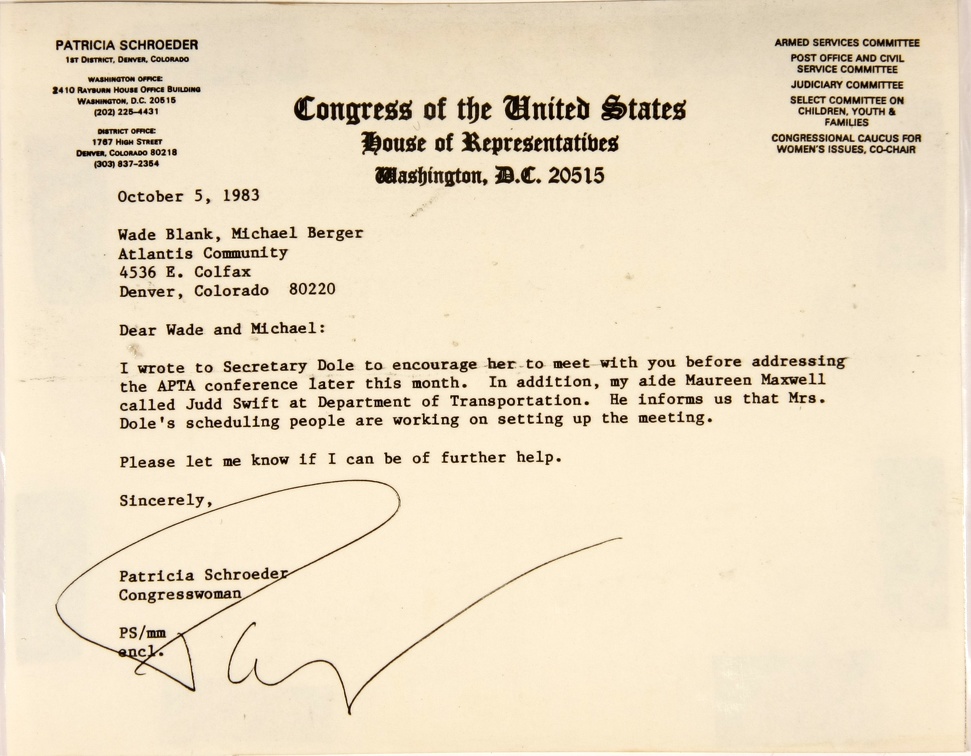

Patricia Schroeder, 1st District, Denver, Colorado Washington Office: 2410 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, D.C. 20515 (202) 225-4431 District Office: 1767 High Street, Denver, Colorado 80218 (303) 837-23 Armed Services Committee Post Office and Civil Service Committee Judiciary Committee Select Committee on Children, Youth and Families Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, Co-Chair Congress of the United States House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 October 5, 1983 Wade Blank, Michael Berger [sic] Atlantis Community 4536 E. Colfax Denver, Colorado 80220 Dear Wade and Michael: I wrote to Secretary Dole to encourage her to meet with you before addressing the APTA conference later this month. In addition, my aide Maureen Maxwell called Judd Swift at Department of Transportation. He informs us that Mrs. Dole’s scheduling people are working on setting up the meeting. Please let me know if I can be of further help. Sincerely, Patricia Schroeder, Congresswoman PS/mm Encl.![ADAPT (154) (4752 vierailua) [Headline] 7 Arrested as Handicapped Protest at Fast-Food Outlet

By Jim Kirksey

Denver Post Staff ... ADAPT (154)](_data/i/upload/2015/11/23/20151123160647-efe71187-la.jpg) ADAPT (154)

ADAPT (154)

[Headline] 7 Arrested as Handicapped Protest at Fast-Food Outlet By Jim Kirksey Denver Post Staff Writer Denver police arrested seven persons – six of them handicapped – during a demonstration at a near-downtown Denver McDonald’s Restaurant Thursday. Wheelchair-bound demonstrators from Denver’s Atlantis Community Inc., which represents disabled people in the area, blocked entrances to the parking lot at the McDonald’s at East Colfax Avenue and Pennsylvania Street beginning about 11:0 a.m. to protest the lack of access to the restaurant for the handicapped. All of the arrests were based on traffic-obstruction charges. Police estimated there were about 20 demonstrators, but leaders of the demonstration estimated the number at 30 to 50. Richard Male, an organizer with the Community Resource Center, said the protesters want three things: access for the disabled to McDonald’s current restaurants, such access to be constructed at all new McDonald’s restaurants, and for the fast-food company to advertise its welcome and accessibility to the disabled. Joe Carle, 45, a community organizer at the Atlantis Community and one of the leaders of Thursday’s demonstration, said the point at issue is what he termed McDonald’s failure to live up to agreements made by the company in negotiations last month. He said McDonald’s officials met in Denver with members of the Access Institute, a national organization for the handicapped with which Atlantis is affiliated, following similar demonstrations at two McDonald’s restaurants in Denver in May. Organizers said McDonald’s agreed at that time to a June 19 meeting in Denver with a negotiating team from the institute. Carle said McDonald’s agreed to pay the costs of the Access Institute negotiators to return to Denver and to send a restaurant official with the authority to make an agreement. Now, according to the leaders of the local disabled group, McDonald’s says it won’t pay the transportation costs of the group’s members and won’t confirm that a representative with the authority to make an access agreement with the group will attend the meeting. The manager at the restaurant refused comment and a corporate spokesman for McDonald’s in Chicago didn’t return a telephone call to comment on the demonstration and the allegations. Sgt. Roy Clem of the Denver police said those demonstrators who were arrested had refused to get out of East Colfax Avenue, and they were arrested for obstruction of traffic. The one non-disabled person was arrested when she jumped in front of a car to block its path in support of the demonstration, Clem said. Detective George Masciotro identified those arrested as: Lori Eastwood, 26, of 1222 Pennsylvania St., who isn’t disabled; Donna Smith, 32, of 236 S. Elliot St.; Robert W. Conrad Jr., 35, of 750 Know Court; George Roberts, 36, of 1255 Galapago St.; Lawrence Ruiz, 30, also of 1255 Galapago St.; Terri Fowler, 28, of 3202 W. Gill Place; and Michael William Auberger, 29, of 1140 Colorado Blvd. Masciotro said they were booked into jail, then released on personal recognizance bonds. ADAPT (618)

ADAPT (618)

November 1992 Access USA News Page 5 Atlantis leads to ADAPT leads to independence Cathy Seabaugh, Staff Writer DENVER,CO-Their offices are relatively small compared to the massive projects the American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today organization tackles. An inconspicuous location in south central Denver serves as national headquarters for the 29 states who have ADAPT chapters. This Colorado town is a gold mine for members of the disabled community, not so much for its accessibility and attitudes, but for the brainstem which this office at 12 Broadway has become. ADAPT representatives throughout the United States act as nerve endings, sending vital messages to the Denver office so it can operate efficiently and effectively. Effectiveness: a term well defined by ADAPT members. ADAPT was conceived and delivered by staff and volunteers of Atlantis Community, founded in 1975 by former nursing home employee Wade Blank and Mike Auberger, a quadriplegic from a bobsledding accident in 1971. Atlantis emerged so that individuals, even those who are severely, multiply-disabled, have the option to live outside an institution. ln its first l5 years, Atlantis was able to successfully transition more than 400 disabled adults from “sheltered settings" to more independent living standards. As an admirable offspring of Atlantis, ADAPT set its own agenda in June 1983 and embarked on an action-packed mission to make public transportation accessible to everyone. American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit set out to train, develop and empower disabled activists so they could effectively battle for that accessibility. Eighteen members of the Atlantis community had taken the first strides toward accessible public transportation in Denver when they gathered on July 5&6, 1978, to block city buses at Broadway and Colfax across from the state capitol. ‘Then in 1982, after beating up the board enough," said Auberger, one of the 18, "they decided they'd buy all lift-equipped buses." Once ADAPT formed the next year, the foundation was in place. With Denver as a model, activists began chipping away at other cities’ granite-like, antiquated public transportation systems. "(Former President Jimmy) Carter appointed Brock Adams in 1976 and Adams set a federal mandate that all new buses bought with federal money had to have (wheelchair) lifts,” Auberger said. "Under the Reagan administration, APTA (American Public Transit Association) sued (to avoid the lift requirements) and won. "APTA was having its national convention in Denver in October 1983 and about 20 people from across the country showed up to join about 22 people from Denver. We sent notice to (APTA) that their convention would not go uninterrupted if they did not meet with us. They went to the mayor, but he said he wouldn't protect them unless they agreed to meet with us.” ADAPT met APTA there. They would meet many more times. "We decided wherever they had a convention, we would go,” Auberger said. "It moved us around to communities where they'd never been exposed to the issues. People all of a sudden became aware. "If we're talking about the issues, people are going to form an opinion. You polarize people. Whether they support you or not is not the point. If there's not an opinion there, you can't change it." The deep roots, pockets or whatever of APTA were a long-time barrier for ADAPT. But as the Americans with Disabilities Act cemented and included regulations for public transportation, APTA’s resistance to ADAPT's demands weakened until the federal govemment finally made ADA the law. With that priceless piece of legislation signed and inducted into the pages of history, ADAPT was ready for its next mission. "What we said at that point to members was to put out feelers in your communities,” Auberger said. "What we found was personal assistants was the biggest issue of concern.” Retaining the ADAPT acronym, the group devised new plans to force change in the long-term health care system of the United States. “At least 60 percent of ADAPT members have (resided) in nursing homes at one time or another,” Auberger said, "The other 40 percent have spent their lives trying to avoid going into one.” Although ADAPT and Atlantis are neither to lose its identity in the other, they are a family unit and work together toward change. Atlantis is a certified home health care agency, making 53,000 visits each year in Denver and Colorado Springs, serving approximately 85 clients. “That's 365 days a year, whether there's three feet of snow on the ground or it's 105 degrees," Auberger said. “We have a 24-hours-a-day emergency backup system that works probably 98 percent of the time." One Atlantis client is a C2 quadriplegic who is on a ventilator nonstop. Yet he is allowed to live in his own home with the help of Atlantis personal attendants. "That shows you our capabilities,” Auberger said. ”We can provide 24-hour care for about $7,500 a year. A nursing home would do it for $20,000.” ADAPT’s scrapbook for the past two years includes protests in almost countless cities throughout the country. Wherever Dr. Louis Sullivan, Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, made a speech or appearance, ADAPT added itself to the invitation list. The protests usually involved arrests, which is a proven effective tool for drawing media coverage. Radical activity, some say. "We really give the middle-of-the-road disabled community members the power to make change," Auberger said. "We make them look sane. “It's like in Illinois, Gov. Edgar didn't have a problem meeting with the straight group who went to Springfield because they were sane. lf he dealt with our radical group, he'd have to deal with all radical groups. We really give (middle-of-the-road community members) a platform." ADAPT picks on Sullivan because, they say, he can initiate change. They argue that Sullivan's signature is all that's necessary to require the states receiving Medicaid to provide personal assistants. Just more than half the states provide such funding and many; if not all, of those programs are underfunded, restricted and far short of meeting the demand. ADAPT seeks to convince Health and Human Services - Sullivan - to take one-third of the $15 billion Medicaid dollars and commit it to home-based, consumer-controlled services. "Every state that buys into Medicaid has to fund nursing homes,” Auberger said, explaining how the system currently works. Sixty-five percent of all money paid to nursing homes is Medicaid funds. "States have little play in what they can do with Medicaid.” Nursing homes use what's called a “cold bed rate" which refers to the empty beds in their institutions that are not producing income. Lobbyists for the nursing home industry are looking at these rates and profit margins, not at long-term care that allows individuals to retain their independence. "We’ve become a valuable commodity,” Auberger said. "It's a normal mindset to put someone in a nursing home. This is so ingrained in our society. There's currently no alternative, and most people aren't able to envision the type of care we're talking about." Auberger encourages every person he can to write letters to members of Congress, senators and other politicians who can have an impact on the future of people with disabilities. "When you do that, you raise a level of consciousness,” he said. "You don't have to mention (the numbers), just the concept. "The logic is the problem. When parents are doing (personal attendant care), for free, it doesn't have to be skilled. When Medicaid pays for that same care, a nurse has to do it.” Statistics provided by the American Health Care Association show the average lifespan on an individual in a nursing home is 21 months. "You can't convince me there's quality care in a nursing home," Auberger said. "We (at Atlantis) are non-medical personal attendants. When the staff goes into a home, the person in that home is the boss. We do things the way they want us to do them. "People don't have to give up their power to able-bodied people. But it's okay to share the power." Although many members of the disabled community have made endorsements this election year, ADAPT chooses to remain rather neutral - for a change. "Don't pick a side,” Auberger said. "As soon as you pick a side and that side loses, you now have an enemy on the other side. That's been real effective tor us. We'll rate candidates on disability issues, but we won't endorse anyone. "If there's a disability issue in Colorado, legislators call here, the media calls here. We're a powerful entity in this state. As hundreds of ADAPT activists confronted the annual conference of the nursing home industry in San Francisco October 19-21, the power of this entity spread toward the Pacific. Persons interested in more information about ADAPT can call Auberger or Wade Blank at (303) 733-9324 (voice and TDD). INSERT AT CENTER OF PAGE: Across the top in bold letters the word "ATLANTIS" and below that ADAPT's new Free Our People logo, the wheelchair access symbol with it's arms raised above its head breaking chains that are bound to it's wrists. Above this figure, in a semi-circular pattern the words "Free Our People" and below, also in a semi-circular pattern, "ADAPT"![ADAPT (143) (3047 vierailua, arvostelupisteet 4.37) Rocky Mountain News

[Headline] Changes at two-story McDonald’s satisfy activists

By: Jay Croft... ADAPT (143)](_data/i/upload/2015/11/23/20151123160116-086b1213-la.jpg) ADAPT (143)

ADAPT (143)

Rocky Mountain News [Headline] Changes at two-story McDonald’s satisfy activists By: Jay Croft, Rocky Mountain News Staff writer Handicapped-rights activists claimed a victory Tuesday in McDonald’s construction of a 750,000, wheelchair accessible hamburger restaurant in Capitol Hill even though company officials said protests weren’t responsible for building the one-of-a kind facility. The restaurant opens at 11 a.m. Saturday. Representatives of Atlantis Community, who last year led protests at the East Colfax Avenue in Pennsylvania Street restaurant, said they are satisfied with the changes. “It’s fantastic,” said Mike Auberger, Atlantis community organizer. “Apparently what we did had some kind of effect.” But officials at McDonald’s, the nation’s largest hamburger franchise, said they tore down the old restaurant because it was “in need of a tremendous amount of repairs,” not because it was inaccessible to handicapped people. Kitchen equipment, air conditioning and drive-through facilities were outdated, said Jim Clark construction engineer. He said the restaurant was 18 years old. Auberger and Clark said the restaurant meets city requirements for handicapped accessibility, which include wheelchair ramps, special parking spaces and access to restrooms. McDonald's also made some tables wheelchair-accessible. Other McDonald's restaurants under construction in the Denver area are scheduled to be accessible also, Auberger said. "They've gone out of their way to prove their point in this city at least." Clark said cost of construction was $750,000. The new two-story McDonald's, with an upstairs atrium and a seating capacity of 200, is “one of a kind” Clark said. “It’s more of a high-rise office design (than other McDonald’s).” It will employ about 100 people, including many of the 70 employees from the old restaurant who want to return, Clark said. Debbie Van Gundy, a six-year employee, will continue as manager. “I love it,” she said. “It’s a great improvement to have a whole new store and equipment.” A “human ribbon” will surround the building, along with 500 $1-bills, said Gary Peck, operations consultant. The money will go to Ronald McDonald House, a home for the families of cancer patients in Children’s Hospital. The opening coincides with the 30th anniversary of McDonald’s in Denver region, which includes Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Wyoming, Peck said. McDonald’s will host an invitation-only part Thursday night. Auberger said Tuesday no one at his office had been invited.. “We’re not exactly friends,” he said. “It’s a comfortable agreement and that’s about all.” ADAPT (122)

ADAPT (122)

Denver Post [This article continues on in ADAPT 123, but the entire text is included here for easier reading.] Photo by Lyn Alweis: A short haired man in a jacket and dark slacks [Mel Conrardy] is lifted in his wheelchair from the sidewalk to a bus. The lift comes out of the front door of the bus and has railings on either side of the lift almost as tall as the seated man. Just by the bus door is a sign on the side of the bus that says "RTD Welcome Aboard." Caption: An RTD bus with wheelchair lift provides mobility for Mel Conrardy Title: Leaders of handicapped rate RTD service best in country By Norm Udevitz, Denver Post Staff Writer Disabled Denverites just a few years ago had as much chance of riding a bus as they did of climbing Mount Everest. “It was brutal the way RTD treated us,” said Mike Auberger, an official in the Atlantis Community, for the disabled and a leader in the fight that has turned the Regional Transportation District’s handicapped service around. In the 1970s and early 1980s, RTD busses then rarely equipped with wheelchair lifts, often left wheelchair-bound riders stranded on streets. Drivers, lacking training in dealing with visually or language impaired people, panicked when blind or deaf riders tried to board buses. “It used to be that even in the dead of winter, when it was below zero, those of us in wheelchairs would wait 2 or 3 hours for a bus to finally stop," Auberger recalls. “And often the lift was broken and we couldn't get on the bus anyway. And usually the drivers were rude and angry. They would tell us that we were ruining their schedules." But conditions have changed, Auberger says: “Right now, Denver has the most accessible public transit system for the handicapped — and all the public - in the country." Debbie Ellis, a state social services worker who heads the agency's Handicapped Advisory Council, agrees, saying: “It took a lot of pressure, but RTD has responded and now the bus system is doing a good job of serving the handicapped." Leaders of national programs for the disabled also agree. In fact, the President's Committee on Employment of the Handicapped will bring 5,000 delegates, many of them handicapped, to its national conference in Denver in April. This will be the first time in four decades the group has held its national session outside of Washington DC. “One of the key reasons we're meeting in Denver this year is because it just might be the most comfortable city in the country for the handicapped,” says Sharon Milcrut, head of the Colorado Coalition for Persons with Disabilities, which is hosting the conference. “A very important aspect of that comfort," she notes, “is how accessible the transit system is for the handicapped.” It didn't get that way easily. In the decade between 1974 and 1984, handicapped activists had to pressure indifferent RTD administrators and directors. Each gain was hard won. “We used every tactic in the book, from lawsuits to bus blockades on the street and sit-ins at the RTD offices," says Wade Blank, an Atlantis group director. “The lawsuits didn't help much but when we took to the streets in the late 1970s, I think that's when we started getting their attention." Blank and others also say the 1984 hiring of Ed Colby as RTD general manager helped. Before he arrived, less than half of the 750 RTD buses had wheelchair lifts, which often were in disrepair. Training for drivers to learn how to deal with handicapped riders was minimal. Agency directors resisted change. RTD relied heavily on a costly special van operation called Handyride - a door-to-door pickup service for handicapped. It has cost $13[? glare makes number hard to read] million to run since it began in 1975. “Over the past couple of years the turnaround has been phenomenal," Auberger says. “All of RTD's new buses are being ordered with lifts and older buses are being retrofitted." By 1986's end, almost 80 percent of the bus fleet — 608 of 765 buses — had wheelchair lifts; 82 percent of the fleet's 6,242 daily trips are now accessible for the disabled. Plans call for the fleet to be 100 percent lift-equipped by 1987's end. “The lifts aren't breaking down all the time now, either," Auberger said, noting that agency officials found drivers had neglected to report broken lifts: “That way the lifts stayed broken and drivers had an excuse for not picking us up. A bunch of people were fired over that and others realized that Colby wasn't kidding about improving handicapped service." Driver training also has improved dramatically. “It isn't perfect yet,” Ellis of the advisory council says. "But everyone is working hard at it. What we are finding is that 20 percent of the drivers understand that they are moving people, all kinds of people, and they're really great with the handicapped. “Another 20 percent figure their job is to move buses and to heck with passengers, all kinds of passengers. That bottom 20 percent probably won't ever change. So we're working real hard on the 60 percent in between," Ellis says. Drivers, for example, learn to help blind riders. “That’s an improvement that helps the disabled, but it also helps regular passengers who are newcomers to the city,” Ellis says. All the improvements haven't come cheap. Since 1974, more than $5million has been spent on lifts and lift maintenance, most of the expense was incurred in the last three years. RTD plans to spend $9 million more in the next six years to keep the fleet up to its current standards and pay for more driver training. Another $4 million will be spent on HandyRide service. Ironically, Auberger and Ellis both say one of the biggest problems remaining is getting more handicapped people to use mass transit. “There are no reliable figures," Ellis says. “But we think there are about 20,000 handicapped people in the metro area and only about 200 or 300 are using buses on a regular basis." Auberger, confined to a wheelchair after breaking his neck in an accident ll years ago, complains: “The medical system builds a bubble around handicapped people and makes them think they have to be protected. "That's just not true in most cases. So one of the things we're doing now is educating the handicapped to overcome their fears. We've finally got a bus system that works for us and we want the disabled to use it." Photo by Lyn Alweis: A rather straight looking man [Mel Conrardy] in a white jacket, big mittens, and a motorized wheelchair, wears a slight smile as he rides the bus. Someone in a dark jacket stands beside him, and behind him, further back on the bus, other riders are sitting on the bus seats. Caption reads: A bus seat folds up to anchor Mel Conrardy's wheelchair to the floor. Conrardy commutes to work at the Atlantis Community.